Is drug addiction on the rise in Mexico?

Untangling the data on drug use, dependence and overdoses

Welcome to The Mexpatriate.

In today’s edition, I take a look at the latest official statistics on drug use in Mexico and what they reveal (or not) about the panorama of addiction in the country.

If you haven’t checked it out yet, be sure to watch or listen to the latest episode of The Mexpat Interview, a conversation with journalist Sam Quinones about how synthetic illicit drugs have transformed addiction and trafficking.

Not getting high on the supply

Mexico has been the throughway for every drug on its journey to the United States—from marijuana to cocaine to fentanyl and meth—for over a century. But the trajectory of drug use and addiction in Mexico has been quite different than north of the border. Even as U.S. demand skyrocketed and the Mexican drug trade boomed in the 1960s and 70s, drug use remained low in Mexico. Under U.S. pressure, the Mexican government adopted increasingly prohibitionist drug policies, which have loosened little since. While recreational cannabis use was decriminalized by the Supreme Court in 2021, it has yet to be fully legalized and commercialized.

Mexico’s low rate of drug use and addiction is sometimes attributed to cultural generalizations—AMLO often credited the strength of Mexican family values—or to alleged restrictions imposed by traffickers on selling their most potent drugs at home (if not for ethical reasons, then for their bottom line). Another factor is simply a dearth of data.

There have been warning signs over the last decade that Mexico’s immunity to widespread drug abuse could be waning. From increased requests for addiction treatment and anecdotal reports of spikes in overdose deaths in border cities like Mexicali and Tijuana, to fentanyl detected in “party” drugs in Mexico City and in medications sold at unregulated pharmacies in beach resorts. However, official monitoring and data collection has been sporadic.

The national survey of drug, tobacco and alcohol consumption (ENCODAT) was skipped during AMLO’s term (one of many victims of austerity), which means that the survey just published in December 2025 was the first in nine years. Let’s take a look at the findings.

Adult use goes up, teen use goes down?

The 2025 ENCODAT showed that 14.6% of adults have tried an illicit drug, up from 10.6% in 2016, however the government focused attention on another data point: in adolescents, this trend went in the opposite direction.

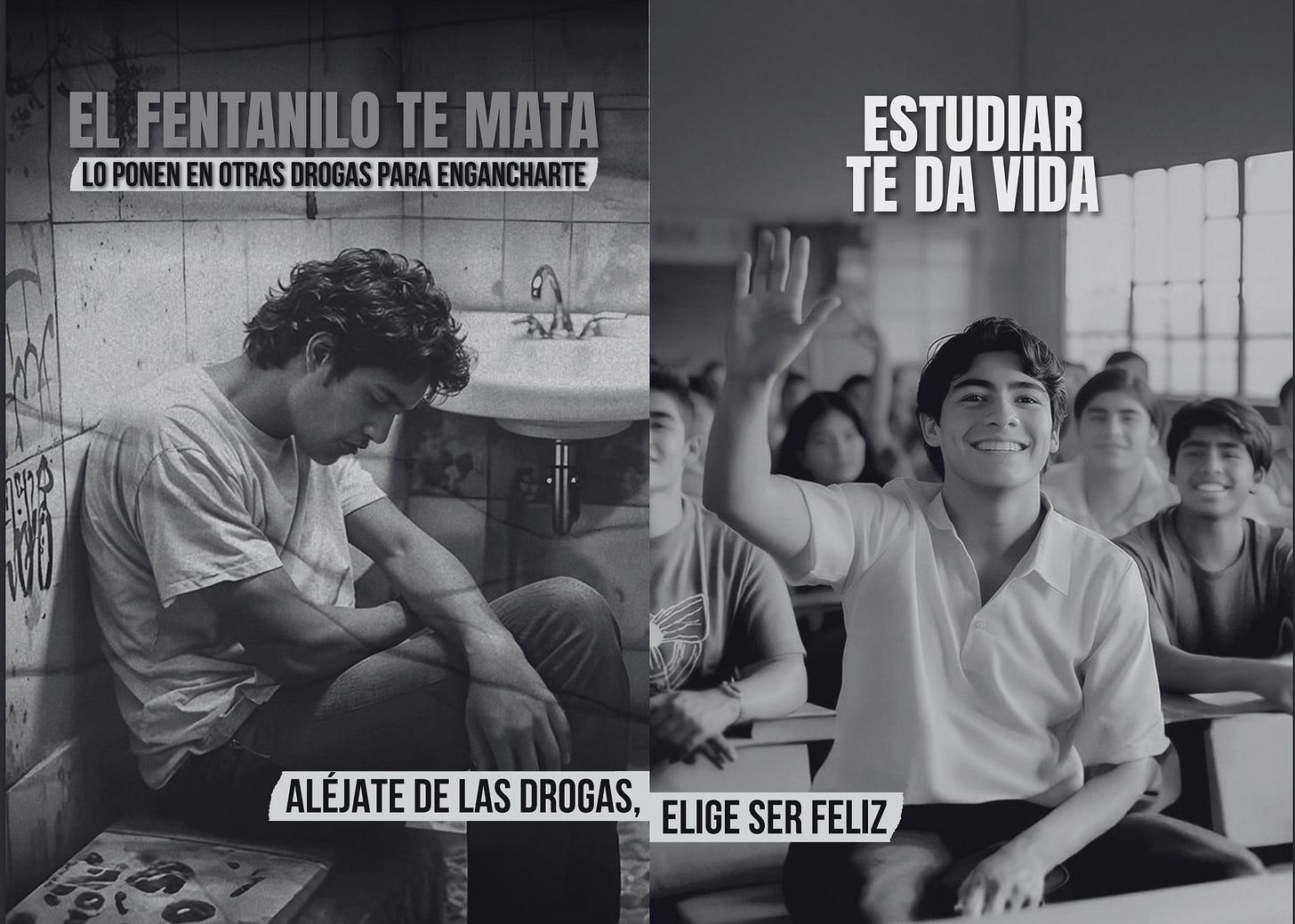

In 2025, 4.1% of 12 to 17 year-olds reported they’d consumed an illegal drug, compared to 6.2% in 2016. President Sheinbaum celebrated this, along with a reported reduction in non-medical fentanyl use (just 0.1% of adults reported using in the last year), as indicators that the government’s “Stay away from drugs: Fentanyl will kill you” campaign is working. The survey reported drug dependence in 0.6% of adults—the same percentage as reported in 2016. Cannabis and cocaine were the top two most-consumed illicit drugs in both 2016 and 2025, but methamphetamines now come in third, surpassing inhalants.

Wet blankets from skeptical experts piled on quickly after the survey was released. One analyst wrote that the survey’s “image of Mexico has more filters on it than a social media photo.”

For example, the survey rather improbably found that the average age for first consuming alcohol is 18.2 years old, while the age for first trying an illegal substance rose from 17.8 in 2016 to 20.1 in 2025. Not only does this belie everyday experience in schools and homes around the country, it contradicts other data collected in national health studies that have found alcohol use in children as young as 10 years old. The results may reveal more about the way the survey was conducted—with parents nearby as minors answered the questions—than reality.

Another criticism leveled at the 2025 ENCODAT is that the sample size is much smaller—from 56,877 respondents in 2016 to just 19,200 in 2025.

Unregulated rehabs and unreported overdoses

The limitations of the ENCODAT mean that we need to look elsewhere to fill in the gaps.

In June 2025, the government published a report on addiction treatment demand that showed some startling statistics. In 2014, only 9.1% of people seeking treatment via private and public rehab centers were hooked on meth, and in 2024 that number surged to 51%. There were only three cases of requests for fentanyl addiction treatment recorded in 2014, but in 2024 there were 465 cases (actually a decrease from a peak of 518 cases in 2023).

In 2023, there were 247 addiction rehabilitation centers registered in the country, but authorities acknowledge that far more unregulated centers exist (as many as 3,000). Many of these are “anexos” where addicts are often involuntarily sent and held—sometimes for years. Anexos are frequently founded by former addicts and serve as the only treatment option for poor families. They have also become notorious as targets for cartel recruitment and violence. The 17 year-old sicario who gunned down Uruapan Mayor Carlos Manzo on Nov. 1 (and was himself executed shortly after) was reported to be a meth addict recruited from a drug rehab center by a Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG) operative.

“One out of every two of our patients is already reporting methamphetamine use,” said Bruno Díaz, director of research for national juvenile addiction treatment in a recent interview. “We might even see in the coming years that methamphetamines become the main illicit drug of consumption.”

Concern about meth addiction is at least on the government’s radar. At the ENCODAT presentation, Sheinbaum said the public service campaign would switch gears to focus more on meth than fentanyl this year.

And what about drug overdose deaths? Official statistics are very low—in 2022, there were 408 reported deaths from illicit drug overdose nationwide, and between 2013 and 2023, just 114 deaths associated with opioid use. However, a study published in the American Journal of Public Health in 2024 found that the incidence of fatal overdoses in Mexico—while still far lower than in the United States—had doubled between 2005 and 2021. They estimated a rate of 0.79 deaths per 100,000 in 2021, which would have put annual fatal overdoses at just over 1,000 cases (there were 32.4 overdose deaths per 100,000 in the U.S. in 2021).

The authors of the study noted that “it is likely that our estimates are a serious underestimation of the true extent of overdose mortality in Mexico” which “stems from the inadequacy of the current overdose surveillance system in Mexico.”

Going deeper: Benjamin T. Smith’s “The Dope” is essential reading on the evolution of the drug trade in Mexico, and if you want to learn more about anexos, check out “The Way That Leads Among the Lost” by Angela Garcia.

If you enjoy The Mexpatriate, please consider supporting my work with a paid subscription or by sharing it! And if you have any feedback, please email me at hola@themexpatriate.com.