The rules of the game

Electoral reform returns to the agenda, plus the Ayotzinapa case turns 11

Welcome to The Mexpatriate.

Eleven years ago tonight, a group of students from the Ayotzinapa rural teaching college traveled to Iguala, Guerrero. They planned to commandeer buses to go to Mexico City and join protests marking the anniversary of the Tlatelolco student massacre of Oct. 2, 1968; instead, Sept. 26, 2014 would become another grim date in the national memory.

The attack on the normalistas (which left six people dead) and subsequent disappearance of 43 of them was a watershed moment for Mexico; a before-and-after event. The outcry it inspired nationally and abroad—even as just one of many atrocities and disappearances in the country— continues to echo over a decade later. And while there have been many arrests and revelations since, only partial remains of three of the students have ever been found.

Parents of the students marched with thousands more in Mexico City today and others marched in cities nationwide; on Thursday, one group of protesters rammed a military base in the capital with a truck and then set it alight (no injuries were reported).

During his campaign and as president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador promised truth and justice for the 43. But by the end of his term, the investigation had stalled yet again (worth reading this report from Ioan Grillo about the role of “El Cuini,” recently expelled to the U.S., as a dubious protected witness).

President Claudia Sheinbaum met with the families earlier this month, and a new special prosecutor, Mauricio Pazarán, was assigned in July—his predecessor was accused of misconduct and made no visible progress on the case.

In tonight’s free letter, I cover President Sheinbaum’s electoral reform plan, which recently started a national tour to get public input.

To support my work and get full access, please consider signing up for a paid subscription.

Back to Plan A?

Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s discourse always had a distinctive flavor and recurrent themes since first emerging in the national conversation: disdain for neoliberalism, passion for national sovereignty and outrage over election fraud (he lost twice before winning the presidency in 2018).

As part of the sweeping counter-reformation agenda of his sexenio, AMLO included an electoral reform, which was thwarted in Congress in 2022. He then pivoted to “Plan B,” modifying legislation below the constitutional level in order to achieve at least some of his goals. This was met with anti-reform protests, known as the “marea rosa” or “pink wave” because of the adoption of the color used by the National Electoral Institute (INE); later, the Supreme Court threw out the Plan B reform. Which brings us to “Plan C”: a decisive victory for Morena at the ballot box in 2024 that would allow the party to carry out his constitutional reform gambit.

The judicial reform was the first to make it through with Morena’s supermajority in Congress in September 2024; not long after the fraught judicial elections on June 1 of this year, Sheinbaum mentioned that electoral reform was also still on the horizon.

Phase one of Sheinbaum’s process launched with the establishment of a presidential commission under the leadership of Pablo Gómez. A long-time insider in national leftist politics—he was a political prisoner during the 1968 student movement—Gómez previously led the Financial Intelligence Unit (he stepped down about six weeks after the U.S. government’s money laundering allegations against three Mexican financial institutions).

Gómez was also one of the architects of AMLO’s original electoral reform, inspired by the president’s signature policy formula: austerity, popular election of officials and centralization. The reform proposed cutting expenditure on elections and funding for political parties, the direct election of INE councilors, and the elimination of proportional representation seats (“plurinominales”) in federal Congress—who make up 200 of 500 deputies in the lower house, and 32 of 128 senators.

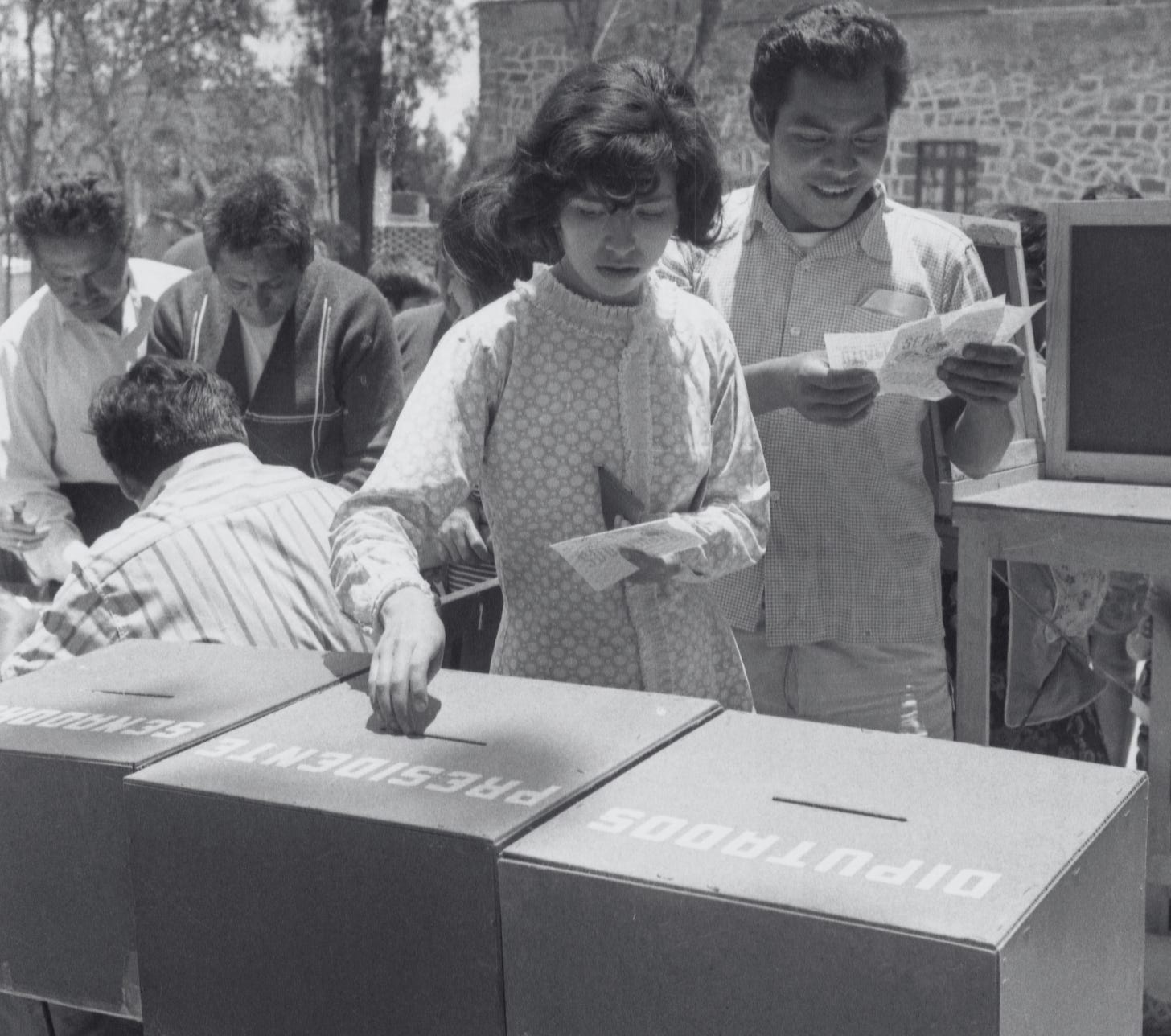

Mexico’s young democracy has had a love-hate relationship with pluris. In 1977, the administration of President José López Portillo promoted an electoral reform that at first glance seemed contradictory to the goals of the PRI; by confirming the constitutional status of political parties and formalizing proportional representation, more opposition parties were able to gain a foothold in Congress as plurinominales in the elections of 1979. In fact, Pablo Gómez himself served as a deputy for the Communist Party.

Why did the PRI open itself to possible electoral losses? As a former INE official, Javier Santiago Castillo, explains:

“It wasn’t strictly a gracious, democratic concession, but rather one with double intent: to give the opposition a space, while also ensuring that it would not aspire to win a relative majority.”

This consolidation of the opposition cracked the foundation of PRI hegemony, but the pluris would also become synonymous with dirty politics; selected using party-generated lists, they are prone to abuse as political favors. AMLO was not the first to take aim at these representatives—Felipe Calderón (PAN) and Enrique Peña Nieto (PRI) both attempted to reduce their numbers, though not to eliminate them entirely.

While the satellite parties in the Morena coalition—the PVEM (Green Party) and the PT (Labor Party)—have helped the ruling party push its constitutional reforms through Congress, they may be less compliant with this reform.

“...If they get rid of proportional representation of minorities, then those parties would be doomed to lose, to disappear,” said José Woldenburg, former head of the national electoral agency, in a recent interview about the reform.

A PVEM senator from Chiapas, Luis Melgar Bravo, said in a recent interview in Reforma that “we are definitely not in agreement about plurinominales” and groused that “if they [Morena] don’t allow us to be competitive, well then that’s not an alliance.”

The PVEM party president, Manuel Velasco, has expressed support for Sheinbaum’s proposal to reduce funding for political parties—but only if applied equally to all of them. Mexico’s political parties receive the bulk of their financing from public coffers, with 30% of the budget allotted equally to the six registered parties, and the remainder divided proportionally based on the votes received in the most recent elections.

Sheinbaum has insisted that all voices will be heard and proposals considered before her bill goes to Congress next year; but she’s stocked her commission with friendly faces. The six members who join Gómez are all currently serving in Sheinbaum’s cabinet—including Rosa Icela Rodríguez (secretary of the interior), José Peña Merino (the ubiquitous head of the Digital Transformation and Telecommunications Agency) and ex-Supreme Court Chief Justice Arturo Zaldívar (general coordinator of politics and governance for the executive office).

Sheinbaum has said that the public forums take the reform out of the opaque upper echelons of the parties and bring it to The People.

“What’s important is that all viewpoints are heard and that society gets involved in designing the rules of the democratic game,” said Gómez in a press conference on Monday.

But how many will show up to these forums? The last great call to democratic duty, to elect the nation’s judiciary, got a paltry 13% of Mexican voters to participate. Polls indicate that about half of Mexicans are satisfied with how their democracy functions, but as Morena pushes for more elections and referendums, they might also be starting to suffer from chronic democracy fatigue syndrome.

After all, while the mechanics of democracy are vitally important, they can also seem far removed from daily life—and dismally boring. Gerrymandering and campaign finance periodically rile up voters in the U.S., but these issues tend to fade quickly into the background when hot-button topics like crime, the economy and who’s getting a Golden Visa (or getting shut down on late-night TV) steal the headlines.

*CORRECTION (Sept. 27): An earlier version of this article described Arturo Zaldívar as a close ally of President Sheinbaum rather than a cabinet member. In fact, he is part of the president’s extended cabinet.

Questions, criticism or tips? Email me: hola@themexpatriate.com. And if you like what you’re reading, be sure to subscribe below.

Thank you for giving us a CLEAR Vision of what has happened with no bias. God, bless you take care of yourself.