Entre Semana: Trust issues

On natural and human disasters

Welcome (finally) to a Wednesday edition of The Mexpatriate.

The global discourse has changed in tone since my last post, hurtling towards new lows of nihilism and cruelty. The collision of brutal violence in Israel and Gaza with the immediacy of the internet makes it feel like the whole world is caught up in a wartime propaganda battle—in real time, everywhere you look online. As thousands die, many observers far away from the conflict find it necessary to condemn others’ condemnations (or lack of them), to lob accusations of genocide like grenades, to demand censorship. It fills me with sickening despair. But I recognize my despair is not relevant.

Aiding and abetting this sense of disorder, of fragmented allegiances and ethical horrors, is the rapid depletion of trust: in what we hear, what we see, what we read, what we know.

We have seen this decline coming, but the pace is quickening—we are apparently sprinting towards a singularity of stupidity.

The paradox of our age is that we eat, breathe and sleep information, seem unable to fathom surviving in an atmosphere without it, but as dizzyingly evidenced by recent events, there is a problem: we struggle to believe any of it. And even less when the stakes are high.

In the face of inundation, our primate brain seeks something to hold on to - something to trust. Your instinct is to decide a priori how to categorize the endless inputs.

Ideology is a single story, told a hundred different ways: you already know the ending, and what a relief it is.

So whether it’s the conflict in Ukraine, or blood spilled in Gaza, or a natural disaster, or a politician’s claims, you have your answers ready—before you allow yourself to ask questions.

From the archive:

La Semana: Oct. 17, 2022: The week in the “Guacamaya” hacking revelations and my thoughts on paradox

Hurricane Otis and the politics of disasters

“The pain of destruction creates fleeting heroes, but above all—villains. Our fears, frustrations and grievances must be unloaded on something or someone.”

Jorge Zepeda Patterson

Hurricane Otis, which made landfall a week ago, is a devastating tragedy for Acapulco and other affected areas in Guerrero. As of today, 46 people are dead and 58 missing (official count), and this number is certain to rise. Millions have been affected – 80% of hotels were damaged in the historic port city.

Someone must be to blame.

Otis descended on Acapulco (population over 1 million in metro area) as a Category 5 storm (the only recorded northeastern Pacific hurricane to make landfall at this intensity) with little warning, doubling in strength in 12 hours. Communication was lost after impact—every electric utility pole in the city was leveled.

As the gravity of Otis spread in the news, the story of the storm’s unexpected impact was joined by another narrative: the government was woefully under-prepared for this disaster, leaving the country at grave risk for future disasters caused by climate change.

Disaster preparedness is a tricky thing, no doubt. Mexico should know.

In 2010, the National Disaster Prevention Center (Cenapred) calculated that 31.1 million Mexicans (across 41% of national territory) were exposed to risk from storms, hurricanes and floods, and that 31 million were exposed to earthquake risk. The U.N. has categorized Mexico as one of 30 countries at risk of suffering three or more large-scale disasters per year.

This particular storm was an outlier, intensifying at an unprecedented pace, bewildering meteorologists. “Ten days ago, no one in Mexico, or in the U.S. or in Canada or at the university would have believed we could see such a huge error,” according to UNAM climate scientist Jorge Zavala. There wasn’t time to prepare.

One of the criticisms leveled at AMLO has been that his short-sighted government “austerity” policies, which included eliminating the National Disaster Fund in 2021, left Mexico defenseless.

But is this true? Not exactly.

The National Disaster Fund (Fonden) was created in 1996, and had two sources of funding: a federally-assigned annual budget and a fideicomiso or trust (more coming on trusts below), which was eliminated two years ago, along with 109 other trusts in an initiative pushed by Morena and AMLO. However, Fonden still exists as a federal program, with an available budget of 11 billion pesos this year—though today the president announced a reconstruction plan of 61.3 billion pesos (still far below the estimated damages of $15 billion USD). Mexico also has maintained its CAT (catastrophe) bond via the World Bank, which was first issued in 2006 and most recently, was issued for $485 million USD in 2020. As a Wilson Center article pointed out in 2021:

“Should an event trigger a payout, the money will be transferred to the Mexican treasury rather than the FONDEN trust. Experts say the decision to retain the CAT bond affirms the government’s commitment to disaster risk financing and existing catastrophe bond structure.”

Can we at least blame climate change?

Scientists say warmer waters increase the likelihood of strong hurricanes, but so far they are puzzled by the particular velocity of Otis. While our weather forecasting models have gotten more sophisticated, this is a reminder we can still have major misses.

While the global phenomenon of increased ocean temperatures has been blamed, we are also in a year of El Niño, a weather cycle that has likely existed for thousands of years, causing warming water temperatures and a more severe Pacific hurricane season. El Niño began in June this year and is expected to last through spring 2024.

Interesting to note: there have been only 20 recorded Category 5 Pacific hurricanes since 1959, and 13 of those since 2002. Satellite data on tropical cyclones in the eastern Pacific only go back to the 1970s—precious little time in Earth’s climate history—but this season is looking to be record-breaker, as explained in Yale Climate Connections:

Otis comes only two weeks after Hurricane Lidia hit the Pacific coast of Mexico, about 35 miles south-southwest of Puerto Vallarta, as a Category 4 storm with 140 mph winds. Lidia was also a rapid intensifier, increasing its winds by 65 mph in the 24 hours up to landfall. At the time, Lidia was tied as Mexico’s third-strongest Pacific hurricane on record, so Mexico has now had two of its top-seven landfalling Pacific hurricanes on record this month.

Rebuilding Guerrero will be arduous, considering not only the degree of damage, but also the notorious corruption in the state’s government, lack of infrastructure and rule of law. In fact, just two days before the hurricane hit, the state made headlines (globally) when 13 members of law enforcement were ambushed and murdered in the town of Coyuca Benítez, 32 km from Acapulco. The town was also decimated by Hurricane Otis.

I will be continuing to follow the aftermath and government response in the coming weeks.

If you want to help victims of Hurricane Otis, there are donation centers in cities all over Mexico accepting non-perishable food, medicines and other necessities, as well as fundraisers set up by various banks and La Cruz Roja.

Trust funding fights

There have been a few more episodes aired in the showdown between AMLO and the judiciary. A week ago, the Senate passed a bill (promoted by Morena) that dissolves 13 of 14 federal judiciary trusts – in other words, a budget cut of 15.45 billion pesos. After the bill had passed in the Chamber of Deputies the week before, protests and strikes by court workers popped up around the country, and an estimated 3,000 people marched in Mexico City against the legislation. The president described the protests as “embarrassing” since he insists that the bill will not affect the majority of federal workers, just the excessive “privileges” enjoyed by their superiors.

The script is familiar: AMLO claims the judiciary is corrupt and abuses public funds, and the opposition claims democracy is at stake. In fact, the court workers’ protests look very similar to those against the president’s electoral reform and in defense of another government institution that he has lambasted, the National Electoral Institute (INE).

According to Morena, the monies in the trusts are there for superfluous expenses (such as security, which for judges in Mexico, does not seem frivolous), and according to the Supreme Court, federal judiciary employees, not high-ranking judges, are the “principal beneficiaries of the benefits linked to the trusts.”

Is this budget cut going to affect how the judiciary functions? Will it damage judicial independence? Based on the most recent federal audit (from 2018), it appears these trusts have been accruing public funds for many years, a fraction of which is spent on the operations of the judiciary. In fact, the trusts’ funds have quadrupled in ten years. This is because the federal judiciary is also allotted a standard annual budget by Congress, which is used to pay salaries, benefits and other essential expenses. So, while no explicit misuse of funds is evident, it seems specious for the judiciary to argue their ability to operate will be affected by the reallocation of funds they do not currently use to function.

In a report published by Fundar (a think tank focused on transparency) in 2018 entitled “Trusts in Mexico: The art of making public money disappear”, the researchers document the history of these trusts, which at the time numbered 374 and accounted for 15.8% of the annual national budget.

“The technical complexity of this legal instrument has allowed the public funds administered via trusts to be used in a discretionary way, with limited transparency and accountability.”

On Tuesday, the president suggested in his mañanera that the money from the dissolved trusts could be dedicated to Acapulco’s recovery. The chief justice of the Supreme Court, Norma Piña, responded quickly, accepting AMLO’s proposal, saying it “represents a real alternative that will allow us to act as a state, in defense of its population.”

Could this bring a calming of the waters?

Mario Aburto and the shadow of 1994

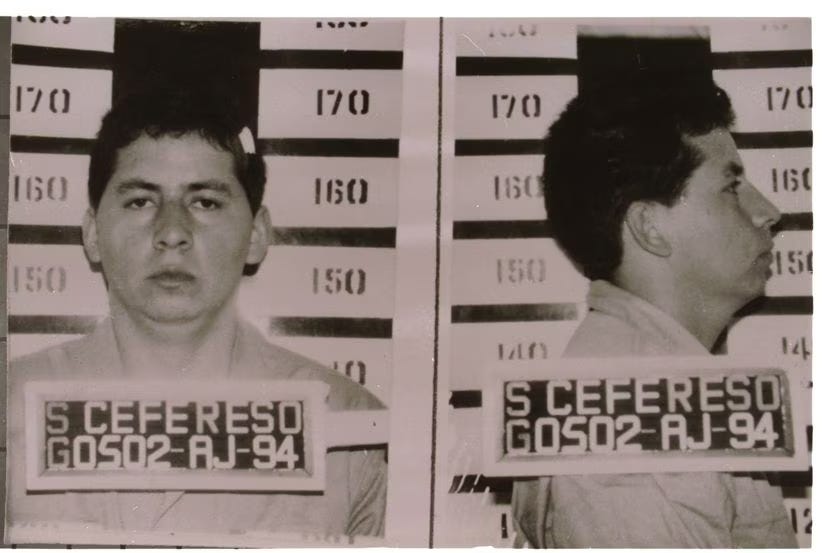

On March 23, 1994, aspiring PRI presidential candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio was shot while at a campaign rally in Tijuana. It was the first major political assassination in Mexico since President Álvaro Obregón was murdered in 1928, and it was a watershed moment in recent Mexican history.

On Oct. 6, a federal court annulled the sentence of Mario Aburto Martínez, who was convicted of murdering Colosio, and he is expected to be released before the 30-year anniversary of his arrest next March. He had been sentenced to 42 years, however, the court ruled that he should have been tried under Baja California law (where the maximum sentence would have been 30 years), not federal law. Aburto confessed to the crime at the time, and said he acted alone – which was the conclusion reached in multiple investigations – but Aburto has since recanted his confession and said it was obtained under torture.

To say most Mexicans are skeptical of the theory that Aburto (a laborer from Michoacán) acted as a “lone wolf” would be an understatement. Colosio’s campaign was at the center of a maelstrom of political forces, and he was seen as a harbinger of change within the PRI establishment. His death came a mere 17 days after a memorable speech in which he said he saw a Mexico “thirsty for justice.”

The National Human Rights Commission (CNDH), which in 2021 had requested the Colosio investigation be reopened, considers the sentence annulment a victory, “one more step towards achieving truth and justice” on what is a very long, twisted road in a confounding case.

In a 2013 book by journalist Jesús Lemus, who met Aburto in prison, he writes of the convict’s response when he asked if he murdered Colosio:

“I didn’t kill him. But when can you beat the government? If they say you did it, well, it was you and there’s no way to say otherwise.”

Is the Sinaloa Cartel done with fentanyl?

In the past few weeks, several narcomantas (narco-banners) have appeared in Sinaloa, Sonora and also in Baja California Sur that read something to the effect of “stop making and trafficking fentanyl…or else.” Signed by various allies of the Sinaloa Cartel, the banners have stirred up a lot of media interest–including in the Wall Street Journal.

In the report, the WSJ mentions not only the narcomantas, but several recent murders that appear to be tied to this shift away from fentanyl production. Insight Crime had already published a report on this back in September, following the “fast-tracked” extradition of Ovidio Guzmán to the U.S. According to their sources, the command to shut down fentanyl production and trafficking came from high up in the cartel, though they said they were not told the reason. They assumed it was related to the DEA pressure on the Mexican government and on “Los Chapitos”.

While this is plausible, I find it wanting as an argument—it’s too tidy, too…corporate. Rather than interpret these banners as the business memos of the underworld, dictating a new company-wide policy, maybe we should follow the money. After all, selling drugs on the black market is a capitalist endeavor, keenly sensitive to supply and demand:

From the WSJ report:

“Before the ban, there had been an excess production of fentanyl in Sinaloa, so the flow of the drug to the U.S. will likely continue over the short term, but the price is likely to increase, cartel members say.”

Maybe we shouldn’t count on this fentanyl ban lasting too long.