In death, as in life

The questions Isabel Miranda de Wallace leaves behind, plus the judicial election campaign comes to TikTok

Welcome to The Mexpatriate.

In today’s letter of news I cover:

Isabel Miranda de Wallace leaves a legacy of suspicion

The (very online) judicial election campaign begins

I’ve been traveling the past two weeks, but will get back to regularly scheduled programming shortly. There will be more editions landing in your inbox this week!

Isabel Miranda de Wallace leaves a legacy of suspicion

On March 8, a crime reporter named Antonio Nieto posted on his social media accounts that Isabel Miranda Torres de Wallace (age 73) had died at ABC Hospital in Mexico City following a surgery. The news spread to other media outlets, but with few details; Miranda’s social media accounts were quickly shut down.

The release of a new book titled Fabricación—not the first, and surely not the last about the infamous “Caso Wallace”—mere days after Miranda’s death raised a fresh question about this shadowy public figure.

Did the anti-kidnapping crusader fake her own death?

The public reactions to Miranda’s death demonstrated her polarizing effect on the national conversation. Former President Felipe Calderón (a staunch ally of Miranda) responded to the news with his condolences, describing her as a “tireless fighter” in a “relentless search for justice.” Rosa Icela Rodríguez, Sheinbaum’s Secretary of the Interior, sent a wreath of flowers to the funeral. But Alejandro Solalinde, a Mexican priest known for his work with migrants, described her as an “anti-woman” who represented the “rot in the judicial system.”

If you want to stay on top of the national conversation in Mexico, sign up for a paid subscription for full access.

Journalist Ricardo Raphael, who spent six years researching Miranda’s story to write Fabricación, was immediately skeptical.

He reported that some of Miranda’s family members were present at the funeral on March 9, but the casket remained closed throughout the service. On March 24, he wrote in his Milenio column that he’d had access to Miranda’s death certificate, and it indicated she died at a different hospital, located 23 kilometers away from ABC Hospital in Santa Fe.

While there is no official doubt about Miranda’s passing, the circumstances have been as opaque as many details of her life. As columnist Vanessa Romero Rocha noted: “The mere fact that her demise casts doubt is, perhaps, the most unsparing portrait of who she was.”

On July 11, 2005, Miranda reported that her 36-year-old son, businessman Hugo Alberto Wallace, had been kidnapped in Mexico City. The first arrest in what would become the nationally notorious “Caso Wallace” was made just three days later.

Though no trace was ever found of Wallace, this tangled, twisted tale of unchecked criminality and impunity grew (the case file is 130,000 pages long). It is a sprawling warren of rabbit holes.

Over the next five years, 10 people would be detained in connection to the case. Juana Hilda González, César Freyre, Jacobo Tagle, Tony Castillo and Alberto Castillo remain in prison today (all have been convicted and sentenced, except Tagle). Another suspect, Brenda Quevedo, who was held for 17 years without trial in five different prisons, was released last summer, but remains under house arrest. The suspects (or victims) were tortured on repeated occasions—some of it with Miranda as witness—to incriminate accomplices in the kidnapping and murder of Wallace.

Miranda claimed that her son had been killed and then dismembered with a chainsaw at an apartment in Colonia Extremadura Insurgentes, based on a drop of blood found in a shower. Despite the absence of a corpse, forensic analysts wrote up a “very technical” report confirming her allegations.

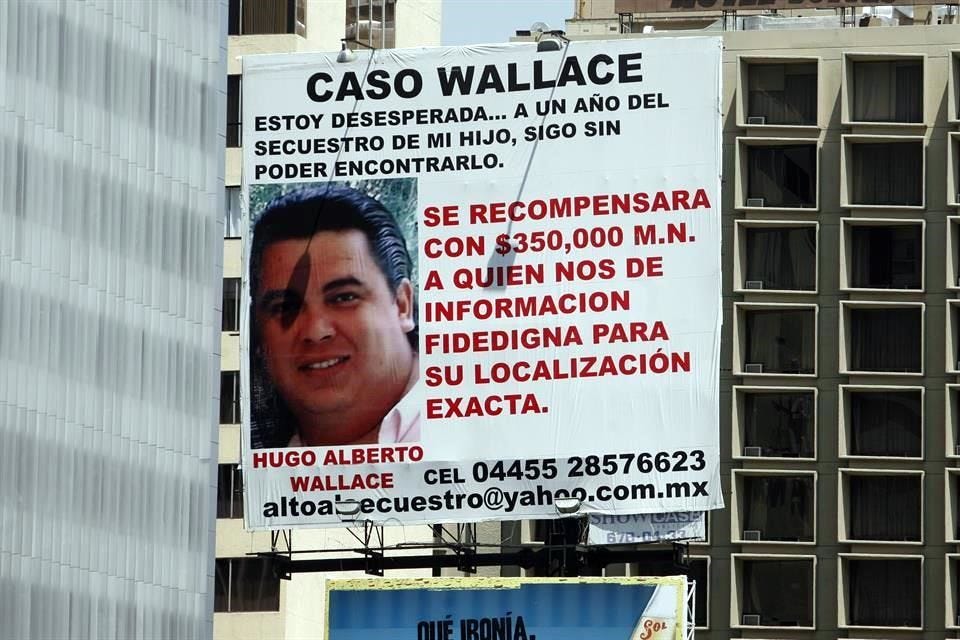

Miranda turned the hunt for her son and his alleged killers into a public spectacle, using her advertising company (Showcase). It began with massive billboards displaying Hugo’s face and the message: “I am desperate…one year after my son’s kidnapping, I still cannot find him.” Later, Miranda’s billboards turned into “Wanted” posters, with photos of alleged suspects and their names, and with an offer of reward money for anyone who turned them in.

Miranda’s spider web of influence within law enforcement, the courts and the prison system was/is extensive. She had the support not only of President Calderón (he gave her the National Human Rights Award in 2010), but also his Secretary of Public Security, Genaro García Luna (who is today serving a 38-year sentence in the U.S. for accepting cartel bribes).

Miranda ran for mayor of Mexico City as the PAN candidate in 2012 (she won 13.61% of the vote) and continued to hold sway during the administration of President Enrique Peña Nieto, using her platform to boost the government’s “historic truth” in the Ayotzinapa case.

Questioning, much less investigating, Miranda was an “extreme sport” and she was relentless in her efforts to discredit her critics and avoid scrutiny. As one example: the expert psychologist who assessed Brenda Quevedo in 2021 and verified her reports of torture in accordance with U.N. guidelines is now herself under investigation—accused by Miranda’s lawyer of falsifying her report, despite both the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) and the U.N. backing it up.

However, that drop of blood Miranda built her case on would end up revealing more about her deception than it did about a horrific crime scene. The DNA was a match with Miranda’s second husband—but he was not Hugo Wallace’s biological father. Through investigative work by Guadalupe Lizárraga, Raphael and others, the identity of Wallace’s father was discovered to be Miranda’s first husband (and cousin), Carlos León Miranda.

Another crack in the foundation of Miranda’s story is Claudia Muñoz: an ex-girlfriend of Wallace’s, and mother of his child. In 2020, she came forward to say that she had last spoken to Wallace on the phone in 2007, two years after his supposed disappearance and death. And on March 13, Muñoz was scheduled to testify legally to this claim in a Mexican consulate in Oklahoma. She told the attorneys present that she had kept quiet for years out of fear of retaliation.

As described in Raphael’s Proceso interview:

“The Isabel Miranda described in ‘Fabricación’ used an arsenal of cruel practices to further her own ends: she attended torture sessions, threatened witnesses, blackmailed judges and prosecutors, had innocent people abducted, created false documents, launched defamation campaigns and hired shady businesspeople from the security underworld.”

All of which leads to the origin question: Why did Miranda manipulate the judicial system for 20 years?

“If the death of a child can make a mother go mad, what kind of madness drives a mother to invent the death of a child?”

Raphael’s conclusion (and he is not alone) is that Wallace had links to organized crime, and owed them money. His disappearance and death may have saved his life.

Miranda developed a perverse relationship with successive governments over two decades. She gave legitimacy to hardline criminal justice policy as a crime-fighting mother in exchange for free rein to capture whoever she wished in a trap of state-sanctioned cruelty. I’m reminded of a quote attributed to one of Mexico’s madres buscadoras: “The state doesn’t look for the missing because it will find itself.”

If the law investigated Miranda or searched for the truth about Wallace, it would find itself.

Lawsuits filed by Miranda’s victims have reached the Supreme Court, but the court justices—as well as the judge in charge of four of their cases—are all up for election on June 1. If rulings are not made before then, there could be months (if not years) of further delays.

Miranda’s departure may not suffice to allow the release of her prey.

The (very online) judicial election campaign begins

“My day starts at 5:00 a.m. at the gym, because that’s when it’s quiet.”

A young man in an empty gym smiles at the camera, looking like a lifestyle influencer sharing morning routine tips. Then the video cuts to him putting on a black robe and showing viewers the courtroom where he works. This isn’t a fitness guru, but a candidate campaigning in Mexico’s unprecedented national judicial elections.

The campaigns launched on March 30 and over 4,000 candidates—operating under strict rules which ban TV and radio ads—are industriously taking to social media to get voters’ attention. In just the first week of this 60-day campaign, we’ve already been introduced to characters like “Dora La Transformadora” and “Ministro Chicharrón,” along with a bevy of young judges and magistrates who skateboard, carry Harry Potter wands and dote on their Chihuahuas. There are GRWM (Get Ready With Me) robe-donning videos, awkward Reggaetón jingles and hip hop dances—and even more awkward attempts to be serious.

And it’s not just the Gen Z attorneys exploding on TikTok—we’ve got Supreme Court Justice Lenia Batres (“Minister of the People”) lecturing on jurisprudence and reminiscing about elementary school, while her colleague Justice Loretta Ortiz Ahlf takes us shopping for gifts for her grandkids. Justice Yazmín Esquivel tells us where to get good cochinita pibil, interrupted by the taquero to make sure she gets the location right.

I can’t stop watching.

While the campaigns are generating headlines and memes, it’s dubious how effective they will be in bringing out the vote on June 1. Turnout is projected to be low (a poll published yesterday in El Financiero estimates around 20%), and those who do show up will have to navigate six ballots (which is why candidates are also uploading how-to videos and drilling their numbers and ballot colors). Without the support and structure of political parties to organize campaigns, the candidates face a steep uphill battle for votes.

I’ll be back with much more on the elections soon…

Thank you for reading and feel free to send me your suggestions, comments and questions at hola@themexpatriate.com. Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to get full access to every newsletter, and support my work.

Fascinating piece! Thanks.