La Quincena: Tuesday, Feb 21

Are we on the threshold of another Mexican "moment"?

Welcome to a Tuesday edition of The Mexpatriate.

This week, I decided to take an aerial view of the current Mexican political and economic scene, and its undisputed, loquacious prime mover: Andrés Manuel López Obrador. But rather than looking at him in his natural habitat of domestic politics, I place him in an international and historical setting.

Mexico’s true “arrival” on the global stage has been announced at several points in recent history by global observers (and former presidents). While AMLO is no darling of the international press, his country finds itself today at the intersection of geopolitical trends of economic nationalism and energy volatility that have brought renewed attention to Mexico’s economy. Has another Mexican “moment” arrived?

In today’s edition:

From the Mexican “miracle” to Mexico’s “moment”?

1994: The year Mexico survived

From the “Mexican miracle” to Mexico’s “moment”?

“Poor Mexico, so far from God, and so close to the United States.”

—Porfirio Díaz (seven times Mexico’s president, from 1876-1911)

As a charismatic political figure, Andrés Manuel López Obrador commands the national narrative; not only by telling his hero’s journey as leader of the “cuarta transformación”, but also by goading his critics to respond to a continuous stream of commentary, gaffes and medias verdades. This can obscure the fact that in some ways, his presidency has been stymied—or distracted—from its domestic ambitions by international events. A pandemic doesn’t come along every sexenio. Nor does war in Europe or seismic shifts in global supply chains.

On Feb. 3, the New York Times published an article titled “Why Chinese companies are investing billions in Mexico”, which through the story of one of China’s largest furniture manufacturers and its $300 million USD investment in a factory in Nuevo León, paints the broader picture of “nearshoring”—the biggest business buzzword in Mexico. As trade tensions have mounted between the U.S. and China, and logistics have become costlier since the pandemic-induced supply chain upsets, some businesses see Mexico as a viable option for relocating their manufacturing. The principle reason is Mexico’s proximity to and trade pact with the world’s largest market.

At the North American Leaders’ Summit (NALS) last month, a 12-person committee dedicated to growth of regional self-sufficiency was established, and shortly after, the Foreign Affairs Secretary, Marcelo Ebrard, announced intentions of North America substituting 25% of Asian imports—though he didn’t provide a timeline for this ambitious endeavor.

But do the promises of nearshoring hold up to scrutiny? Has the isolationist tabasqueño president stumbled into the oft-heralded Mexican “moment” on the world stage?

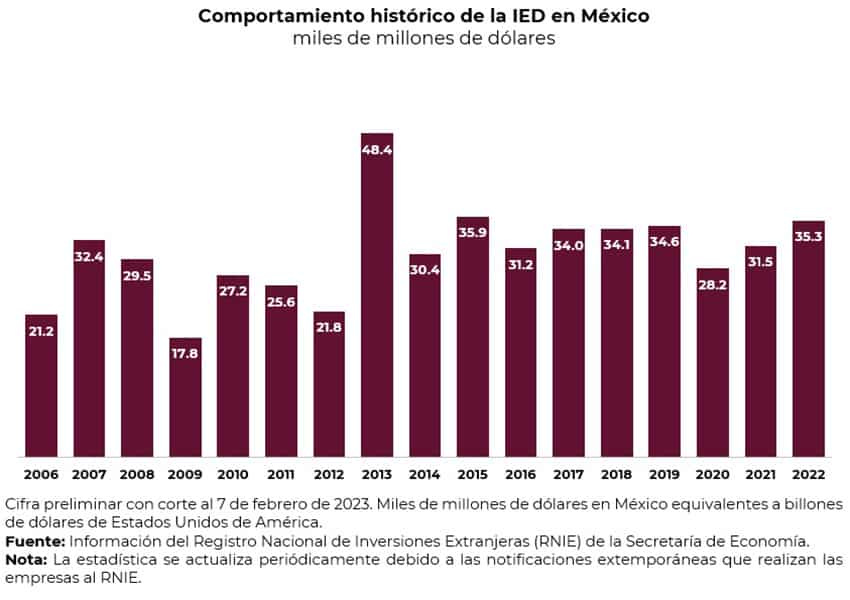

In 2022, foreign direct investment (FDI) in Mexico hit its highest point since 2015 at $35.29 billion USD according to Mexico’s Economy Department (SE), though it’s worth noting that number is still well below a peak in FDI in 2013 ($48.4 billion USD)—of this, 48% was registered as new investments in 2022, and the manufacturing sector accounted for 36% of FDI.

The U.S. continues to be the biggest investor in Mexico ($15B USD in 2022), and according to the SE, China comes in as merely the tenth biggest investor. However, economic researchers at the UNAM Center for China-Mexico Studies (Cechimex) have calculated that the amount of Chinese investment is much larger than it seems, since Chinese investors often use U.S. subsidiaries to funnel capital to Mexico. According to the academics’ estimates, the total amount of Chinese investment in Mexico since 2001 is nearly six times higher than official figures. The NY Times reported in their story that Chinese companies were responsible for 30% of investment in Nuevo León in 2021, second only to the U.S.

This all puts AMLO in an unusual position: his protectionist and nationalist impulse is encountering a favorable regional context shifting away from Asian manufacturing (coupled with Asian interest in better access to the U.S.), but his statist policies clash with private investment interests. His rhetoric and policies reveal a nostalgia for the era of the “Mexican miracle”, a period from roughly 1940-70 characterized by “import substitution” and the nationalization of industries, which did foster growth, but also saw a decline in foreign investment.

“Mexico, for example, which had practiced import substitution for decades — resulting inter alia in closed markets, slow growth, expensive and poor-quality consumer goods, and uncompetitive industrial exports — largely abandoned it in the mid-1980s,” wrote David A. Gantz, a trade and international economics professor in a brief on the NALS for the Baker Institute of Public Policy.

AMLO’s policies have also been explicitly south-facing, which he sees as a critical contrast from his predecessors. Some of this administration’s most significant infrastructure projects are based in the south, including the Tren Maya (Yucatán peninsula) and the Dos Bocas refinery (Tabasco). And yet, the flurry of nearshoring-related investment activity is almost exclusively destined for the northern manufacturing hubs: of production relocation investments in 2022 (based on data from the CBRE real estate firm), 50% was captured by the state of Nuevo León, and only one southern state (Yucatán at 8%) made the list. Just yesterday, AMLO floated the southeast as a possible destination for Tesla’s rumored manufacturing plant investment in Mexico, citing concerns about lack of water in the arid north; but the states of Nuevo León and Hidalgo have been reported as the most likely candidates.

Earlier forecasts of Mexico’s full arrival on the global economic scene were mostly focused on the country’s modernization and efforts to join the developed world. In the 1960s-70s, this meant the construction of infrastructure: public transportation (the CDMX Metro in 1969 for example), highways, universities and other public works. President Luis Echeverría (1970-76) oversaw an enviable 6% annual growth in GDP, though the country experienced an economic crisis at the end of his term leading to a peso devaluation.

All eyes turned to Mexico for the Olympics in 1968, but instead of a victorious moment, it became one of the darkest in recent history when student protesters were massacred at Tlatelolco. A shadow has fallen across each of these perceived opportunities for Mexican glory ever since: for Carlos Salinas, it would come in the shape of the Zapatistas in Chiapas, for Peña Nieto, in the atrocity at Ayotzinapa.

The presidency of Carlos Salinas de Gortari (1988-1994) marks the beginning of Mexico’s ongoing encounter with globalization. Salinas opened up Mexico to more private investment, more trade and in the opinion of AMLO and his adherents, to more exploitation—undercutting Mexican farmers and workers, threatening national sovereignty.

U.S. exports to Mexico increased by 517% from 1993 (pre-NAFTA) to now; today, 40% of Mexico’s GDP is dependent on the U.S., through exports, remittances and investment. As written in a January 1995 story in The Washington Post: “The Mexican economy, once closed, has been thrown open to the world…For many Americans, the image of the siesta-taking villager has been replaced by that of the pin-striped businessman barking orders into a cellular phone.”

While Salinas was seen abroad as the champion for Mexico as a land of opportunity, his rise to power began on shaky ground. The 1989 election showed the cracks in the PRI monolith and allowed for a democratic opposition movement to strengthen. His last year in office was a catastrophic one for the country, bookmarked by the Zapatista uprising and the peso devaluation (shortly after his successor, Ernesto Zedillo, was sworn in), with the assassination of presidential candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio in between. If you want to learn more of the backstory on 1994, read my republished overview below (published originally in 2013).

Fast forward to 2012: Mexico has now had its first “alternancia” in 70 years, with the opposition PAN (National Action Party) beating the PRI in 2000 (President Vicente Fox), and then again in 2006 (President Felipe Calderón). In economic terms, both Fox and Calderón carried on broadly with the liberalization strategy initiated under Salinas, representing the “pro-business” PAN.

And then, with the election of Enrique Peña Nieto in 2012, the PRI returned to power. But unlike the priistas of the 20th century, EPN presented himself as a reformer who would tie up the loose ends of privatization in the energy and telecommunications sectors.

In a 2012 article titled “Mexico’s Moment” in The Economist, Peña Nieto declared: “Competition in key economic sectors needs to become a reality. Therefore, establishing policies that foster competition in all sectors will be imperative.” He cited economic experts forecasting Mexico would become one of the ten largest economies in the world by 2020 (it ranks 15th today). Peña Nieto also made the cover of Time magazine in 2014 as the man “saving Mexico”, which the internet will never let him live down.

While Peña Nieto’s administration did manage to get some sweeping energy and telecommunications reform legislation through Congress, and FDI accelerated in response, one of the defining events of EPN’s sexenio was far removed from the halls of Congress and the hubs of industry: the disappearance of 43 students from the Ayotzinapa teaching college in Guerrero in September 2014. The protests that ensued engulfed the country, and laid bare the nexus of the drug trade, politics and law enforcement. Mexico’s “moment” was again muddied.

Today, the world’s geopolitical realignment has indeed reminded everyone about Mexico’s assets—mostly its relationship to the U.S.—echoing the excitement of years past. And yet, while wondering if AMLO’s policies will allow for this influx of investment to flourish, it is equally important to recall the intractable issues that lie beneath.

If we are to learn anything from recent history, it is that the underdevelopment of vast swathes of the country—profoundly lacking in access to education, healthcare, and security—cannot be wished away, whether by glossy magazine covers, or the pontifications of a leader once dubbed the “tropical Messiah”.

1994: The year Mexico survived

Originally published in May 2013

They say bad things happen in threes.

Or that's maybe what you blurt out when someone tells you about their poor friend Jerry: his wife is leaving him, her new boyfriend gave him a black eye and his goldfish just died. So you say something silly and superstitious as a sort of vicarious comfort to the unlucky victim: since you've gone through three awful things, Jerry, the Fates won't go over your quota and hit you with a fourth disaster. Unless they do—even Destiny makes miscalculations sometimes.

Exhibit A: Mexico, 1994.

This was the tough year, the one that made neighbors shake their heads and worry about the country's well-being. So, what happened in 1994? A friend of mine asked me this as we were leaving a performance of Salón Danzombie in La Fábrica Querétaro, a play that imagines a zombie apocalypse striking Mexico in that auspicious year. The playwright and director told me it was logical to pick '94 as the setting for his comedy—so much else happened, why not the arrival of the walking dead? Let's take a little tour of recent history and walk—no, run—through the year that Mexico (barely) survived.

Everyone might have been too hungover to notice, but NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) came into effect on January 1. Terrible for farmers, good for manufacturers, in a nice, sweeping generalization (who wants to fall into the quicksand of detailed economic analysis?) Also on January 1—to protest NAFTA—the EZLN (Zapatista Army of National Liberation) began an uprising in Chiapas, the first major armed civil unrest since the Cristeros War of the 1930s. Mexico had definitely woken up on the wrong side of the bed this New Year's Day.

The uprising only lasted twelve days, but it did introduce Mexico and the world to a memorable character, the mysterious masked guerrilla leader, Subcomandante Marcos.

His real name is Rafael Guillén Vicente and he is not an indigenous Maya like the rebels he led. In fact, members of his family were prominent in the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party), which he made his political nemesis. His florid, romantic and sometimes crude rhetoric has been color commentary to political games in Mexico for almost a decade. He's written manifestos and essays, as well as a detective novel and a romance that he called "pure pornography." Disdain for politicians of any stripe is one of his favorite topics; a January letter to the Peña Nieto administration referred to the president and his advisors as "Ali Baba and the 40 thieves", adding a cartoonish hand flipping them the bird.

The rebels retreated into the steamy - or should it be torrid, Subcomandante? - mountain jungles, but Mexico's poorest state would continue to fester. The country had little time to recover from the fright of upheaval; on March 23, presidential candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio was assassinated at a campaign rally in Tijuana. No prominent political figures had been murdered in Mexico since 1929 (before that, it was their expected cause of death). Police arrested Mario Aburto Martinez, who confessed and said he had acted alone. Well, we all know how convincing those words are—particularly in a place where conspiracy theories seem about as hypothetical as Newton's Laws of Gravity.

Colosio was expected to become the next president since sitting president Carlos Salinas had indicated him as successor. But competing for the national spotlight was Manuel Camacho Solis, the Foreign Secretary who was dispatched to Chiapas to broker peace negotiations with the Zapatistas. Camacho had openly discussed his aspirations to the presidency and many observers thought he was trying to win media favor and distract from Colosio's campaign. Salinas clarified that Colosio was "the candidate", in other words, to be bestowed with the presidency of Mexico. But as the campaigning continued, Colosio's speeches and interviews drifted further and further from the PRI party line; he kept talking about the "change" Mexico wanted and needed, even a "democratic transformation." He wasn't quite dismissive or damning enough when he talked about Subcomandante Marcos and his rebellion. Some think his ambiguity about the PRI's "perfect dictatorship" got him killed. Ironically, his replacement—former Colosio campaign manager Ernesto Zedillo—would be the PRI's last man in Los Pinos for twelve years.

Attempting to summarize theories about Colosio's murder is as hopeless as doing the same with all the controversy and conspiracies surrounding Kennedy's assassination. And Colosio was actually not the only newsworthy assassination in 1994. The PRI party secretary and brother-in-law of Carlos Salinas, Jose Francisco Ruiz Massieu, was killed on September 28, shot to death in Mexico City. This tangled, internecine story involves a lot of brothers: Salinas's brother, Raúl, was arrested in 1995 and convicted of masterminding the assassination, but his conviction was overturned in 2005. Ruiz Massieu's brother, Mario, was also arrested on money laundering charges and accused of obstructing the murder investigation. Mario committed suicide in 1999.

The economic situation in 1994 was fragile; the deficit was growing fast and with all the turmoil, foreign investment kept a safe distance. In December, the strain on the country's finances became acute: the peso crashed, losing one-third of its value and delivering a huge blow to the country's nascent middle class. According to a Stanford University report: "Following the forced devaluation of the peso on December 20, 1994, Mexico faced its worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. Real GNP per capita fell 9.2 percent in 1995 and mean manufacturing wages fell by 21 percent over the 1994-96 period." Mexico would end up receiving around $50 billion USD in loans from the US, the IMF, the Bank for International Settlements and the Bank of Canada.

Mexico also suffered a sports trauma in 1994: their national soccer team was eliminated from the World Cup after losing to Bulgaria. And then there was the horrible drought in Chihuahua, Hurricane Rosa on the Pacific coast. Not to mention, the most rumbling and spewing from Popocatépetl that had been recorded since the Spanish conquest. 50,000 people were evacuated from the foot of the volcano as it rained apocalyptic ash on the metropolis.

Oh, and zombies began prowling the streets and feeding on the living. Kind of fits right in, doesn't it?

Note: I recommend the 2019 Netflix documentary series 1994 for a worthwhile overview of this tumultuous period.

Before you go, I’d like to extend my gratitude and a welcome to new subscribers to The Mexpatriate.

I would love to hear more from you in the comments—please share your feedback and suggestions for topics to cover. You can also email me at hola@themexpatriate.com.