La Semana: July 23, 2023

I'm not campaigning...you're campaigning

Welcome to a Sunday round-up edition of The Mexpatriate.

I’ve been off for a few weeks in which the headlines were dominated by the rise of opposition candidate Xóchitl Gálvez, the murder of Michoacán auto defensas (self-defense) leader Hipólito Mora, a car bombing in Celaya, an IED explosion in Jalisco, a Pemex offshore platform accident in the Gulf of Mexico…

And this week started with a real-life survival story when Mexican fishermen rescued an Australian sailor and his dog after three months at sea, and ended in nuclear pink fantasy land with the summer’s movie marketing juggernaut: “Barbenheimer”, the “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer” double feature.

Grab a plate of pink tacos, and get caught up on the events of the last few semanas.

Mum’s the word, Mr. President

One of the notable features of Mexican electoral politics is the restrictions surrounding the length of campaigns, which some analysts have described as a hopeless endeavor to keep politicians from…well, doing politics.

From a U.S. perspective, where marathon multiyear campaigns are the norm, it seems like putting limits on their duration is a good idea. In fact, the U.S. is an outlier among global democracies in this regard.

But, laws don’t always shape policy the way you’d expect—instead of promoting more circumspect campaigns, Mexico’s regulation seems to have catalyzed creative loopholing. Hence, the semantic contortions of the Morena party referring to the selection of the “defender of the fourth transformation”, rather than “candidate” in their internal process launched last month.

And this week, President López Obrador took this electoral cheekiness further. On July 13 he was ordered by the National Electoral Institute (INE) to stop discussing the 2024 elections after PAN senator (and presidential hopeful) Xóchitl Gálvez filed a complaint about his derogatory comments in the daily press conferences. In response, AMLO created a new segment called “It’s not me saying it”, in which he uses quotes from others to get his message across.

The National Electoral Institute (INE) has established that the pre-campaign period for the 2024 elections will begin in September, which is when both the Morena party and the opposition “Frente Amplio” coalition will announce their chosen leaders. As both sides are being scrutinized for “anticipated campaign acts”, the national electoral tribunal ruled last week that while the parties’ pre-pre-campaign activities will not be suspended, the INE has five days to come up with guidelines to regulate them. Genie, get back in your bottle, and unring those bells!

Xóchitl Gálvez: the anti-AMLO AMLO?

The PAN-PRI-PRD opposition “Va por México” coalition launched its candidate selection process on June 26, with plans to announce the selection on Sept. 3 (three days before Morena’s announcement). The coalition has re-branded as the “Frente Amplio por México” (broad front) and it did indeed start out quite broad, with 33 hopefuls. As of today, that number has been whittled down to 12, with three who are widely considered real possibilities: Santiago Creel, Enrique de la Madrid and Xóchitl Gálvez.

The latter has wrested the media spotlight away from the Morena “corcholatas” and from her fellow opposition aspirants by an active social media presence and a flurry of coverage in outlets nationally and internationally—The Guardian and the Associated Press both ran profiles of her this week. Gálvez has also joked that AMLO is her campaign manager: the president has been vociferous in his criticisms, and insists that the opposition has already anointed Gálvez to run in 2024.

There is a lot to explore here, from Gálvez herself to the online fandom she’s inspired, but the biggest takeaway for now is that she has sparked something in Mexico’s “seemingly soulless” opposition (as described in The Guardian). She is a candidate who ticks off some politically advantageous boxes in a battle with Morena: a woman of indigenous heritage born not to privilege, but to poverty. As highlighted in the AP story’s headline, she sold tamales and gelatinas with her mother, and in her own telling, this fostered her entrepreneurial spirit. She went on to study computer engineering and founded her own business. Her political resumé is thin: she was the head of the indigenous affairs department under President Vicente Fox and mayor of the Miguel Hidalgo borough of Mexico City (home to high-income neighborhoods like Polanco and Lomas de Chapultepec). She ran for governor of Hidalgo in 2010 (and lost), and became a PAN senator for Mexico City in 2018.

Her story is an appealing one, particularly for voters disillusioned by López Obrador, but turned off by the prospect of a more conventional PAN or PRI candidate. While her political experience is limited (and she has unclear ideological affiliations), she seems to possess sharp political instincts and a style not unlike the the president’s: folksy, approachable and unscripted. In order to advance in the “Frente Amplio” candidate selection process, Gálvez has to obtain 150,000 signatures of support. She claimed last week that she will surpass this number, and has relied solely on self-funded promotion via social media. A Twitter account called “Xochilov_rs” has used AI to create videos of a Gálvez bot, accompanied by sweeping music and imagery, that have gone viral.

According to a July 18 poll in El Financiero, Gálvez is the most popular of the opposition candidates, six points ahead of the second-most popular, veteran PAN politician Santiago Creel. However, “wars aren’t won in the air, they are won with infantry on the ground,” as described by political analyst Sabino Bastidas, and it is very early to predict whether Gálvez—under the wing of the tainted PAN and PRI brands—could mobilize across a country dominated by Morena.

Mandatory pre-trial detention eliminated in 18 states

This is one of those news stories that seems to be flying below the radar, but could signal a landmark shift in Mexico’s rule of law.

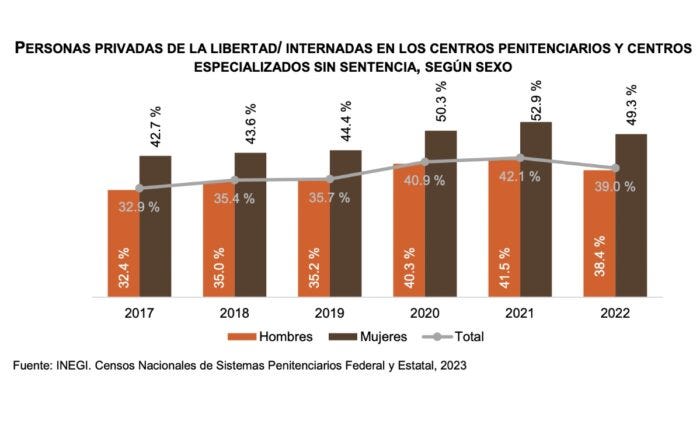

In 2019, the number of crimes that merited mandatory pre-trial detention (prisión preventiva oficiosa) was expanded to twenty. If a citizen was accused of one of these offenses and arrested, he or she would automatically go to prison pending trial. According to data from 2022, 39% of Mexico’s prison population has never been sentenced (down slightly from 42.1% in 2021). In other words, they are presumed guilty.

A regional court has ruled to eliminate mandatory pre-trial detention in 18 states: Mexico City, México state, Nuevo León, Sonora, Coahuila, San Luis Potosí, Sinaloa, Baja California, Guanajuato, Chihuahua, Tamaulipas, Querétaro, Zacatecas, Nayarit, Durango, Baja California Sur, Tlaxcala and Aguascalientes. Twice this year, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights had ordered the Mexican government to eliminate the practice in order to comply with the American Convention on Human Rights, and Amnesty International has praised this ruling against a legal tool that is “contrary to human rights.”

Is Mexico experiencing “narco-terrorism”?

The national conversation about violence is a weary one.

President López Obrador acknowledged last week that his term will end as the most violent on record, though he emphasized that this is what his government inherited, a “narco-state” and over a decade of escalating violence. His government has also been keen to point to a plateau in national homicide numbers, even declines in some parts of the country. But the statistics feel hollow when confronted with the shocking episodes in the past month that have led some to speculate about the emergence of “narco-terrorism.”

First, there was the murder of 67 year-old Hipólito Mora and three bodyguards on June 30, in the Michoacán town where he founded the first autodefensas a decade ago. Mora’s armored vehicle was shot with thousands of high caliber bullets, and set on fire. Mora was a lime farmer who took up arms against the Knights Templar cartel in 2013 and began the state’s vigilante movement to protect communities from extortion and violence. He had stated in recent years that the security situation was “worse than ever”.

Then came the kidnapping of 16 public security employees in Ocozocoautla, Chiapas by a group that claimed the authorities were colluding with another criminal group responsible for kidnapping a young woman from the area. The officials were freed, unharmed, after the mobilization of 1,000 law enforcement agents to the area, leaving more questions than answers.

On June 29, a car bomb in Celaya injured 10 National Guard members in what appeared to be a trap: they were called to investigate an abandoned vehicle on the road between Celaya and Salvatierra.

And in Tlajomulco, Jalisco, an improvised bomb attack killed 6 people and injured 14 on July 11. Again, it appeared to be a trap set for law enforcement, who said they received an anonymous tip about a hidden grave site. Seven IEDs exploded on the road to the site.

In the face of these (and other) recent incidents, some commentators brought the word “terrorism” into the conversation. In fact, the governor of Jalisco, Enrique Alfaro, described the IED attack as an “act of terror”. However, terrorism is not about the means of violence, but the ends. While violence is increasingly common in Mexican politics (in 2021, 90 politicians or candidates were murdered nationwide), this doesn’t mean it’s political violence, rooted in ideology. These attacks on law enforcement (and collateral bystanders) do not seem coordinated, but rather localized messages of intimidation. They are also bold exhibitions of impunity. Analyst Viridiana Ríos says these incidents show “there is a lack of information, intelligence, preventive action…we have law enforcement that has been overtaken, and they leave us wondering ‘what is their strategy?’ It’s not clear what they are doing…to enforce the law.”

Thank you for reading, and as always, send me your feedback by commenting below or sending an email to hola@themexpatriate.com.

Great read, and I loved the title!!

I’m going to be thinking about the meaning of war vs. terrorism vs. good old-fashioned violence today...