La Semana: Monday, June 6

The week in indigenous rights and freedom of expression

Welcome to the Monday edition of The Mexpatriate. In today’s newsletter:

One state, many nations: indigenous rights in Mexico

Reflections on freedom of expression

Please send me your comments, feedback and questions, and feel free to forward this to anyone who may be interested. You will find all sources linked to directly in the body of the text.

**Elections were held in 6 Mexican states yesterday**

It appears that MORENA was victor in 4 of the 6 contests (Oaxaca, Quintana Roo, Tamaulipas, Hidalgo), while the PAN-PRI-PRD coalition won Aguascalientes and Durango. The results will be key for understanding the political map as we approach the presidential election in 2024. If you’re curious to learn more, check out my field guide to the elections from the May 30 edition.

One state, many nations: indigenous rights in Mexico

“When a language dies, so much more than words are lost. Language is the dwelling place of ideas that do not exist anywhere else.”

Robin Wall Kimmerer

“We will continue our fight until our lands are restored. We can claim victory the moment that they have given back the last hectare, the last centimeter of land to our community.” After a 32-day journey on foot from the north of Jalisco to the doors of the Palacio Nacional in Mexico City, 200 members of the Wixárika people, the “Caravan for Wixárika Dignity and Conscience”, finally achieved their goal: a meeting with the president himself. On May 30, three days after their arrival in the city where they set up camp outside the seat of government, President López Obrador held a meeting with five spokespeople and signed an agreement to intervene in their land dispute.

The wixaritari (also known as huichol) live in parts of what is now Jalisco, Durango, Nayarit and Zacatecas and also further north, in the southwestern United States. According to 2010 census data, there are 59,820 wixaritari in Mexico, making up a portion of the estimated 15.1% of the total indigenous population of the country, which comprises 68 distinct groups and languages. Known for their intricate, vividly colorful art and for sacred rituals surrounding the use of peyote, the Wixárika have broader cultural recognition than most of the indigenous nations who have lived here for thousands of years. Since 2007 the communities of Tuxpan and San Sebastián Teponahuaxtlán have been in a legal battle with cattle ranchers from Nayarit who moved onto their lands, where the Wixárika live as subsistence farmers and artisans. “They have defended their rights in civil and agrarian court cases that have lasted for decades; they have protested; they have marched to Guadalajara; and they have publicly denounced the trespassing; agrarian courts have ruled in their favor. There is just one thing missing: that the Mexican state enforce justice.” In 2017, AMLO visited the community and promised to uphold the legal resolution to restore the lands, but according to the comuneros, nothing has happened since he became president.

“This government is very nationalistic and loves to identify with indigenous peoples,” says Mixe linguist Yásnaya Elena Gil. “The president has demanded that the Spanish government issue an apology—on behalf of the indigenous people—but in doing so, he completely usurps our voice.” AMLO’s visit to the Wixárika community the year before he was elected was a part of this political strategy, a show of solidarity with the many nations within the Mexican state. But when it comes to policy, the rigid reality of nationalism—the promotion of the “mestizaje” and modern Mexico—clashes with the fluid plurality of ethnic and linguistic diversity on the ground. The tension between the impulse to preserve and celebrate multicultural traditions as curiosities or artifacts versus the desire of the peoples themselves for self-determination, can be witnessed all over the world. The creation of nation-states in the 19th and 20th centuries laid the foundation for the modern age and even today, states recoil from the movement towards autonomy of minority ethnicities or regions.

According to UNESCO, there are more than 7,000 languages spoken worldwide and 6,700 are classified as “indigenous languages”, in other words, they are native to a particular region. Forty percent of these languages are endangered. In a decision that has been criticized by advocates for indigenous languages in Mexico, the federal government has been considering—in the name of austerity—the absorption of the National Institute of Indigenous Languages (INALI) into another agency, the National Institute of Indigenous Peoples (INPI).

“The indigenous communities insist that the INALI should remain as an agency devoted specifically to the development of these languages, in all areas, from research to public policy and the training of linguists, interpreters and translators,” explains Zapoteca activist and poet Irma Pineda. In 2003, the General Law of Linguistic Rights for Indigenous Peoples established that these languages have “the same validity [as Spanish] in the territory, location and context where they are spoken” and also for “any issue or procedure of a public nature”. In 2008, the agency published a National Catalogue of Indigenous Languages (CNLI) after extensive research and data collection. Some of the languages in question had only a few dozen speakers left.

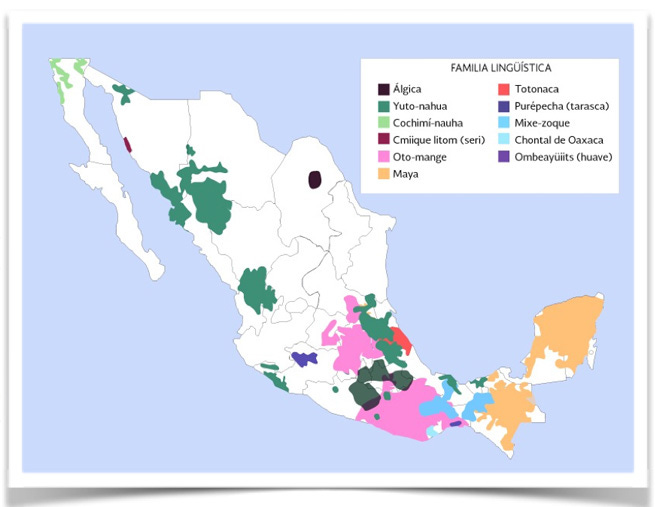

The CNLI established that Mexico is home to eleven distinct language families, divided into 68 “linguistic groups” and 364 “variants”. Nahuatl is the most widely spoken of these, followed by Maya, and the distribution of indigenous language speakers is concentrated in certain regions. For example, in Guanajuato only 0.2% of the population age 3 or older speaks an indigenous language while in Oaxaca, that figure is 31.2%.

“It has taken many years, and cost much blood and suffering in an as yet unresolved struggle, for the countries of Mesoamerica, notably Mexico, to recognize their multicultural and plurilinguistic identity,” writes renowned scholar and linguist Miguel León-Portilla in the anthology “In the Language of Kings.” “Global cultural trends induced by hegemonic powers—nation-states and transnational corporations—tend to homogenize worldviews, beliefs and moral values…Then and now, literary output has played and continues to play a crucial role.”

Speaking across centuries, the ancient poems, songs and histories told in Nahuatl, Otomí, Mixtec, Maya, Zapotec, Mazatec and many other tongues can still reach us, even as their descendants dwindle.

Though it be Jade

(Songs of Nezahualcoyotl, 15th century CE)

I, Nezahualcoyotl, ask this:

do we truly live on earth?

Not forever here,

only a little while.

Even jade breaks,

golden things fall apart,

precious feathers fade;

not forever on earth,

only a moment here.

Reflections on freedom of expression

“If there was a rule of law in this country, then journalists would not need protection.”

If anyone embodies the resilience of free speech in the face of intimidation, it is Adela Navarro Bello, general director of Semanario Zeta, the Tijuana newspaper that has unflinchingly covered drug trafficking and government corruption since 1980. *Pop culture note: Navarro is the inspiration for the young journalist Andrea in the third season of Netflix’s “Narcos México”.* In an interview with Letras Libres, Navarro reviews the history of the newspaper, which is a microcosm of the story of threats to Mexican journalism in the last 50 years.

“Blancornelas [founder of Semanario Zeta] decided to create a newspaper that would be produced in Tijuana but printed in El Cajón, California, a city 40 minutes from the border. In this way, Blancornelas did not depend in any way on the Mexican government, which controlled the paper.” When she says “the paper”, she is referring literally to the paper that all periodicals were printed on and which was how the government indirectly censored freedom of speech. According to some analysts, the increase in violence committed against journalists from 1980 on can be traced to the shift away from government censorship, which emboldened reporters to begin exposing crime and corruption and quickly to start losing their lives, instead of their access to paper and ink.

Tomorrow, June 7, is “Día de la Libertad de Expresión” in México and it is a moment to reflect on how this right is under threat. There are the most glaring obvious ways, the self-censorship caused by violence and intimidation, or outright government censorship. But there is of course more subtle erosion at work. Corporate censorship is one of the most challenging issues of our time as social media platforms not only consume our attention, but also engage in a widening scope of content moderation using algorithms that can influence which voices are heard and which are suppressed.

There is also the force of cultural hegemony, an inevitable consequence of globalization that continues to erase plurality, sometimes in surprising ways. While we on the one hand uphold the ideal of cultural diversity as a universal good, we may be blind to how the homogenizing forces of the “age of information” paradoxically eliminate it. I recently read a thought-provoking essay about the disappearance of vendors’ iconic hand-painted signs in the Cuauhtémoc district of Mexico City: the government has been replacing them with sterile signage displaying the administration’s logo and the slogan “This is your home.” When an outcry ensued, the mayor of the district, Sandra Cuevas, defended the decision as part of an effort to bring “order and discpline” and “create a better urban image.”

Does the sanitization of “arte callejero” rise to the level of a threat against freedom of expression? In the context of the violence perpetrated against journalists in this country, perhaps it seems a frivolous question. But considering the multiplicity of forms of expression and ways they can be undermined may help us to stay vigilant, to protect the right to dissent and the pursuit of truth.