¡Buenas tardes!

Welcome to this week’s edition (one day late!) of The Mexpatriate. In today’s newsletter:

Anti-inflationary rhetoric from AMLO

Disappearances in Mexico: Part I

La Semana will return to its normal schedule this Sunday, May 15.

Please send me your comments, feedback and questions, and feel free to forward this to anyone who may be interested. You can always find all sources (with links) at the bottom of the email.

Anti-inflationary rhetoric from AMLO

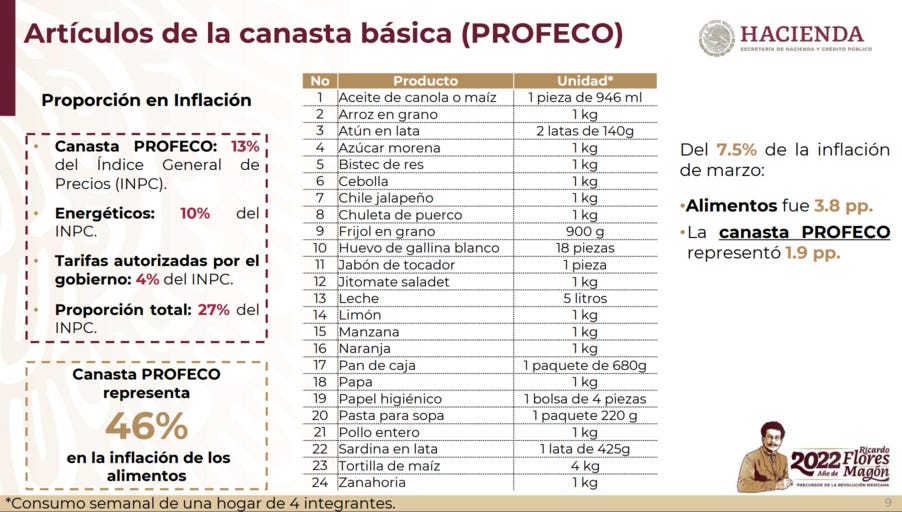

President López Obrador does not usually take time to give accolades to big business in his mañaneras, but on May 4 he expressed his gratitude to giants of the private sector—Bimbo, Wal-Mart, Chedraui and others—for working with his government on an anti-inflation plan in which they will “voluntarily participate in stabilizing the price of 24 staple products” for six months. The president emphasized this does not mean controlling prices by decree, but rather an “alliance” with businesses to address their escalation.

Inflation in Mexico reached 7.74% in April, the highest rate in 21 years. One kilo of tortillas costs up to 17% more than it did one year ago. “It is very complicated for any government to reduce inflation; we are living through global inflation and in this context, it is difficult to take isolated action,” noted Carlos Serrano, chief economist at BBVA bank in an interview. “The effects [of this plan ] will be marginal…The BBVA forecast inflation rates for this year will not change.”

The “canasta básica” (basket of staples) is mostly made up of food items such as beans, corn, milk, bread, onions, tomatoes, etc but also includes soap and toilet paper. Carlos Slim has also agreed to maintain current prices of Telmex and Telcel internet and phone services.

Analysts point out that the “Anti-Inflation and High Prices Package” (PACIC) includes measures that were already in place, such as the elimination of the IEPS tax on gasoline, natural gas and electricity and AMLO’s agricultural programs, though the plan mentions distributing more fertilizer in efforts to stimulate production of staple crops such as corn, beans and rice. The proposal also includes “fortifying roadway security” and “reducing costs and time in customs”, which would seem to be standard government responsibilities rather than innovative strategies to combat inflation.

There are a few surprises in the initiative, such as the elimination of import tariffs on a number of the 24 staple goods, some of which are heavily protected by duties of up to 75%. It is unclear how the fallout will be addressed for Mexican producers who will now be competing with imported goods. “The announced import tariff reduction will last for six months…What happens at the end of this period? Will the previous tariffs come back into effect? Will there be a gradual plan to reduce tariffs? Will producers be compensated for their losses? We do not know any of this yet,” writes economist Valeria Moy in El País México.

The PACIC does not mention small and medium-sized businesses in the fight against inflation and as pointed out by Jesús Carrillo of IMCO (Mexican Institute on Competitiveness), “large businesses have bigger margins.” Wal-Mart can make up for profits lost to lower prices on certain items by raising others, but it is harder for the tiendita down the street to make similar adjustments.

López Obrador said he had asked Banxico (Mexico’s central bank) to not raise interest rates more, but they are expected to next week, as many other central banks around the world do the same in an effort to tamp down inflation.

Disappearances in Mexico: Part I

On one side, there are only names: and on the other, nameless bodies. Two parallel columns of statistics—99,787 missing and 52,000 unidentified dead—that reveal the abysmal negligence of the Mexican state.

“Between 2006 and 2021, there is an exponential growth of disappearances in the country, an increase of 98%. This shows the close relation between the beginning of the ‘guerra contra el narcotráfico’ begun in Felipe Calderón’s term (2006-12) and he increased disappearances.” Forensic experts have concluded that it would take 120 years for the remains of victims to be identified under current conditions, which is referred to as a “forensic crisis” in the United Nations Committee on Enforced Disappearances (CED) report on Mexico, published April 12.

“In Mexico there is one actor that does not want to find the disappeared, dead or alive: the system. A system that has no strict standards, no clear protocols, no budget, no staff and no sensitivity,” says journalist Sandra Romandía, who reports the story of one family’s tortured experience after their adult son was kidnapped. They were contacted for ransom, which they paid. Then…silence. For months, there was no word from their son or the kidnappers until they were told that their son’s body might be in a morgue in another state. They gave DNA to the attorney general’s office in their state and tried to follow the official bureaucratic maze to find out the truth. “After spending hours traveling through the country with the knowledge that their hope of waiting to hear from Luis would probably end, the prosecutor’s office said no, there was no body there that matched their information and they should go home. Just like that, as if it was some laundry they had come to pick up and it wasn’t ready.”

They persisted, and eventually were told that yes, there was indeed a corpse that could be Luis, which the DNA results later confirmed.

This is one of thousands of stories behind the statistics. “How can we discuss the disappearances without it becoming just lists of numbers and despair?” asks the host of the podcast “Semanario Gatopardo”, Fernanda Caso, in an episode about female disappearances. These account for approximately 25% of the missing in Mexico.

I too have struggled to find a way in: how to write about a topic so easily sensationalized by the media and so readily dismissed by those in power, or those who feel numbed by the abject litany of loss, myself included.

One of the U.N. report’s many recommendations—ranging from coherent national protocols for law enforcement handling a missing person report to better inter-agency communication—concerns raising awareness and empathy. “There should be a broad national public awareness campaign that reaches all sectors of the population…to combat the stigma faced every day by the victims.”

To me, this means: don’t look away. Don’t “other” the men, women, children who have vanished. See them. Stand witness.

I will divide this into a two-part series: this first part provides an overview of the disappearances and the societal response. The second part will dive into the backlog of unidentified victims, the state of forensic investigation and recent efforts to centralize DNA information in Mexico.

The U.N. Committee on Enforced Disappearances (CED) made their official visit in November 2021. They had first requested the visit back in 2013, but were not granted permission until August 2021. This reluctance on the part of the Mexican state stems from an implied responsibility for human rights violations, since an “enforced disappearance” occurs when “persons are arrested, detained or abducted against their will or otherwise deprived of their liberty by officials of different branches or levels of Government, or by organized groups or private individuals acting on behalf of, or with the support, direct or indirect, consent or acquiescence of the Government, followed by a refusal to disclose the fate or whereabouts of the persons concerned or a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of their liberty, which places such persons outside the protection of the law.”

Mexico signed and ratified the International Convention for the Protection of all Persons from Enforced Disappearance governed by the CED in 2007.

While acknowledging the cooperation and “empathy” shown by some members of law enforcement and government in Mexico, the conclusions of the CED report are damning.

“The Committee expresses profound concern for the overall problem of disappearances all over the country, in which there is nearly absolute impunity and re-victimization…the disappearance of people in Mexico is everyone’s problem: one for both this society and all humanity.”

While the López Obrador administration was the first to allow access to the CED, the president’s response to their report was indignant: “If we act within the law, with humanity, if we do not tolerate corruption or impunity, what can they [CED] do? Nothing. Fabricate, that is all.”

On May 8, a group of families of the disappeared created an “anti-monument” on the site of the Glorieta de La Palma in Mexico City, placing photos and posters with messages to their missing loved ones. The iconic 100 year-old palm tree that once stood sentinel at this glorieta had been removed the week before, victim of a fungus which is killing many palms in the city. Today the site was once again empty: the materials left by the families had been removed by the city. “Their faces are a memorial which you want to make disappear again,” was the accusation made against mayor Claudia Sheinbaum by Our United Force for the Disappeared in Mexico (FUNDEM).

On May 5, family members of two gas deliverymen who disappeared near Toluca last April blocked part of the Mexico-Toluca highway, demanding answers from the state attorney general. “One year later, there has been no progress in the investigation,” they claim.

According to the U.N. report, between 2% and 6% of all cases of missing persons in Mexico have been processed through the judicial system, and only 36 sentences have been issued nationally. The lack of investigative resources and willpower is staggering, but also not surprising considering that law enforcement agencies are understaffed with underpaid employees who are often forced to pay out of pocket for expenses related to investigative work, and in offices that do not even have enough desks for the staff.

There is also a severe lack of cross-communication amongst law enforcement, military, immigration control and other agencies leading to families reporting a person missing who was detained by authorities, but no one knows where he or she is being held. The report recommends more use of the “amparo buscador”, a form of injunction that allows one government body to order another one to share information and to present or transfer a person who is in custody.

Cuartos Vacíos (Empty Rooms) is one example of how a society responds when it finds itself carrying the burden of criminal investigations. Created by the Mexican Association of Kidnapped and Missing Children (AMNRDAC) in conjunction with a publicity agency, the campaign broadcasts information about missing young women by listing their empty bedrooms “for rent” on real estate rental platforms, as well as social media. Donors contribute to the cause of the families by “paying rent”.

The mother of Karla Adriana Bolaños (16), who had been missing for over a year, expressed her gratitude for Cuartos Vacíos: “I am overjoyed to have found my daughter. We were invited to be a part of the initiative, where they spread the word about Karla, posted her photo, and we also received financial support. People have been so kind and wanted to help.” As the investigation is ongoing, Karla’s family has not released further details about the case.

There are three other “empty bedrooms” listed so far, but they have plans to expand. “In Mexico, thousands of women disappear, year after year, and their families have to live with not only the pain, but with the economic burden of spreading the word and searching for the victim. Our goal is to generate donations and awareness.”

In the words of policy analyst and writer Edna Jaime, director of the think tank México Evalúa:

“The CED report brought this issue of disappearances into the public eye for a few days. And we Mexicans turned to look at the problem. What is important is to not let it fade. What I propose is simple: we must follow up on these statistics regularly, so that we do not forget and we do not let the authorities forget how many empty chairs there are at family tables all over the country.”

Sources

1.

Plan del gobierno contra la inflación (Animal Político)

“Plan Anti-inflación” (Peras y Manzanas podcast)

Producción de granos, suspender aranceles, y más seguridad en carrerteras, el plan de AMLO para frenar la inflación (Animal Político)

Mexico to boost output of staple foods in plan to curb inflation (Reuters)

2.

Informe de la ONU sobre personas desaparecidas (Centro Prodh)

La persona que no quiere que se encuentre a quienes desaparecieron (Opinón 51)

Semanario Gatopardo: Las deficiencias en las búsquedas de las mujeres

Colectivos colocan anti-monumento en Glorieta de la Palma (Animal Político)

Con iniciativa “Cuartos Vacíos” hallan con vida a Karla (Animal Político)

Familias de desaparecidos bloquean la carretera México-Toluca (Animal Político)

Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances Fact Sheet No. 6 (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights)

Una silla vacía (Opinón 51)