La Semana: Sunday, Feb 27

The week in avocado exports and a look back at perils faced by Mexican journalists

¡Buenos días!

Welcome to the Sunday edition of The Mexpatriate.

In today’s newsletter, I cover just one current topic for the week and am re-publishing a piece I wrote in 2013 about the dangers faced by Mexican journalists, which is sadly as relevant today as it was nine years ago.

“La Semana Negra” exposes the dark side of avocado production

Journalists: Witnesses and Victims (from the 2013 archive)

Please send me your comments, feedback and questions, and feel free to forward this to anyone who may be interested. You can always find all sources (with links) at the bottom of the email.

“La Semana Negra” exposes the dark side of avocado production

On a family trip to Michoacán in 2019, I remember asking a waiter for guacamole at a restaurant near the bustling, charming town square of Santa Clara del Cobre. He replied with regret: “sorry we don’t have it, no aguacates.” I was taken aback: here, surrounded by thousands of hectares planted with “green gold”, no guacamole? The waiter explained that scarcity (more than half of the crop is exported) and rising prices had made it untenable for locals. How had the fruit become unattainable in its land of origin?

“The empire of avocados is little brother to the empire of heroin,” noted journalist Heriberto Paredes.

When the U.S. announced it was suspending all avocado imports from Mexico on Feb. 11, the buzz was audible on both sides of the border. In Uruapan, Michoacán, a USDA inspector had received death threats by phone after apparently denying the export permit for a shipment of avocados. “Ordering a drastic, sweeping and immediate measure was the best way to send a message that no matter who was behind the threat, heading in that direction would be costly,” noted an article in El Financiero regarding the U.S. import ban.

Avocados rank as Mexico’s third largest export product (in 2017 their value surpassed petroleum net exports) and Mexican avocados dominate the U.S. market: 76% of imported avocados come from Mexico, and the state of Michoacán is the only one certified to USDA standards. According to the Consultant Group on Agricultural Markets (GCMA), the avocado business provides an estimated 300,000 direct and indirect jobs in Mexico and generated $2.8 billion USD in revenue in 2021. The emergence of any commodity on this scale creates a shadow opportunity, and for the last decade, organized crime has become deeply enmeshed in the cultivation, harvest, packaging and distribution of avocados in Michoacán. Some citizens have formed militias to protect their avocado farms in the face of extorsion and violence. “The empire of avocados is little brother to the empire of heroin,” noted journalist Heriberto Paredes.

Imports were allowed to resume on Feb. 18 after Mexican officials presented an “emergency” plan to their U.S. counterparts that will include the creation of an intelligence unit in the primary avocado-producing municipalities in Michoacán, as well as “additional measures” to guarantee the safety of U.S. inspectors. During “la semana negra”, producers estimated losses of $50 million USD. President López Obrador speculated on ulterior motives behind the suspension in his Feb. 14 morning press conference: “In all of this there are a lot of economic and political interests, there is competition…there are other countries interested in selling avocados.”

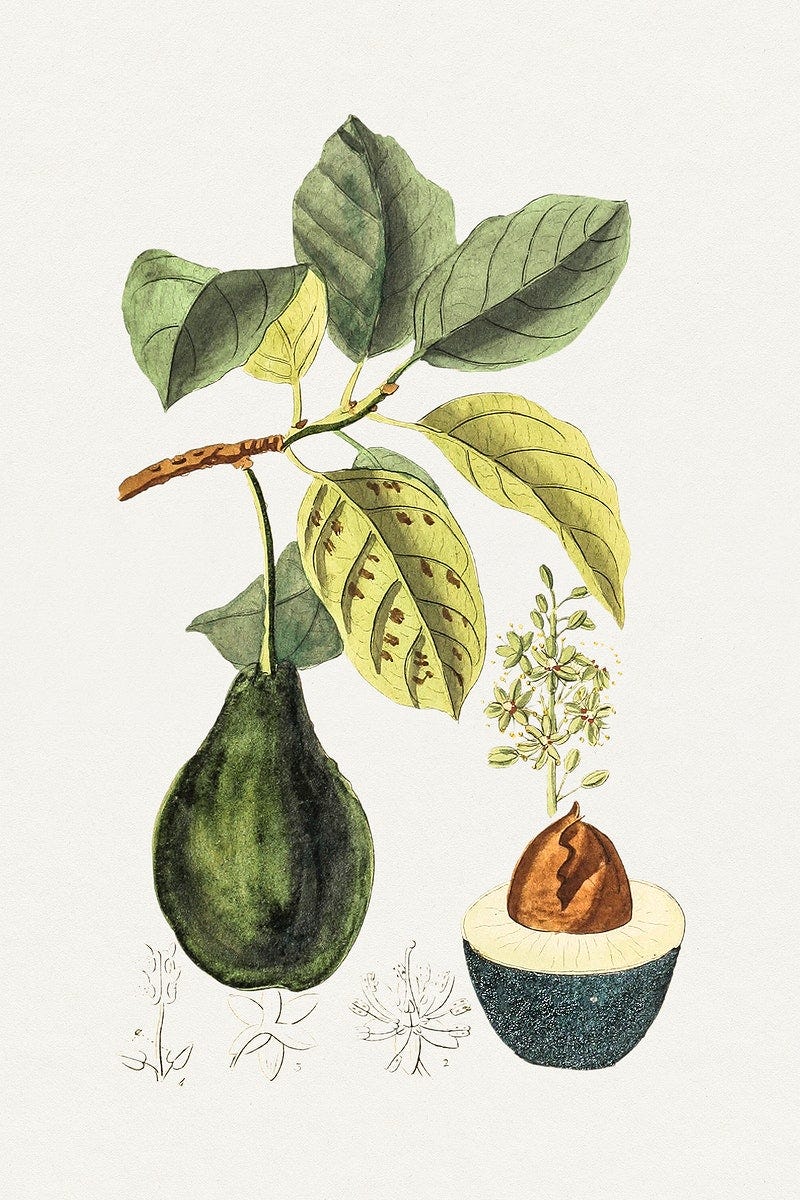

Ahuacatl is the Nahuatl name for the fruits of the persea americana tree and is often translated to mean “testicle.” There appears to be some debate among linguists on the accuracy of this: I read one conjecture that the male body part was named for the fruit, not the other way around. The avocado fruit, technically a large berry, appears to some biologists to have evolved with mega-fauna, herbivores large enough to have consumed the entire fruit and excreted the single large seed. While the avocados lost the mammoths and giant ground sloths to extinction, their evolution took an interesting turn when discovered by millennials: in the U.S. alone, per capita annual consumption grew from 2 pounds to 9 pounds between 2001 and 2020. What’s not to love? Loaded with monounsaturated fats, vitamin E and fiber, versatile in the kitchen—avocado mousse anyone?—and simply delicious. They sell themselves…though they also have a massive PR team that has pushed guacamole as the essential appetizer at every Superbowl party and as the best topping for every piece of sourdough toast. Avocados are so irresistible they unite football fans and hipsters.

The environmental consequences of this green gold fever have been far-reaching. “One of the greatest signs of this drastic alteration has been the zoning changes,” notes a report in Gatopardo. “Land and forests have been legally—and sometimes illegally—transformed into areas dedicated to avocado cultivation. The environmental cost of this change is enormous: one avocado tree consumes enough water for eight pine trees.” Analysis by researcher Dr. Benjamín Revuelta at the Universidad Michoacana concludes that up to 80% of avocado farms in Michoacán lack proper environmental permits.

When I gleefully slather avocado on toast, I am reminded of Wendell Berry’s words: “eating is an agricultural act.” No consumption is innocent in our modern world, free from consequences for the land and the people providing for our needs and yes, our desires. As Berry observed: “we learn from our gardens to deal with the most urgent question of the time: how much is enough?”

Journalists: Witnesses and Victims

Published on The Mexpatriate blog on Mar. 4, 2013

A grainy video flickers on the white screen in front of you; you can tell it was taken at night, the faces have a greenish cast to them as if you're looking at them through night vision goggles. It's somewhere in the desert and it's cold. The young man wearing a baseball cap shivers and rubs his arms as he chats with the others. They are all waiting for someone to arrive. The young man is smiling, a quick laugh escapes, then fast banter—he’s nervous. Suddenly, you're nervous too. You feel it first deep in your gut and then it flutters up to your chest, your throat. Something terrible is about to happen. I can hardly keep watching now that I know; I want these guys to stop talking, stop huddling against the cold wind, stop waiting for the approaching horror. Please hurry up, fast forward through the dread. Finally a pick-up truck arrives and turns off its headlights. The man in the baseball cap tentatively move towards it, the camera stays behind. And then it all moves so fast - someone steps out of the truck, the guy waves to him, someone else yells and the guy's hands go up in the air. Shots ring out.

I watched this scene play out at Teatro El Milagro in Mexico City last month, during a gripping performance of Iluminaciones VII by award-winning playwright Hugo Alfredo Hinojosa, directed by the innovative Alonso Barrera. The play does not follow a chronological sequence of events, but rather fragments of experiences surrounding the murder of a journalist by drug traffickers (the young man in the baseball cap). There is only one way I can describe what it's like to watch Iluminaciones VII: imagine yourself in a waking nightmare. The characters are stylized, sometimes moving in slow motion; the scenes are surreal; the images are disconcerting; and the one constant is a suffocating sense of dread. At the end of the play, the dead journalist comes upon his murderer in purgatory; the hit man seems numb to the violence that extinguished both of their lives and concludes that after all, they both died on the job.

The cartels have become intimidation experts who in some states, like Zacatecas, "haven't had to kill a single journalist to silence every journalist", according to an in-depth February report by Mike O'Connor from the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Of course, journalism shouldn’t be as hazardous a career path as assassin for a drug cartel, but sadly, a look at Mexico today would suggest otherwise. “Mexico continues to be the western hemisphere’s deadliest country for media personnel. More than 100 journalists have been murdered or have disappeared in the past decade...In the immense majority of cases, journalists are killed by drug cartels for covering their activities. The police and judicial investigations into these murders are often closed quickly or are paralyzed by cumbersome bureaucratic procedures. The result is almost total impunity.”

This is an excerpt from a Reporters without Borders document of recommendations submitted to the UN Human Rights Council today, coming on the heels of the murder of a journalist in Chihuahua yesterday and last week’s armed attacks on the offices of the El Siglo de Torreón newspaper. Jaime Guadalupe Domínguez, the director of a news website called Ojinaga Noticias, was shot 18 times yesterday in Ojinaga, Chihuahua, the first journalist to be killed during President Peña Nieto's term. Domínguez's colleagues posted the details of the reporter’s death—including the fact that the murderers stole his camera after killing him—and said it would be their last story. The website has since been taken down.

During the week of its 91st anniversary, the El Siglo de Torreón newspaper offices experienced three armed attacks by assailants using AK-47s and other assault weapons, leaving one police officer injured and a bystander dead. “[We] celebrate our 91 years in the midst of one of the worst waves of violence ever unleashed against us in our long life. In the last three days, the offices of this publication have suffered attacks against the federal police who provide security for this building. It hasn’t even been a month since five of our colleagues were kidnapped in an effort to intimidate us...Intimidation of the press is an attack on the entire community we serve and inform.”

The cartels have become intimidation experts who in some states, like Zacatecas, “haven't had to kill a single journalist to silence every journalist”, according to an in-depth February report by Mike O’Connor from the Committee to Protect Journalists. “According to CPJ research, this is the pattern now in many Mexican states: Cartels gain control, the press is intimidated, and the public is uninformed. And since there are no deaths among local journalists, there is no attention drawn to the pervasive problem of self-censorship.” O’Connor goes on to relate the stories of anguished and frustrated journalists who have stopped reporting on the takeover of their state by the Zetas. In the words of one female reporter: “We have failed the people here who counted on us to tell them what was happening all around us. We had the responsibility to tell them, but we could not. So we failed them.”

O’Connor poses an important question in his analysis of the unspoken troubles of Zacatecas: “how many other, seemingly quiet states are really just like Zacatecas?”

Sources

1.

Amenazas de muerte y más de 50 millones de dólares en pérdidas: la semana negra del aguacate mexicano (El País México)

AMLO acusa intereses económicos tras suspensión de entrada de aguacate michoacano a EU (Animal Político)

¿Por qué Estados Unidos bloqueó nuestras exportaciones de aguacate? (El Financiero)

México reanuda exportación de aguacates a Estados Unidos (Animal Político)

La fiebre del aguacate. El fruto de la discordia en Michoacán (Gatopardo)

El dilema del consumo del aguacate (Animal Político)

El aguacate que todos queremos…hasta el narco (Opinión 51)

Casi 3000 millones de dólares y 300,000 empleos en riesgo por la prohibición de EE UU a los aguacates mexicanos (El País México)

2.

Atacar a los medios es atacar a la comunidad (Animal Político)

Attacks on the press: Mexican self-censorship takes root (Committee to Protect Journalists)