La Semana: Sunday, July 17

The week in US-Mexico relations and the story of a contested historical artifact

Welcome to the Sunday edition of The Mexpatriate.

In tonight’s newsletter:

The US-Mexico Relationship: It’s Complicated

The Saga of the “Penacho” of Moctezuma

Please share your comments, feedback and questions, and feel free to forward this to anyone who may be interested. You will find all sources linked to directly in the body of the text.

El Cotorreo…

“…Instead of showing a commitment to combat the corruption of the past, or the present, [this investigation] has a political and electoral purpose; to again strike at Peña Nieto as Morena’s political piñata, who holds many votes hidden inside.”

—Adela Navarro (Opinión 51) on the investigation into former president Peña Nieto

*Caro Quintero is arrested*

And the “Narcos” screenwriters:

The US-Mexico Relationship: It’s Complicated

“I know your opponents, the conservatives, will hit the roof, but without a bold development and welfare program it will not be possible to solve problems or gain the people’s support. The way out of this crisis is not conservatism, but transformation.”

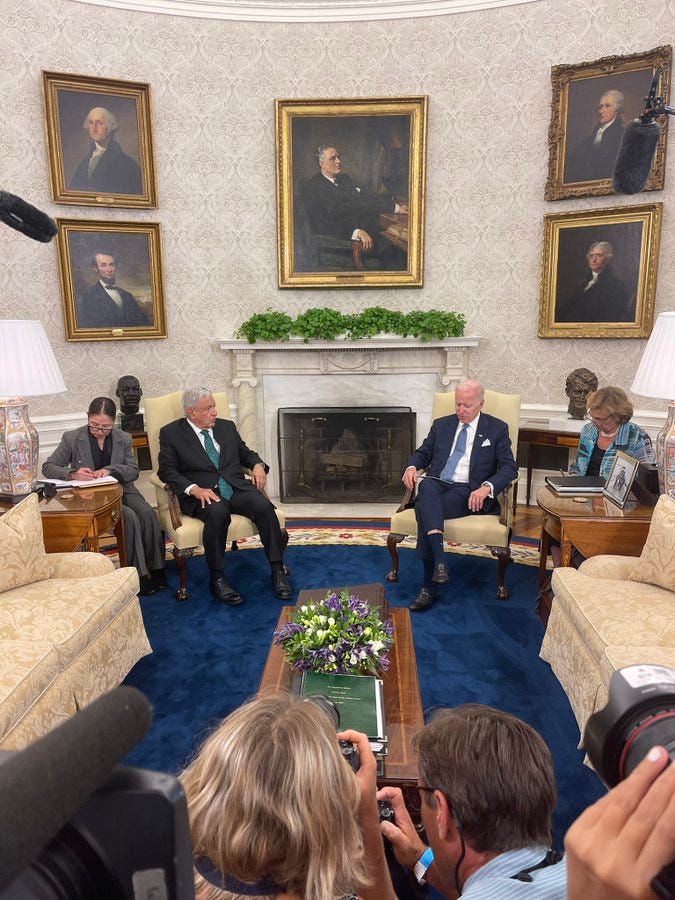

In President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s 31-minute monologue in the Oval Office on July 12—described with tongue in cheek as a “filibuster” by Jorge Castañeda—he touched on economic cooperation and immigration policy, sprinkled with this free advice to President Joe Biden. It must have stung, as Biden faces poor approval ratings, a stalled agenda and a stormy outlook for midterm elections. After the visit concluded and agreements were duly released to the press, the jibes continued in the schoolyard of international diplomacy: a White House official gloat-tweeted that “Trump in his four years couldn’t finish a border wall, let alone get Mexico to pay for it” in reference to the $1.5 billion dollars Mexico promised to invest in “border infrastructure” by 2024.

Behind the bluster, what is the real status of the US-Mexico relationship? What were the tangible outcomes of this bilateral encounter? The most significant topics on the agenda were immigration policy, energy/climate change and drug trafficking, particularly the production of fentanyl in Mexico. The tangible takeaways were minimal, but many observers viewed the purpose of this relatively informal visit as reassurance after recent tense moments in the relationship—and an opportunity for political posturing to promote each president’s domestic agenda.

In the weeks leading up to AMLO’s arrival in Washington, there have been some noisy tiffs: first, his decision to not attend the Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles in June as an expression of solidarity with the leaders of Nicaragua, Venezuela and Cuba, who were not invited. Secretary of Foreign Relations, Marcelo Ebrard, attended in his place. Then on July 5, a New York Times article titled “Has Biden’s Top Diplomat in Mexico Gone Too Far, Officials Ask?” put ambassador Ken Salazar in the spotlight, implying that he is too chummy with the Mexican president and “has caused confusion about the U.S. position on some of the most sensitive policy issues.” Concretely, the reporters reference Salazar’s public skepticism of the outcome of the 2006 Mexican presidential election, which López Obrador lost in a photo-finish to Felipe Calderón. While speculation about the contest is hardly news—the results sparked a national political crisis—it is surprising that Salazar wouldn’t comprehend the diplomatic implications of his statements about the legitimacy of an election that the U.S. officially recognized.

In the same vein, Salazar appears to favor less formal channels in his communication with López Obrador, which makes the State Department anxious. However, considering AMLO’s own style and lack of interest in diplomatic protocols or etiquette, it could be argued that Salazar is merely trying to increase his influence over the Mexican president by doing the same. “Perhaps the main problem is less the ambassador and more the way that the internal politics of each country is influencing the bilateral relationship,” observes journalist Carlos Bravo Regidor.

More broadly, the question of Salazar’s fitness as ambassador and his management of AMLO is harder to answer with any strong evidence. While there have been some awkward moments in the public relationship between Biden and AMLO—spurred partly by U.S. objections to AMLO’s domestic policy and the latter’s defense of targets of the U.S. government, like Julian Assange—the reality is that Mexico continues to comply with the fundamental U.S. policy objectives on migration control and the drug war. In their joint press statement, the White House and López Obrador announced their commitment to “establish a U.S.-Mexico operational task force to disrupt the flow of fentanyl into our countries” along with continued “robust operational efforts” between the countries’ law enforcement agencies.

In what was either a timely coincidence or something less serendipitous, one of the DEA’s most wanted drug kingpins, the “narco of narcos” (even on Netflix), Rafael Caro Quintero (69), was captured by Mexican armed forces on July 15. This is the highest profile drug arrest during AMLO’s sexenio and Caro Quintero’s extradition is expected to come swiftly, making it a “win” for both administrations—though it was marred by the crash shortly afterwards of a Black Hawk helicopter that killed 14 of the Mexican marines who participated in the operation. No cause has yet been identified.

Meanwhile, on the immigration front: “López Obrador has announced that he will use the meeting to advocate for greater access for migrants to employment opportunities in the United States. Mexico’s Minister of the Interior even stated in June that he expects the bilateral meeting to include the announcement of up to 300,000 temporary U.S. work visas, including some 150,000 for migrants coming from Mexico,” noted an article published on July 11 by the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA). However, while Biden did mention the 300,000 H-2 work visas issued last year to Mexican workers, his only specific future commitment was to double those issued to Central Americans, not Mexicans, in this fiscal year. AMLO agreed to the $1.5 billion dollar Mexican investment in improved “smart” border technology, and tacitly, to continue to function as the “wall” between Central America and the United States.

Energy policy has been an uncomfortable topic between the two countries during AMLO’s term. The Mexican president’s crusade to reverse privatization in the Mexican energy market, which increases reliance on “dirtier” sources of energy, has unnerved both investors and clean energy advocates. While López Obrador’s controversial electricity reform bill didn’t make it through Congress, there are still significant breaches in the bilateral agenda.

In June, López Obrador presented a 10-point policy agenda—perhaps better described as a wishlist—to address climate change that left progressive energy analysts disappointed, to put it mildly. “Two of the proposed measures are particularly concerning given that they focus on promoting the production of gasoline and diesel by Pemex to meet domestic demand and reduce Mexico’s dependence on imports (mainly from the U.S.): the unfinished “Olmeca” refinery in Dos Bocas, Tabasco, and the construction of two coker units to process fuel oil in the Tula and Salina Cruz refineries.” The agenda also reiterates the commitment to generate 35% of the country’s electricity from renewable sources by 2024, but the Ministry of Energy has already acknowledged this deadline cannot be met until 2031.

At the July 12 meeting, AMLO stated: “we reaffirm our commitment that U.S. citizens who want to buy gasoline at Mexican gas stations along the border can do so, we will not close the border to them, and they can pay less.” Gasoline has been subsidized by the administration, maintaining an artificially lower price, but the president of course didn’t address the sticky situation of Mexican taxpayers’ financing of cheap fuel. The data released by the government for this year, up to the second week of June, indicated public financial losses of 176 billion pesos as a result of the subsidies.

This month also marks two years since the USMCA (US-Mexico-Canada Agreement) free trade treaty came into effect, replacing NAFTA. While think tanks and business leaders concur that the agreement has had positive economic impact (trade has increased on average 6% across the region from 2019-21), there are grumbles from both sides of the border that could threaten its survival in the 2025-26 review. “For a good review of USMCA, one needs comprehensive metrics, serious deliberation, and effective ‘public diplomacy’ to help assure that Americans, Canadians and Mexicans are well informed about progress and what is at stake,” notes a report from The Mexico Institute.

Based on recent events, it seems that “serious deliberation” and “effective public diplomacy” may be in short supply in the near future.

The Saga of the “Penacho” of Moctezuma

The July edition of Letras Libres magazine focuses on the theme “Legacies of Colonialism”, and includes an essay about the strikingly beautiful, and controversial, “penacho” (crest or headdress) of Moctezuma. This historical artifact—a piece of “dynamic artisanal engineering” made from hundreds of feathers from four different bird species and 1,554 metallic adornments, most of them gold—has made the news several times this year alone, but has a much longer history of inspiring polemic debate. It is today part of the collection of the Weltmuseum Wien in Vienna, Austria, where it has been housed since 1889. However, the “penacho” (or “quetzalapanecáyotl” in Náhuatl) has been in Europe far longer; it was first mentioned as part of the estate of Archduke Ferdinand II of Tyrol in 1596. Several of Mexico’s presidents (including López Obrador) have requested the return of the artifact to Mexico, and there was even a purported attempt by the Hapsburg Emperor of Mexico, Maximilian, to have the piece brought back to its land of origin. Austrian diplomats and curators have refused to lend or return the object to Mexico based on two arguments, first that it was a gift, second (and more convincingly), that it is too fragile to transport safely.

As is the case with many historical artifacts, what we know about the “headdress of Moctezuma” is shrouded in mystery, half-truths and speculation: to start, it may not have been used as a headdress, and it is unclear if it was used by Moctezuma. The piece may have been a ceremonial adornment that was given to Hernán Cortés by the tlatoani (ruler) of the Mexica, or it may have been stolen by the conquistador and sent, with other treasures, along with one of his missives to King Carlos V. We do know that many Mesoamerican cultures, including the Aztecs, were masters of feather mosaic art (“plumaria”) and regarded feathers as important symbols in military and religious ceremonies. “The feathers cannot be separated from the animal they came from, and thus the pairing of bird-feather defines their symbolic nature. The selection of feathers from certain birds, combined with other reflective materials, such as polished stones, pearls, shells and gold, were all part of the iconography and customs for each occasion,” explains the Mexican historian, María Olvido Moreno Guzmán, who was part of the most recent joint Mexican-Austrian “penacho” restoration team.

The splendor of this ancient masterpiece, and the powerful symbolism it embodies, brings a swell of questions to mind: of myth versus history, nationalism versus rationalism and of the colonial legacy in the New World. After all, the “mystification of the continent began with Columbus himself.” Does the modern state of Mexico, born in 1821—three hundred years after the fall of Tenochtitlan—have the right to inherit this treasure from the Mexica empire? “To suggest that there is continuity from the owners of the ‘penacho’ in the 16th century to the contemporary Mexican state is to normalize a type of racial essentialism produced by not only blurring the ethnic and racial diversity of Mexico, but also marginalizing certain groups in this mix,” notes the essay in Letras Libres. There is also the question of taking political advantage of the transcendent symbolism of this one object while ignoring so much more of the archaeological heritage of Mexico. As writer Rodrigo Flores Sánchez notes, “in Mexico we have not distinguished ourselves in respecting our natural, historical and cultural heritage.” The federal budget for culture has been slashed by this administration.

I saw a replica of the “penacho” on a visit last year to the “Grandeza de México” exhibit at the Museo Nacional de la Antropología in Mexico City. This piece was commissioned in 1938 by ex-president Abelardo Rodríguez and made by a feather mosaic artist (named Francisco Moctezuma) in conjunction with historians, archaeologists and biologists. It is magnificent. And I confess to a tinge of disappointment when I saw the word “replica”, clouding my initial awe. Why? This “penacho” is no less iridescent in brilliance, no less a work of art, juxtaposing power and fragility. Perhaps our human yearning for connection with the past, for an intangible spirit long gone, sparks this desire for authenticity, to be physically in the presence of something real.

Which brings me to one more question: what do museums mean to us today? We are no less obsessed with curating curiosities (what else is Instagram?) but we can “see” and “collect” so much—everything we could imagine—in the internet emporium. What then is the value of visiting and gawking at art and artifacts “IRL”*? Maybe an answer lies within the centuries of Austrian and Mexican dedication to the possession, preservation and display of this living fragment of a distant history.

*in real life

Excellent articles! Your phrasing, expression and depth/sensitivity is unique, refreshing and remarkable. Thank you!