La Semana: Sunday, July 3

The week in academics vs the 4T and the debate over a "pax narca"

Welcome to the Sunday edition of The Mexpatriate.

In today’s newsletter:

“Neoliberals” vs “The People”: Polarization in Mexican Academia

“Pax narca”: Pragmatism or Fantasy?

I’ve decided to add a new section called El Cotorreo (“the chatter”), a selection of topical quotes or tweets of the week—a snapshot of the national conversation.

Please share your comments, feedback and questions, and feel free to forward this to anyone who may be interested. You will find all sources linked to directly in the body of the text.

El Cotorreo…

“What do the priests want? For us to solve problems using violence?”

—President López Obrador in response to criticism of his security policy from Jesuit priests

“I wonder if the President has gone from being the highest authority on security to a mere spectator.”

—Denise Maerker (journalist) on the president’s remarks about national security

“Don’t invite Movimiento Ciudadano to get on board the Titanic.”

—Dante Delgado (president of the Movimiento Ciudadano party) in reference to joining the PAN-PRI-PRD coalition in 2024

“Neoliberals” vs “The People”: Polarization in Mexican Academia

“We state our deep concern for the state of higher education and scientific research in Mexico. We observe that in addition to structural problems suffered for many years, there is now the open persecution of faculty freedom, the proprietary use of university assets and research centers, the budgetary suffocation for political objectives, and in general, the prevalence of biased interests above educational ones.”

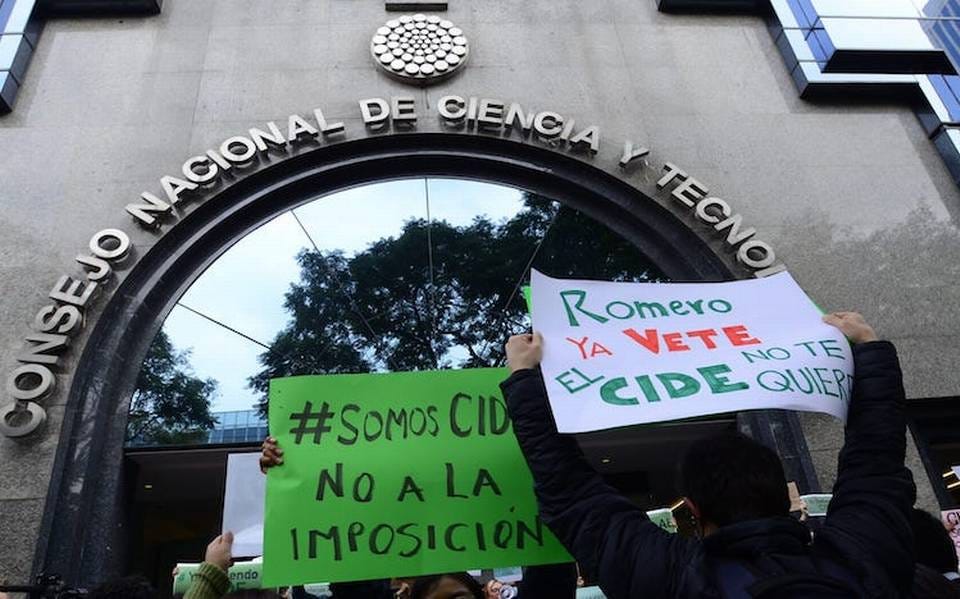

This is from a statement issued by students and faculty at the CIDE (Center for Research and Teaching in Economics) last month as part of their protests demanding the resignation of the head of the CONACYT (National Council for Science and Technology), as well as the CIDE’s current director, José Antonio Romero Telleache, whom they fear will dismantle their institution from the inside out. The protestors marched from Bellas Artes to the Palacio Nacional in Mexico City on June 4 and tried to deliver their statement directly to the president (unsuccessfully). In November last year, students staged a takeover of the campus to protest the appointment of Romero as director without adherence to the university’s bylaws. In September 2021, the FGR (Attorney General’s Office) tried to obtain warrants for the arrest of 31 scientific and academic researchers on charges including organized crime and embezzlement, which if carried out, would mean automatic pre-trial detention at a high security prison.

Suddenly all the outraged spats echoing through “ivory towers” and in Twitter threads in the U.S. seem somewhat staid in comparison. In an inversion of the “culture wars” waged up north, the epithet of “elitist” is directed here towards those perceived to be “empreacadémicos”—business-academics—hailing from the right side of the political spectrum, not the left. President López Obrador has repeatedly characterized the CIDE, which was founded as a public university in 1974, as hijacked by “neoliberals” with “retrograde” and “conservative” regulations that protect private interests at the expense of the public good.

“Without its own funding, the CIDE is doubly impacted by ‘national austerity’…17 million pesos are owed to around 100 people (academics and administrators) for work performed from 2019-2021,” laments a member of the faculty of the history department, Jean Meyer, in an article published by Letras Libres. “We couldn’t offer continuing education diplomas in the 2020-22 school year. Since December 2021, fifteen research professors have left to work at other institutions or abroad. Others will follow.”

Funding—the allotment, administration, or abuse of it—is the central conflict in this drama. According to the FGR, there has been systematic, nefarious misuse of public monies through a civil association (AC) created in 2002, the Foro Consultivo Científico y Tecnológico (FORO) which received funding on behalf of the CONACYT. While the attorney general’s office has failed to convince a judge to issue warrants for the arrest of the 31 accused academics, the ethical use of public funds has been called into question by others too. In an investigative report published by Poder LATAM called “The Science Mafia” in 2020, the journalist Ricardo Balderas exposed inappropriate personal expenses and high salaries earned by “prestigious academics [who] have benefited personally from public funding for the development of science and technology in Mexico.”

On June 28, María Elena Álvarez-Buylla, director of the CONACYT, announced that grants would be restricted to subject areas deemed useful for the public sector, at the discretion of her agency and the Public Education Department (SEP). In this sexenio, funding for research in the sciences and humanities has dropped by 56%. The biologist, who was appointed by AMLO in 2018, has told students at the CIDE that they are “opposing the transformation of Mexico”. AMLO’s suspicious view of universities is nothing new: “A close reading of his speeches since 2018 shows he considers them to be the principal architects and beneficiaries of the neoliberal economic reforms enacted by governments since 1982,” explains Catherine Andrews, a faculty member of CIDE who was laid off in the recent “purges” of the faculty. “For López Obrador, academic life is one of undeserved privileges, huge financial rewards (gained from working on projects for private companies), and little relevant service to the public good.”

The jumble of biased interests in this feud is hard to untangle—the accusers have also been accused of taking advantage of their positions for personal gain. The attorney general, Alejandro Gertz Manero, had previously been rejected five times in his attempts to obtain the status of “Level III” in the Sistema Nacional de Investigadores (National System of Researchers) of CONACYT, but after eleven years of attempts, in June 2021, his application was approved.

“Everyone has taken a position, few have a thorough understanding of the problem and each side wants their position to win since it’s become an issue of prestige,” notes José Ramón Cosío, academic and associate justice of the Supreme Court of Mexico. The bid of the cuarta transformación against higher education institutions has cost AMLO popularity amongst a particular demographic: according to one poll, 65% of people with a college degree surveyed in February 2019 approved of the president, and by November 2021, that percentage had dropped to only 8%.

As described in an essay written by professor Ernesto Mendoza: “What the promoters of the 4T seek is the over-simplification that makes it legitimate to attack anyone who is critical or opposes their program; without accounting for the vast differences amongst them or the diversity of their causes (feminists, human rights defenders, journalists, critics of militarization, indigenous rights defenders, communities opposed to mega-projects, and defenders of critical thinking), all of them are ‘neoliberals.’”

It is hard to ignore the glint of irony: a government that purports to represent the will of the people against corruption is intent on prosecuting academics while violent crimes go unpunished in 94% of cases, and appears to abdicate responsibility to pursue justice.

See below…

“Pax narca”: Pragmatism or Fantasy?

“There are places where there is a strong gang and there aren’t confrontations—Sinaloa is not one of the states with the most homicides.” In a mañanera press conference on June 15, President López Obrador ruminated aloud about the benefits of a so-called “pax narca”. He claimed that 75% of murders are caused by rivalry between gangs (though it is unclear where this statistic comes from) and used the example of conflict in Michoacán to further his argument: “here there isn’t just one group, there are around 10 different groups.”

Researchers and analysts don’t disagree with the president on his observations, even if they seem oddly detached coming from the person in charge of Mexico’s security strategy for the past four years. There are a number of examples of peaks and troughs of homicide rates in areas that are disputed—and then won—by one group exterminating the others. However, as pointed out in an opinion piece by researcher Carlos Matienzo, the murder rate in Sinaloa is still 3 times the global average. Matienzo also clarifies that the other popular notion of a “pax narca”—the idea that tacit agreements made between a centralized government, as exemplified by the 20th-century PRI, with criminal groups was more stable—is more myth than history. “The country wasn’t as peaceful as is popularly believed, nor were the political-criminal agreements as stable. The priista regime was not as centralized as assumed. The local caciques did have power and political disputes often set off criminal violence.”

The headlines that shook the country in the last two weeks seem to highlight the limitations of AMLO’s assessment. On June 14, sections of the city of San Cristóbal de las Casas were at the mercy of a heavily armed group of about 100 men who took over the streets and fired into the air. In what appears to have been an intimidation tactic to ensure local merchants comply with paying the “derecho de piso”, there was one death and a lot of panic. The municipal police did not intervene—the mayor admitted to being outgunned—and a contingent of the Guardia Nacional (National Guard) arrived four hours after the incident. In another story that demonstrated the consequences of a hands-off law enforcement strategy, a known criminal who has been terrorizing his homeland in the Sierra Tarahumara of Chihuahua for years, murdered two Jesuit priests and a tour guide who had run into their church in Cerocahui to seek refuge. The motive appears to have been a baseball game that didn’t go “El Chueco’s” way the weekend before.

“From this holy sanctuary, a space of reconciliation, of peace and of hope, we respectfully ask, Mr. President, that you reconsider your public security plan, because we are not doing well and this is a public outcry,” said Padre Javier “El Pato” Ávila at the funeral service. “The hugs aren’t enough to cover the bullet wounds.”

Some have speculated this could be a watershed moment in the sexenio, a rallying cry analogous to the disappearance of 43 students in Ayotzinapa in 2014, during the presidency of Enrique Peña Nieto. But while a distraught public is pained by these incidents, there has been little indication of a change of course in policy. “I don’t think this will change the government policy…the feeling I have is that there is a validation of the power of criminals in large territories of the country, but there is no assumption of responsibility to end this, no reflection on what has gone wrong in the last four years,” noted journalist Denise Maerker.

Is there an alternative “pax narca”? Or better still, just “pax”? Alejandro Moreno, president of the PRI (Partido Revolucionario Institucional) made a statement last week that his party will advocate for relaxing gun regulations to make it easier for citizens to arm themselves. Will this win the embattled PRI a few votes? Perhaps. But for those more interested in solutions than slogans, there is a less flashy—and dangerous— answer: rule of law.

In “Dreamland”, a fascinating investigation into the opiate crisis as it played out on both sides of the border, Sam Quinones describes how the “Xalisco boys”, as they became known to DEA agents, successfully spread black tar heroin to cities that had never seen it before by delivering the drug “like pizza”. One of the keys to their success was avoiding violence. “Shootouts were unthinkable. Violence brought police attention; guns earned long prison time.” In other words, law enforcement made conflict bad for business. There is no doubt that this kind of “pax narca” is also haunted by death: the overdose numbers are numbing in scale. But there is an element of coexistence—the kind maybe alluded to by the president—only made possible by the state monopoly on violence, the consistent enforcement of law.