La Semana: Sunday, July 31

The week in government transparency and complaints about "expats"

Welcome to the Sunday edition of The Mexpatriate.

In today’s newsletter:

How accessible is public information in Mexico?

Expat vs immigrant: A personal essay

Please share your comments, feedback and questions, and feel free to forward this to anyone who may be interested. You will find all sources linked to directly in the body of the text.

El Cotorreo…

AMLO announces his government will go from “republican austerity” to “Franciscan poverty”.

Sir, the problem is not the ink cartridges for the civil registry office, it’s that the Tren Maya is going to cost 10% of the country’s external debt.

How accessible is public information in Mexico?

“Facing the public is a sign of openness, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that citizen requests are honored…I think they are confusing the communicativeness of the government—the daily press conferences—with access to information.” In an interview last week, Eduardo Bohórquez (director of Transparencia Mexicana) assessed the current administration’s track record on access to information, in light of the crash of CompraNet, the electronic system for government expenditures that has operated continuously since 1996. Until July 15, 2022.

“We hereby inform that due to reasons beyond the control of this agency and the management of the CompraNet platform, starting at 16:00 hours on Friday, July 15 2022, there were technical errors in the infrastructure that hosts said platform, limiting its operations. For the aforementioned reasons, CompraNet is temporarily suspended until further notice,” read a statement put out by the government on July 18. The Department of the Treasury (SHCP) has since stated that they expect the system to resume operations by the second week of August. Meanwhile, according to estimates made by think tank Mexicanos Contra la Corrupción (Mexicans Against Corruption), the government has made expenditures of as much as 60 billion pesos since the crash, based on average daily federal spending this year. “Opacity is the gateway for corruption. We know that government purchases are always sensitive and require maximum openness and maximum oversight,” notes University of Guadalajara professor and researcher Lourdes Morales. “With the platform offline, purchasing is happening as it did 30 years ago: in offices, with officials making decisions without any external supervision and probably without the presence of all elegible competitors,” according to an article in Animal Político.

The same week that CompraNet went offline, the PNT (National Transparency Platform) was the victim of 50 million cyberattacks or hacking attempts (from July 11-13). The attacks—caused by robotic fake submissions—were designed to cause a slowdown of the system and according to the INAI (National Institute for Transparency, Access to Information and Personal Data Protection) cybersecurity team, have been traced to foreign IP addresses.

It may come as a surprise—it did to me—that Mexico has a rigorous legal framework for public access to information. In fact, according to the Global Right to Information Rating, Mexico scores higher than the USA, Canada or the United Kingdom. Interestingly, so does India, which seems to signal that this ranking is detached from corruption indices, and that transparency can only go so far on its own.

The INAI was formed in 2002 and granted autonomy and ability to make legally binding resolutions in 2013. Prior to that, “getting data or a file to put together a story depended on the relationships reporters had with government sources…sometimes the scenes were surreal as public officials ‘leaked’ information that was delivered in suspicious packages…as if it was contraband,” explains journalist Sandra Romandía.

Today the INAI, through the PNT, provides a robust and moderately user-friendly system for reviewing public data and submitting requests. In comparison, the US FOIA (Freedom of Information Act) sites do seem outdated—“most federal agencies now accept FOIA requests electronically, including by web form, e-mail or fax”—and offer citizens response times of up to 280 working days. The INAI usually meets its legal obligation to respond to requests within 20 working days.

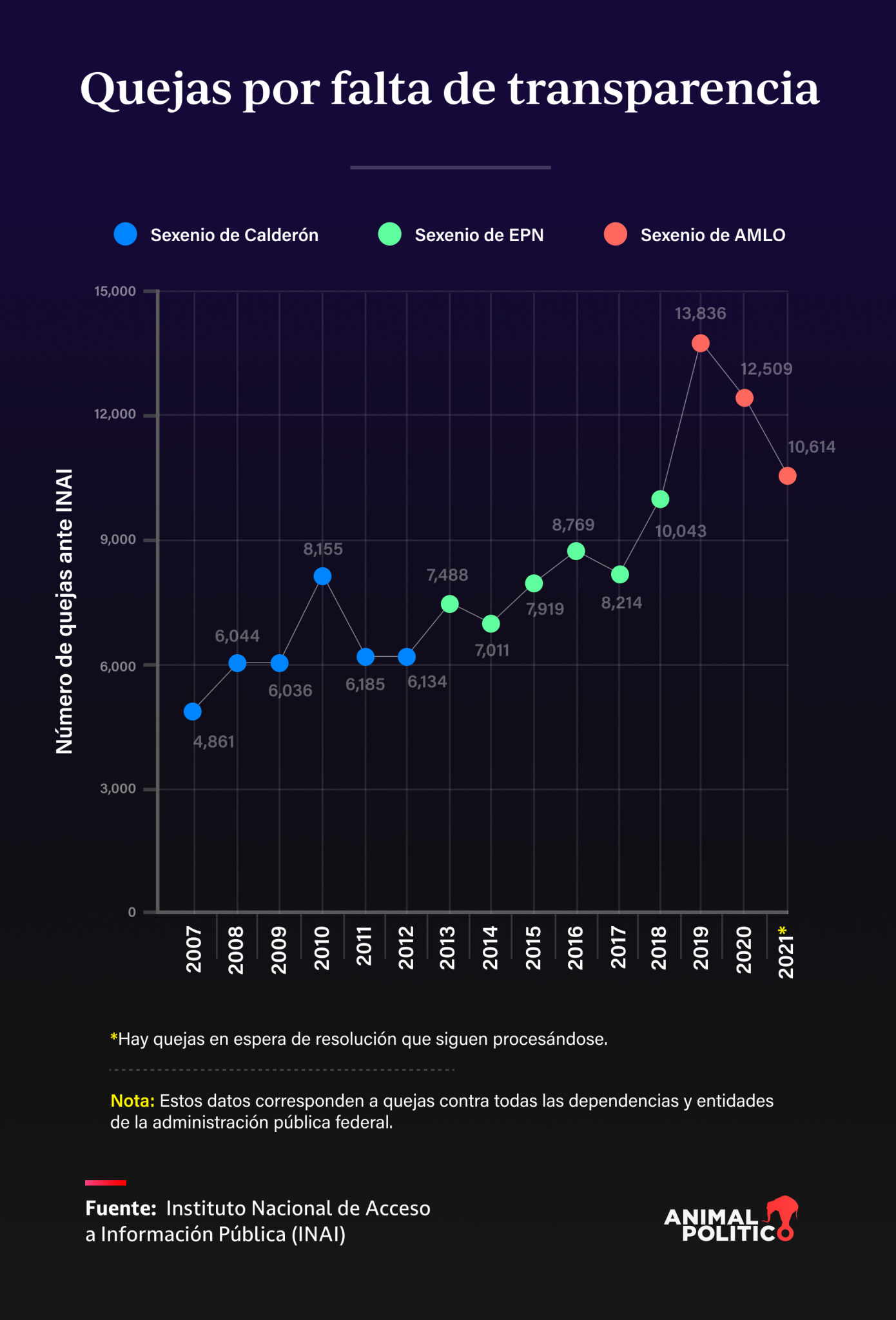

The agency hasn’t been exempt from controversy. In addition to providing access to public data, its mandate includes protecting individuals’ personal data and its use. There was a case in 2015 when the INAI ruled in favor of a magnate who had requested that Google remove three search results that contained negative information about his family’s business interests. Google appealed the ruling and won. Like many government institutions, the INAI has also come under attack from the current administration. In January 2019, President López Obrador proposed the dissolution of the agency and its absorption into the Secretaría de Funciones Públicas (Department of Public Services), which reports to the executive. AMLO and the INAI have been at odds ever since. This administration has had the highest annual registration of citizen complaints to INAI for lack of transparency in federal institutions. In November 2021, AMLO claimed the agency had been a costly sham for years, and that “now they (INAI) are very demanding, but we have nothing to hide, there is complete, utter transparency, because it is one of the golden rules of democracy. What would we have to hide? Nothing.”

Expat vs immigrant: A personal essay

We all have identities that overlay one another: family, culture, country, political party, Mac or PC. We inherit and collect identities as tools to help us understand the world and our place in it. As a self-described “mexpatriate”, I’ve spent a lot of time pondering what it means to not quite belong in one place or the other, to be forever in the space between.

There has been a recent flurry of articles about the influx of “digital nomads” moving to Mexico City since 2020 and how they have impacted particular colonias, bringing inflated rents, signs and menus in English, and the sting of accelerated gentrification. Of course, this experience is hardly unique to Mexico City: cities all over the world grapple with the fallout from the Airbnb effect, and the widening gap between the privileges of the remote worker and the pressures on the “essential” worker. What strikes me in these expressions of frustration is that not even financial advantage can protect these “expats” from that age-old woe of the immigrant: being unwanted.

Back in 2015, I wrote an essay about this topic and how language influences—and is influenced by—our chosen identities. To me, by using the word “expatriate”, we might erase points of commonality, distancing ourselves from the act of migration. The movement of people across borders. Perhaps this aspirational word choice gets to the heart of why locals grumble about newcomers who seem utterly disconnected from the places they choose to inhabit?

I hope you enjoy the piece and I look forward to your comments.

I recently came across an article in the “Expat” section of the Wall Street Journal—for “global nomads everywhere” (with Wifi, of course)—titled “What makes the expat lifestyle so addictive?” And then I wondered: what if you swapped out “expat” for “immigrant”?

The article touches on the notoriety developed by some expatriates—“hooked on domestic helpers and padded salaries”—but concludes that the “drug” that keeps these jet-setters coming back for more is actually a “distilled sense of oneself in relationship to the world.” They’re finding themselves by leaving; whatever motivated them to venture out in the first place, their discovery is an internal, personal one. As described by one of the article’s subjects: “As an expat, I have the ability to live in a foreign country and just be left alone to do.”

I picture José Fernando Pérez. He’s my babysitter’s husband and he just returned to Mexico a few days ago after an “expatriate” experience in the U.S. He was imprisoned for four months after he was caught crossing the border near Eagle Pass, Texas.

Of course, we wouldn’t refer to José as an expatriate. He was an (attempted) undocumented immigrant. The difference between these words and the concepts and identities they represent is the difference between night and day, black and white, wanted and unwanted. The word “expatriate” conjures visions of adventure, sophistication, exoticism. “Immigrant” more likely brings to mind struggle, poverty, obscurity.

“So what?” you might say. Synonyms don’t always have the same layers of meaning under the surface. For example, “traveler” and “tourist”, “housewife” and “stay-at-home mother”, “exotic dancer” and “stripper”. There lies the beauty of language. But it’s good to shake up words sometimes, dump out the contents. Think, reflect, maybe even redefine. It also just so happens that I have a personal interest here since I find myself in the “expatriate” category.

So, how do the actual definitions of these words differ? According to the Oxford Dictionary, not much. An expatriate is “someone who lives outside his or her native country” and an immigrant is “a person who comes to live permanently in a foreign country.” Depends on whether you’re coming or going I guess. But technically, we’re American immigrants in Mexico and they’re Mexican expatriates in the USA. Same difference. But expatriates don’t usually find themselves arriving at their destinations in truckloads, or swimming, while immigrants all over the world, from Laredo to Calais, might.

The word “expatriate” can also refer to someone who was exiled or banished from his or her homeland. Even now, living in an “expat” community and often meeting new arrivals, there is a shared sense that more than a few of us were running away when we landed here. What do you think, is that guy really a retired travel agent, or a fugitive con artist? Expatriates are often distinguished by their capacity for reinvention. Their identities are fluid; perhaps that’s what inspired their wanderings in the first place. Or it happened along the way. Even that ancient expatriate, Herodotus, the wandering father of history himself, was apparently more pushed than pulled to travel beyond his homeland. An epitaph at one of his possible gravesites reads:

Herodotus, the son of Sphynx

Lies; in Ionic history without peer;

A Dorian born, who fled from Slander’s brand

And made in Thuria his new native land

Historically, American expatriates have been associated with bohemian lifestyles, artistic enclaves, a lot of alcohol, torrid affairs, and political agitation. “You hang around cafés,” in the words of that quintessential literary expat, Ernest Hemingway. Describes my life, for sure. The Brits have their own long and storied expatriate past, “living abroad” on many continents, perfecting the art of managing native staff and inspiring rebellions.

Admittedly, even those who aren’t imbibing the “heady cocktail of money, status and adrenaline” as described in the WSJ article can be a bit insufferable, managing to annoy people in two countries at once. There are those sun-drenched Facebook photos posted while friends and family are being sucked through the polar vortex. The cost of living comparisons: “Just got my fillings fixed, teeth whitened, face lifted and chin tucked for the same cost as a haircut back home! Bought a gallon of fresh squeezed orange juice on my way back to the villa - only set me back 2 dollars!” I might exaggerate. Slightly.

Here in the adoptive country, their communication skills are often lacking and their cultural sensitivity is out of tune. But at least in Mexico, expats are usually tolerated with considerable patience, even affection. And of course, many of them create businesses, found charities and enrich communities.

I am a foreigner living in Mexico but as I look around me, I see double; as an outsider and an insider, a stranger and a friend. I am an expatriate, and also an immigrant. My family has roots here. My grandfather moved his wife and two toddling girls from Minnesota to Mexico City in 1960, back when it was a city of somewhat imaginable size at a population of 4.8 million. So began our family’s entanglement with this inscrutable, irresistible, impossible country.

My grandfather, George, had a job with a chemical company and a desire to live abroad. He had already done some traveling in Mexico, including a bicycle trip with friends when he was in his teens. When he and Beverly first arrived in “the D.F.”, they had plans to stay just a few years and then continue their expatriate adventures in other countries. But they fell in love with Mexico, and stayed twenty-five years, returning to the USA shortly before the catastrophic earthquake of 1985. They’ve always “lived a charmed life” as my grandmother (Lita) would say.

It was so easy to fall under this country’s spell and the life it offered an American corporate executive and his family. As Lita has repeated so many times, with a sigh of longing for the irretrievable past…it was a paradise. A paradise of gentle weather, friendly people, low costs and dutiful help. Of course, it wasn’t a golden age in every aspect. At least it wasn’t for many Mexicans, who grappled with the Tlatelolco massacre, poverty, inequality and the PRI’s “perfect dictatorship”.

My mom grew up as a chilanga, a skinny redhead cruising the streets of the messy behemoth built over the ancient ruins of Tenochtitilán in her yellow VW bug, bopping along to American pop hits on Radio Éxitos. She went north for college and then started her family. My parents educated the four of us at home, though “home” meant many places as we were growing up. I first visited Mexico City when I was nine; when I was fourteen, we made our first eight-month sojourn to San Miguel de Allende. Now I have two Mexican-born daughters. At this point, I can’t tell where the expatriate ends, and the immigrant begins.

In the long history of foreigners in this land, weaving a tapestry of both wonder and sorrow, one can always follow a particular golden thread: the desire to believe in Utopia, and that it can be found here. Cortés’s vision was of a gilded paradise, the Spanish friars saw multitudes of souls awaiting salvation and 19th century Americans and Europeans saw a bounty of untapped resources. Today’s extranjeros may see a place where they can shed the trappings of whatever society they called home and start fresh. They don’t want to acknowledge, much less explore, the darker side of this bewitching Neverland; perhaps they fear the spell will be broken and they will lose the lifestyle they have found here. But it might not hurt to be reminded of the people they passed on the way in, the ones going in the other direction on the conveyor belt. The immigrants.

We expats can escape from paradise if dreams turn to nightmares. How fortunate we are—able to leave behind the failed Utopias and run home to safety, knowing that they will let us back in.

Beautifully written and a very thought inspiring essay.

It made me reflect on my own experience on being an immigrant or considered an expat: Both in Switzerland where I immigrated to in 1973 as a 12-year old and suffered a culture shock - it was here that I first personally experienced what it means to be a foreigner in language, behaviour and perception, but I survived, indeed eventually thrived.

Then 18 years later, I met my „media naranja” a Chilanga, who was vacationing in Switzerland and who introduced me to Mexico and Mexican culture, opening up a whole new world of experience of what it means to be foreign and privileged as an expat.

With my new Mexican in-laws, as an Anglo-Swiss gringo, I experienced their generosity and curiosity and tested their patience and sense of humour. The result has been 30 years of happy marriage and two young adults adept at crossing the cultural divide between Switzerland, England and Mexico. This as well as a deep love and sometimes vexation with Mexico, a beautiful, complex and bewitching country.

Thus my background and motivation for subscribing both to MND and the Mexpatriate - and to keep up-to-date on Mexican daily life, society, history, culture and politics.

Dear Kathleen, I wish you and the MND team all the best and much success on taking over the reigns and look forward to your future coverage and comments on all aspects of Mexico and Mexican society.

Simon Kernahan

If you are interested in chatting, please contact me. Im starting my substack adventure and hopefully you remember myname