La Semana: Tuesday, Nov 8

The week in setbacks for the 4T's educational policy

Welcome to a Tuesday edition of The Mexpatriate.

In tonight’s newsletter:

The state of education in Mexico part II: la nueva escuela mexicana

If you read the Oct. 25 edition of Entre Semana, you got a preview of the magnitude of corruption and systemic institutional problems that have failed Mexican students for decades.

While Elba Esther Gordillo is just one woman, her case demonstrates how attempts at reform have been dragged through the mud of power politics time and again.

Tonight, I take a closer look at this administration’s efforts to cement an educational legacy.

The state of education in Mexico part II: la nueva escuela mexicana

On Oct. 19, the Department of Public Education (SEP) temporarily suspended a pilot program to implement a new curriculum in 960 public schools. This followed rulings by federal judges in favor of lawsuits brought against the program.

The judges essentially accused the institution of using students as guinea pigs “to determine the pros and cons of the new educational model, without taking into account the negative repercussions this could have on these students’ rights to an education.”

The department has announced they will challenge the rulings.

As the SEP has changed hands (a new director was announced in August) and confronts (or attempts to dodge) an acute educational crisis in the wake of the pandemic, the decision to implement comprehensive curriculum changes seems misguided at best. However, from the hurried perspective of a president whose lofty ideological aspirations and mega-projects have been truncated by global events, there is no time to waste.

“It is the dream of all specialists in pedagogy from the left…imagining a different kind of education, where the student is not a product, where everything isn’t made into a business…but rather is community-based,” said director of educational materials, Marx Arriaga, in a recent interview. When the outline of the program was announced in May of this year, Arriaga described the many sins the curriculum sought to remedy —classism, racism, misogyny—but provided few details about how exactly this would be achieved.

Some critics were appalled by what they viewed as a curriculum focused on “indoctrination” more than education. The impetus behind the self-described “nueva escuela mexicana” is to bring the crusade against neo-liberalism into the classroom, to shift the focus from “competencias” (competition or competence) to “compartencias”. This latter addition to the Spanish language (a play on the word “to share”) doesn’t appear to have the capitalists too frightened yet.

Following the failure to launch the program, Arriaga took his beleaguered textbooks on the road last week, initiating a “caravan” to promote the curriculum across the nation. Arriaga has claimed that Mexico would be the first country to try this alternative approach to public education in history; the goal being nothing less than to “decolonize” the minds of the next generation of Mexicans, liberating them from centuries of European structures of thought.

So what is different about this curriculum? Does it really set out to brainwash students into mini-AMLOs promoting the “cuarta transformación” as some fear? Or will it inspire a “revolution of consciousness” as claimed by Arriaga?

“The fundamental point of the connection between the content and the core concepts in a subject is achieved through instruction, which situates the points of articulation of the knowledge and understanding within teaching contexts (in which the teacher brings to bear his or her teaching knowledge) and learning situations applied to the daily life of the students.”

After 162 pages of this, I’m not sure how to answer the questions above, but the general takeaways are:

Community

Plurality

Inclusion

Human rights

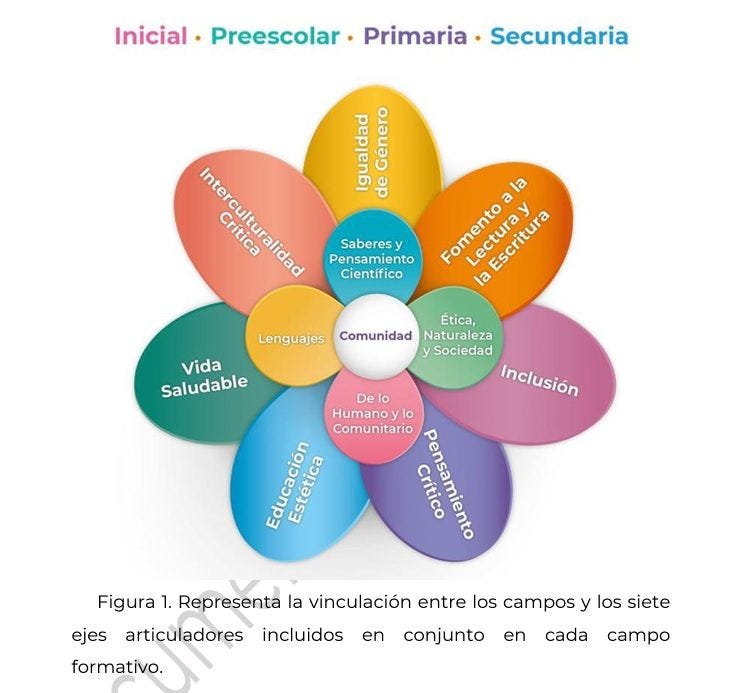

Grades are grouped together and labeled as “phases” and subjects are “educational fields”, which are supposed to be taught via a form of project-based learning.

“The intention is not to teach knowledge, values and attitudes so that children and adolescents can assimilate and adapt to the society they belong to, neither is the function of school to mold human capital from primary to higher education in response to the needs established by the labor market. Schools should create happy children and adolescents.”

Student and teacher evaluations are also modified in the plan, with a focus on “feedback”, “dialogue” and “self-reflection” rather than the “supposed quantification of knowledge that can be represented by numerical grades.” If the priority is happy students, I suppose it’s hard to argue with this approach.

The document also makes pointed reference to earlier attempts at educational reform: “…the rhetoric of quality as the basis for reducing the education of students and the work of teachers to instrumental criteria…opened the doors to the commercialization of primary education.”

The 2013 constitutional reform under President Peña Nieto looked to standardized testing, teacher evaluations and the weakening of the teacher’s union as mechanisms to improve outcomes on metrics that Mexico’s students had repeatedly failed. López Obrador reversed the reform in 2019.

As pundits and politicians argue about the ideological ramifications of this plan, it’s hard not to hear echoes of the recent debates playing out across schools in the US, which similarly reveal the tension between a proclaimed desire to create a more equitable society via textbook, and the messy reality of superimposing top-down change.

In Mexico, the focus has been on class more than race, and to a lesser extent, on gender. But in both countries, the diversity of schools across vastly heterogenous and unequal societies can create barriers to change that educators or policymakers may not anticipate. It turns out that families often prioritize the individual needs and aspirations of their children over the more abstract interests of society.

I feel I can approach this topic as a less excitable outsider, one who comprehends deeply the arguments for alternative education. I was home educated from first grade through high school, which is one of the reasons our family had the flexibility to travel back and forth to Mexico. My sisters and I enjoyed more freedom than our peers—days were not as routine, we could always visit museums or libraries during off hours—and we were the beneficiaries of a highly individualized education. My daughters attend a very small Waldorf-inspired private school, which at times strikes me as a cross between Hogwarts and Little House on the Prairie. And yes, I believe in protecting the fleeting magic, imagination and wonder of childhood, a gift I was granted during my own.

Is this gift a luxury, a privilege for those who can afford it? Or is it a brave middle finger in the face of conformity? Perhaps it is both.

Over the years I have come to understand better how much of my singular childhood was enabled by circumstance: I grew up in a one-income household, with my mother at home. I came from at least two generations of college graduates. My sisters and I were not at risk of being shut out from many opportunities, even if we learned algebra, literature and science at a different pace and in different ways than our peers. Instead of viewing public educational systems simply as tools of conformity and creatures of industrialism, I now see their profound value as a public good; a besieged but valiant effort to provide equal access to what has historically been off limits to most of humankind.

What we teach in schools has always been subject to ideological meddling, controversy and the zeitgeist of the era. In that classic defense of freedom of thought in education, “Inherit the Wind”, lawyer Henry Drummond observes of his opponent: “All motion is relative. Maybe it’s you who’ve moved away by standing still.” What we take for granted in today’s textbooks may have been considered uncouth, heretical or dangerous only a few generations ago.

This reform by the AMLO administration is a logical extension of the philosophy driving the “4T”. In a sense, the structure of modern schooling is anathema to their vision of a just society and when critics call out the importance of public education as a tool for social mobility, they may respond “so what?” Isn’t that really a euphemism that keeps the capitalist illusion in place? The concept of social mobility is rooted in the notion that acquiring certain education and skills will help you level up in this game we play, allowing one to aspire beyond humble origins, to detach from the moorings of class and “be free”.

Is this how it usually plays out in reality? It would be hard to answer “yes” in modern Mexico.

Here are a few sobering statistics from a 2019 study on social mobility:

74 of 100 Mexicans from the poorest segment of society will never break out of poverty in their lifetimes.

Only 5% of children whose parents who didn’t attend school will obtain a college degree; and just 13% will complete high school.

Meanwhile, a representative from UNICEF recently put the educational regression in Mexico in stark terms: a 2021 assessment of 1600 students (8-11 years old) revealed that 66% had not achieved basic reading skills, and 97% lacked basic math skills. “We are talking about educational consequences that will turn into income and quality of life consequences…a generation of students may never recover the years of learning lost.”

The promises of social mobility may be broken for many, but are the promises of new textbooks and new terminology any more likely to endure?