Stranger than fiction

A high-profile acquittal almost 20 years in the making

Welcome to The Mexpatriate.

President Claudia Sheinbaum ended last week on good news—following a call with Trump on Thursday, Mexico got another 90 days at its current tariff rate (25% on non-USMCA compliant goods) before the Aug.1 deadline for “reciprocal tariffs” to take effect on U.S. imports from over 60 countries.

Considering the administration’s brawl with Brazil and tensions with Canada, Mexico again comes out looking like the “special relationship” in the hemisphere. “More and more, we are getting to know and understand each other,” wrote Trump of his chat with Sheinbaum, who posted on X that the next 90 days will be used to “build a long-term agreement based on dialogue.” She also told reporters in her mañanera on Friday that a broad bilateral security agreement is on the verge of being reached.

In today’s letter, I cover the acquittal of Israel Vallarta—a major story that broke on Friday—but before I dive in, I have a few newsletter updates. This week I’ll be publishing Monday through Friday, covering one news story each day. I’ll include a reader survey in my Friday edition (please take a minute to respond), but in the meantime, feel free to email me at hola@themexpatriate.com with your feedback.

“A symbol of prolonged injustice”

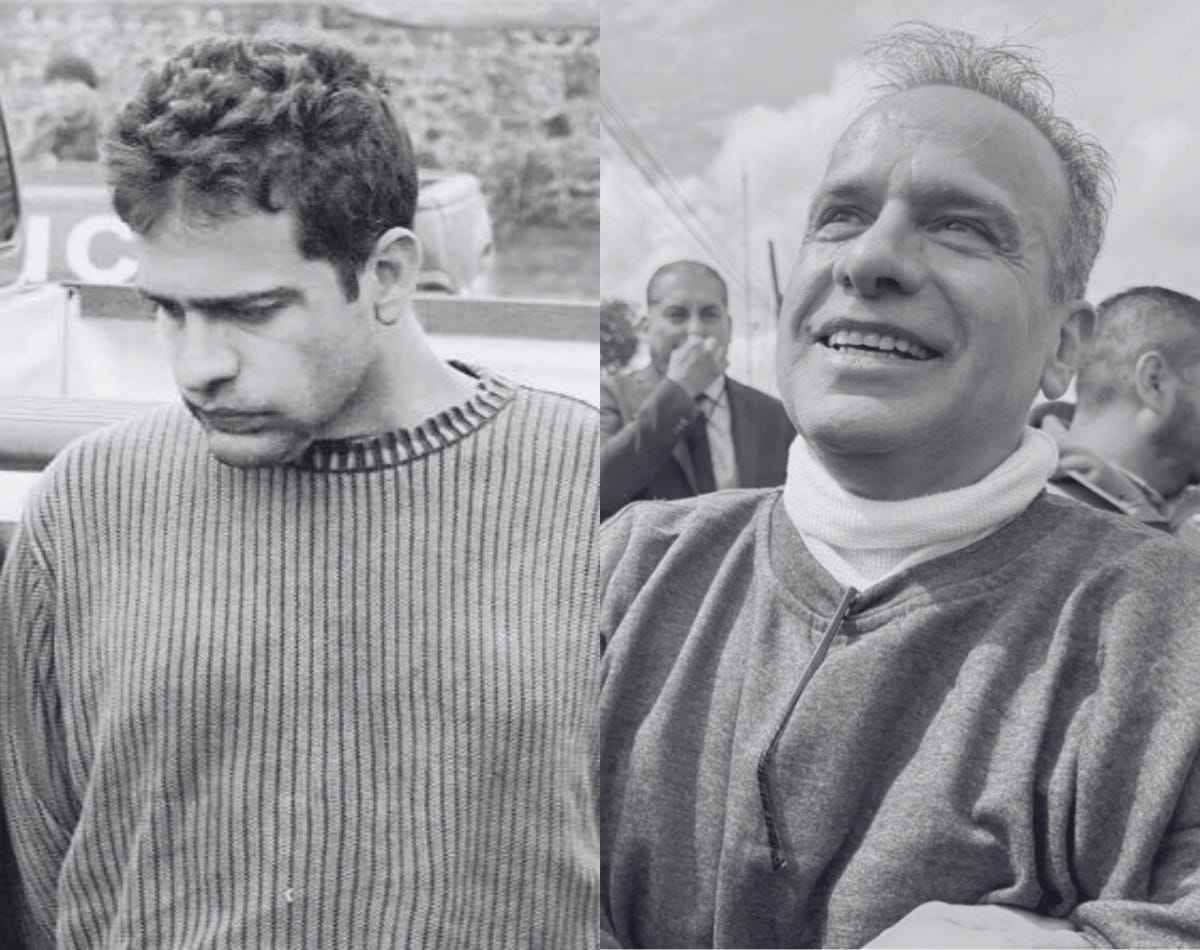

On the morning of Aug. 1, Israel Vallarta walked out of the maximum security El Altiplano prison in México state where he had been held for over 19 years. “I’m still in shock,” he said in brief comments to reporters, surrounded by his family. “I knew the truth would prevail, sooner or later.”

Mexico’s “most famous prisoner” had never been convicted or sentenced.

Vallarta is one of thousands unjustly imprisoned in Mexico—for example, Juana Hilda González, whose sentence was vacated in the Caso Wallace in June—but his high-profile story is a particularly emblematic one. As described in a statement published by the Federal Institute of Public Defenders (IFDP), Vallarta’s case is “a symbol of prolonged injustice.”

Vallarta was pulled over by federal agents on Dec. 8, 2005 on the México-Cuernavaca highway along with his French ex-girlfriend, Florence Cassez. Vallarta was tortured before being taken with Cassez to the ranch where he lived, and where the Federal Investigation Agency (AFI) told the media to show up early on the morning of Dec. 9. Video of the staged operation showed agents breaking down a door, rescuing victims and taking Vallarta (visibly bruised) and Cassez into custody—and was broadcast to a public hungry for justice during an epidemic of kidnappings.

The head of the AFI, Genaro García Luna (now serving a 38-year sentence in the U.S. for conspiring with drug traffickers), was caught in the lies on national television during an interview with journalist Denise Maerker. He claimed reporters had asked the agents to demonstrate how the operation was carried out, admitting that it wasn’t real-time footage of the arrest. Cassez called into the show from prison to confirm that she and Vallarta had been detained a full day before the press arrived at the ranch.

Vallarta and Cassez were accused of running a (likely mythical) kidnapping ring called Los Zodiacos, but their cases soon diverged. Cassez was tried and sentenced to 60 years, but under pressure from France that threatened to become a diplomatic incident, was released after her sentence was vacated by the Supreme Court (SCJN) in 2013. The story of Cassez’s victory (which the Mexican public had mixed feelings about) was always darkened by the shadow of Vallarta; the Mexican half of the case, left languishing in prison.

On July 31, a federal judge in México state issued an acquittal of Vallarta and ordered his immediate release. The federal attorney general’s office (FGR)—which earlier this year continued to seek a 329-year sentence for Vallarta on kidnapping charges—has five days to appeal the ruling. In 2022, AMLO had said “if it were only in my hands” he would pardon Vallarta, but that it wasn’t possible since he had never been sentenced.

Judge Mariana Vieyra Valdes had been reviewing the case since January, and there was concern that the judicial elections would throw yet another wrench into Vallarta’s endless legal nightmare if she was replaced by a newly elected judge in September (Vieyra won and will retain her judgeship). In her ruling, Vieyra drew on the SCJN decision to release Cassez, based on the “corrupting effect” of police misconduct in the arrests and in the prosecution of the case (including repeated use of torture), concluding that “with this evidence, it is impossible to establish the guilt of the accused.”

Belgian journalist Emmanuelle Steels, who wrote a book about the case (“El Teatro del Engaño”) in 2015, said in an interview with Proceso that this is a bittersweet moment:

“This is a great victory; what matters most is that this man is free and recognized as innocent. But on the other hand, here’s a man who spent nearly 20 years in pre-trial detention, who served a sentence that never existed, and this will remain a huge stain on the judicial, media and political history of Mexico.”

Vallarta’s wife, Mary Sainz (they married in 2017), has been a tireless advocate for his release and has asked that President Sheinbaum make a public apology to her husband. “It isn’t about revenge, but there should be justice.” Sheinbaum said on Friday that Vallarta is entitled to seek reparations from the state.

Vallarta has said he plans to focus on his family, but also that he will seek justice against those who put him in prison.

“There will be consequences…more truths will come to light.”

Going deeper: If you want to learn more about this case, check out the 2022 Netflix documentary “El caso Cassez-Vallarta: Una novela criminal.”

If you want to support my work, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. I’ll be back in your inbox tomorrow!

But what is the bigger picture? Why were this couple arrested? Was it just a bureaucratic mistake? Was it the result of a personal grudge? Or does it have some political dimension?