Is free speech under threat in Mexico?

Questions about censorship in the national conversation, plus what I'm reading

Welcome to The Mexpatriate.

In today’s newsletter, I dive into the recent national conversation on censorship, from banning narco corridos to foreign propaganda (in the shape of “ICE Barbie” Kristi Noem in a lavender blazer), and also share links to what I’m reading.

Curious about what’s happening with the judicial election campaign that launched a month ago? Stay tuned for my next newsletter for paid subscribers—and if you haven’t yet, please upgrade below. Thank you for supporting my work!

Defining the boundaries on freedom of expression has been a simmering topic in Mexico this month.

First, there was the face of Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG) leader “El Mencho” staring at the audience from a giant screen in an auditorium near Guadalajara, the backdrop for a song about the cartel boss performed by the Sinaloan band Los Alegres del Barranco. The concert was held just a few weeks after the horrors of the CJNG-operated camp at Izaguirre Ranch in Teuchitlán, Jalisco had gripped national headlines.

On April 1, the U.S. State Department canceled visas for the group to perform a 10-concert tour. “The last thing we need is a welcome mat for people who extol criminals and terrorists,” wrote Deputy Secretary of State Christopher Landau in a post about the visa revocation on X.

The CJNG was designated by the U.S. as a foreign terrorist organization (FTO) along with five other Mexican cartels in February and reportedly, the Trump administration is contemplating restrictions on other performers. As noted by journalist Ioan Grillo in a recent report:

“On March 27, a jury found José Ángel Del Villar, CEO of L.A.-based Del Records, guilty of violating the Kingpin Act; he was convicted of working with a Mexican partner who laundered money for the Jalisco Cartel. Del Villar faces up to 30 years in prison in his August hearing. The terrorism designation of cartels makes cases like this easier for prosecutors and the punishments worse.”

This move by the U.S. has also “given momentum to the prohibitionist side” in the ongoing Mexican debate about narco corridos.

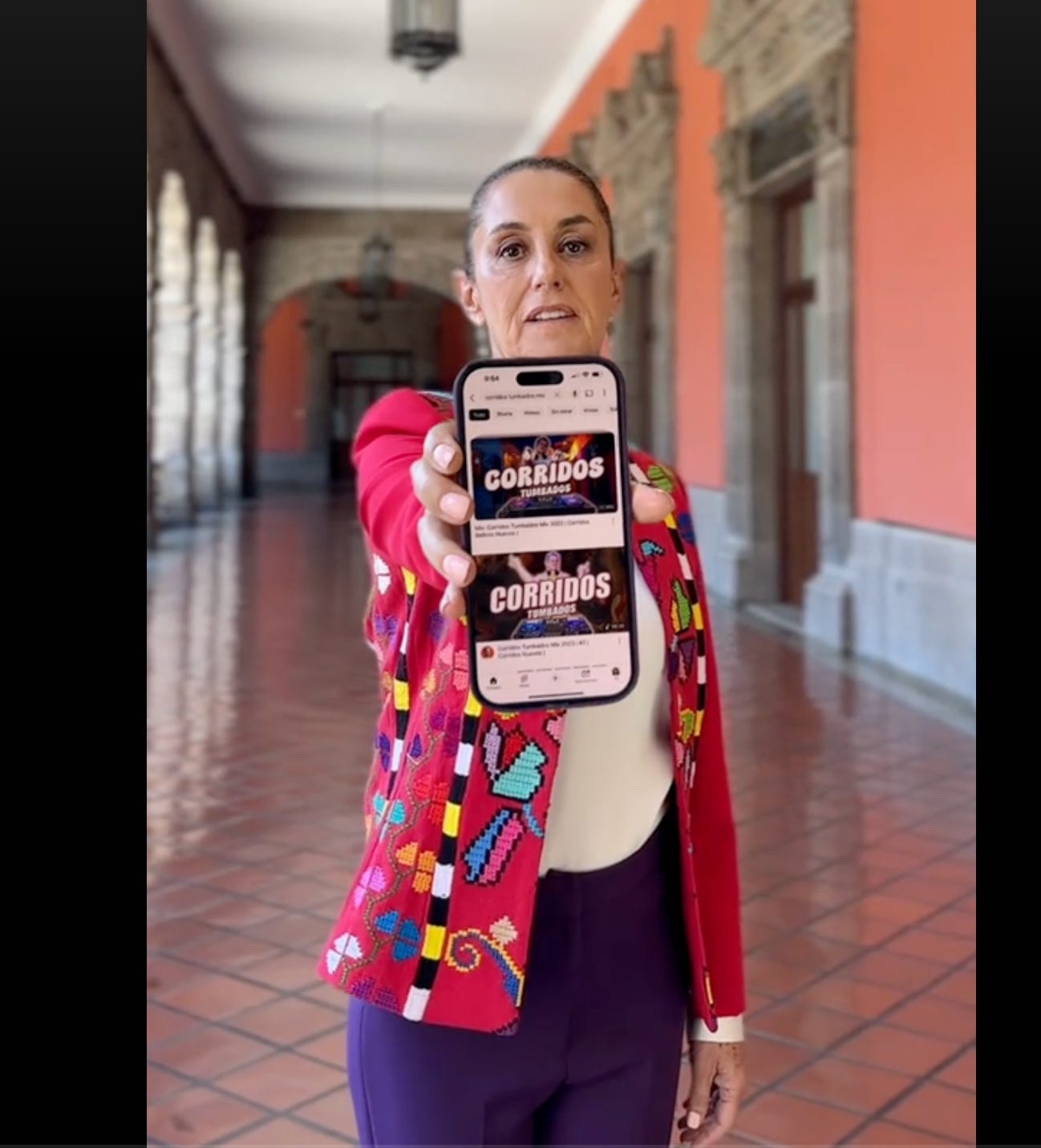

A Morena federal deputy presented a bill on April 8 to modify the penal code to broaden the definition of “apología del delito,” or defense of crime, which could include narco ballads. Nayarit, Michoacán and Aguascalientes have recently instituted statewide bans on performance of narco corridos, while President Sheinbaum has resisted the idea, instead announcing the “México Canta” competition to encourage artists to gradually leave lyrics about drugs and violence behind.

“We are not banning a musical genre,” she said. “That would be absurd.”

Meanwhile, in keeping with the inevitable blowback of prohibition (the more you try to hide something, the more people want to look at it), the song in question, “El del palenque,” skyrocketed to number one on Billboard’s LyricFind Global chart, which ranks the “fastest-momentum gaining tracks in lyric-search queries and usages.”

Musicians find themselves in a delicate position: face possible legal action for glorifying violence, or face the wrath of their fans. A concert by Sonoran singer Luis R. Conriquez at a Texcoco festival devolved into chaos on April 11 after he told the audience he wouldn’t be singing some of his trademark “corridos bélicos.” The furious (and likely intoxicated) crowd trashed the stage.

“I didn’t get angry,” Conriquez said in an interview with Ciro Gómez Leyva. “In some ways, I understand them…but I’d been singing for an hour and a half and they wanted the more explicit corridos…unfortunately, they like the more explicit ones.”

But broader public opinion may be moving in the other direction. An Enkoll phone poll in México state after the Texcoco incident found that 63% of respondents were in favor of banning the performance of “narco corridos or music that incites violence” in live concerts at festivals or other public events (with the strongest support from those ages 55-64).

However, it wasn’t controversial song lyrics that halted Morena’s telecommunications reform in its tracks last week, and put Sheinbaum on the spot.

When an anti-immigrant ad starring U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem aired during a primetime Liga México soccer game on Mexican television, the widespread outcry spurred Sheinbaum to respond. In the clip, Noem threatens the U.S. government will “hunt down” undocumented migrants as Trump “Makes America Safe Again.”

The ads had actually been airing in Mexico for weeks, part of a multimillion-dollar Trump administration campaign, but didn’t receive national attention until the América-Mazatlán match. Sheinbaum called out the campaign as “discriminatory” and requested Mexican networks pull the ads.

Was it legal for the U.S. government to purchase airtime on Mexican television?

According to some interpretations of the law on discriminatory content, the answer is no. But the regulatory entity in charge of broadcasting since 2014, the Federal Telecommunications Institute (IFT), was one of the independent bodies dissolved in a Morena constitutional reform in November—its functions have yet to be transferred to the new Digital Transformation and Telecommunications Agency (ATDT).

Sheinbaum asserted that Peña Nieto’s 2014 telecoms reform removed a clause preventing foreign political propaganda from airing in Mexico (some analysts have argued otherwise), and promised to plug this legal loophole in the Morena telecommunications bill already under discussion in Congress. “We believe that our sovereignty and respect for Mexico warrant reinstating it into the law.”

As has been the case with most reforms since Sheinbaum took office, the updated legislation was supposed to pass rapidly through the congressional assembly line (certainly too quickly for most lawmakers to read it).

But someone did read Article 109 of the bill, and it raised red flags:

“The competent authorities may request the collaboration of the agency (ATDT) to temporarily block a digital platform, in cases where it is appropriate due to non-compliance with provisions or obligations established in the respective regulations applicable to them.”

The vague language led opposition politicians to accuse Morena of trying to sneak in a “Censorship Law” that would allow the government to shut down digital platforms for indefinite reasons and periods of time. As The Mexico Political Economist put it: “In a country where the government tends to control the day to day political agenda, for once, Mexico’s weak opposition made itself heard.”

The backlash led Sheinbaum to call for a timeout. As of today, the bill has been returned to congressional committees for a “comprehensive review,” according to Morena’s vice coordinator in the Senate, Ignacio Mier.

“That article was just added, but the law had been worked on for some time,” Sheinbaum said on April 25. “It doesn’t have anything to do with censorship of content…but regardless, that article needs to be clarified…Mexico’s government will absolutely never censor anyone.”

As in much of the world, upholding the principle of freedom of expression is easier in theory than in practice in Mexico. We may (mis)quote Voltaire about disagreeing with what you say, but defending to the death your right to say it—until the pendulum swings, and find the other side goes too far, the offense is too outrageous, the potential harm too great.

And governments will always be tempted to scapegoat someone who says the wrong thing, rather than try to right the wrong.

What I’m reading

Deception in paradise (Bloomberg)

This investigative report on victims of real estate fraud in Tulum comes as the tourist haven also faces increased security issues (the city’s security chief was shot and killed in March). If you want to go further, check out an interview with the reporter who wrote this story, Andrea Navarro, on MexMoves podcast.

If you want to read something uplifting about U.S.-Mexico relations for a change, you’ll enjoy this overview of how INAH and the U.S. Embassy in Mexico have worked together to recuperate Mexican artifacts (11,000 pieces over nine years).

The Endangered Rio Grande Can Still Be Saved: A podcast with Maria-Elena Giner (The Border Chronicle)

This interview with the former International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC) U.S. commissioner (who was asked to resign last week by the Trump administration) gives a thoughtful, expert perspective on the water challenges faced on both sides of the border. “Change comes at the rate of trust,” says Giner, whose tenure saw binational conflicts not just over the Rio Grande/Bravo but also over San Diego-Tijuana sewage treatment.

Los jugadores de la NFL que quieren tener equipos en México (Whitepaper)

In February, retired NFL player Ryan Kalil and a group of other athletes bought the Monterrey Fundidores, a team in Mexico’s Professional American Football League (LFA). In this piece, Kalil talks about his reasons for investing in a Mexican team (renamed the Monterrey Osos), and his plans to help elevate the league—including with a documentary, following in the footsteps of Ryan Reynolds and the Netflix hit “Welcome to Wrexham.”

The Weirding of the Drug Supply (Dreamland: A Sam Quinones newsletter)

“There are no studies of the effects of BTMPS on humans – why would there be? No one ever imagined a human consuming it.”

Sam Quinones, journalist and author of an excellent book about the U.S. opiate epidemic (“Dreamland”), writes about an industrial UV stabilizer that is increasingly being found in fentanyl in U.S. cities. It’s unknown why this particular chemical is showing up in the street drug supply, but serves as yet another example of how, as Quinones puts it, “the era of ‘risk-free’ recreational drug use is emphatically over.”

Thank you for reading and feel free to send me your suggestions, comments and questions at hola@themexpatriate.com. And please share The Mexpatriate with other Mexico-philes!