La Quincena: Tuesday, Jan 31

2023 is off to a wild start

Welcome to the first 2023 edition of The Mexpatriate.

To say Mexico’s first month of the year has been eventful is an understatement.

The first headlines included a bloody Jan. 1 raid on a prison in Ciudad Juárez which resulted in the escape of a notorious gang leader (“El Neto”) and 29 other prisoners; the election of the first female chief justice of the Supreme Court; the re-capture of the son of “El Chapo” and ensuing violence in Sinaloa; the death of fugitive “El Neto” in a confrontation with law enforcement…and this was just before the kids went back to school.

The next week brought the North American Leaders’ Summit, 11 arrests in connection with the attempted murder of journalist Ciro Gómez Leyva and the official announcement from the “Va por México” coalition that they will anoint a single candidate in the 2024 presidential election. The Mexico City Metro subway system suffered multiple accidents (which authorities appear to blame on sabotage), and on Jan. 17, the long-awaited trial of Mexico’s former security chief, Genaro García Luna, began in New York.

Where to begin?

In tonight’s edition, I tackle:

Breaking the curse of the “Culicanazo”? The capture of Ovidio Guzmán

Negative space: the invisible issues at the North American Leaders’ Summit

You can expect to receive “La Quincena” every two weeks in your inbox. Thank you for subscribing!

Breaking the curse of the “Culicanazo”? The capture of Ovidio Guzmán

“The names on the rap sheets would change, but the shape would stay the same. In fact—give or take some minor changes—the same hierarchy of producers, intermediaries, and wholesalers still structures the Golden Triangle’s drug trade today.”

—The Dope: The Real History of the Mexican Drug Trade by Benjamin T. Smith

In the early hours of Thursday, Jan. 5, it was clear something was afoot in Culiacán, a city of over 800,000 residents and capital of Sinaloa. First came reports of “narcobloqueos” and shootouts, and instructions by local officials to stay at home. School was cancelled and government offices closed. By around 9 a.m., news outlets started reporting that Ovidio “El Ratón” Guzmán, son of Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzmán, had been captured. Guzmán had been flown in the wee hours of the morning to a military base in Mexico City, and then transferred to the same maximum security prison his father had tunneled his way out of in 2015.

The security operation was touted as a success by the government, and by most observers (even political opponents), though it was also a costly one. The official toll is 29 dead (10 of them military) and 35 wounded, however, residents of the town (Jesús María) where Guzmán was detained have since claimed that over 100 people have disappeared. Hundreds of cars were stolen, many of them set on fire, and businesses were ransacked. Shooting at the Culiacán airport grounded flights after a bullet pierced the fuselage of an Aeroméxico plane. The Mazatlán airport also temporarily shut down for security reasons.

This operation, coming a matter of days before Air Force One touched down in Mexico City for the North American Leaders’ Summit, has been viewed as an offering for President Biden, but it also holds potent symbolic significance for President López Obrador.

Security analysts and journalists who follow organized crime seem to agree that “El Ratón”—while wanted by the U.S.—was not the most powerful of cartel leaders: the 32 year-old was one of “Los Chapitos”, as El Chapo’s sons’ gang (part of the Sinaloa Cartel) is known, but wasn’t at the top.

“El Ratón” and his brothers are known as methamphetamine and fentanyl traffickers, but they also dominate the local drug market with marijuana dispensaries modeled on what you might find in California or Colorado, though selling cannabis remains illegal: “Mexico’s Senate is taking forever in approving a bill to legalize cannabis, but in Culiacán they have gone ahead and effectively legalized it themselves,” notes journalist Ioan Grillo.

However, Guzmán’s previous capture on another Thursday in October 2019 has lingered as a black mark on AMLO’s term. On that day, the explosion of violence in the city of Culiacán in response to Guzmán’s detention was so intense that the president ordered his release to “prevent further bloodshed.” Even within the context of AMLO’s strategy of “hugs not bullets”, this was a humiliating law enforcement failure.

Perhaps it also signaled a turning point in the administration’s security policy: since that “Black Thursday”, there have been several high-profile captures including Rafael Caro Quintero (July 2022) and the brother of “El Mencho” (December 2022), which belie the president’s earlier assessment that capturing capos was a futile strategy that only generated more violence. Of course, ensnaring crime bosses does generate something else: media attention. As the 2024 presidential electoral showdown nears, that might be exactly what AMLO and his party need.

Guzmán has been granted a hold on extradition to the U.S., where he would face charges of conspiring to distribute cocaine, methamphetamine and marijuana. The U.S. government has until Mar. 5 to present a formal request for extradition, which according to an arriagnment judge at the Altiplano prison, the U.S. State Department has yet to submit.

Meanwhile, the head of public security, Rosa Icela Rodríguez, has announced the Mexican charges against Guzmán include weapons possession, organized crime and homicide, all crimes committed in flagrante during his capture. In fact, the warrant for Guzmán’s arrest had not been updated since 2019, an indication of the country’s criminal justice approach with kingpins—it isn’t about building a solid case, but rather using military tactics to trap high-profile targets wanted by the U.S. and outsourcing their prosecution.

As Guzmán awaits his fate, it’s hard to say what impact his detention will have on the Sinaloa cartel or its business. AMLO’s own arguments against the nabbing of capos could be validated if there is an uptick in violence caused by destabilizing the power dynamics between rival factions. “If in the coming months, there is a new split in the Sinaloa cartel or the CJNG (Jalisco New Generation Cartel), we will have a third cycle of violence, just as tragic and destructive as the prior two,” notes security analyst Eduardo Guerrero, referring to the first conflict between the Sinaloa and Beltrán Leyva cartels during the Calderón administration, and the second wave of violence instigated by the rise of the CJNG in the Peña Nieto sexenio.

Nationwide, homicide figures for 2022 showed a 7.1% decrease compared to 2021, and Sinaloa has been one of the administration’s favorite examples of a declining murder rate—days before the capture of Guzmán, it was reported to be at its lowest level in 30 years.

In the broader history of “The Golden Triangle”—which as early as 1947 was responsible for producing around 90% of illegal drugs for the U.S. market—this dramatic event seems unlikely to bring profound change.

Negative space: the invisible issues at the North American Leaders’ Summit

Part I

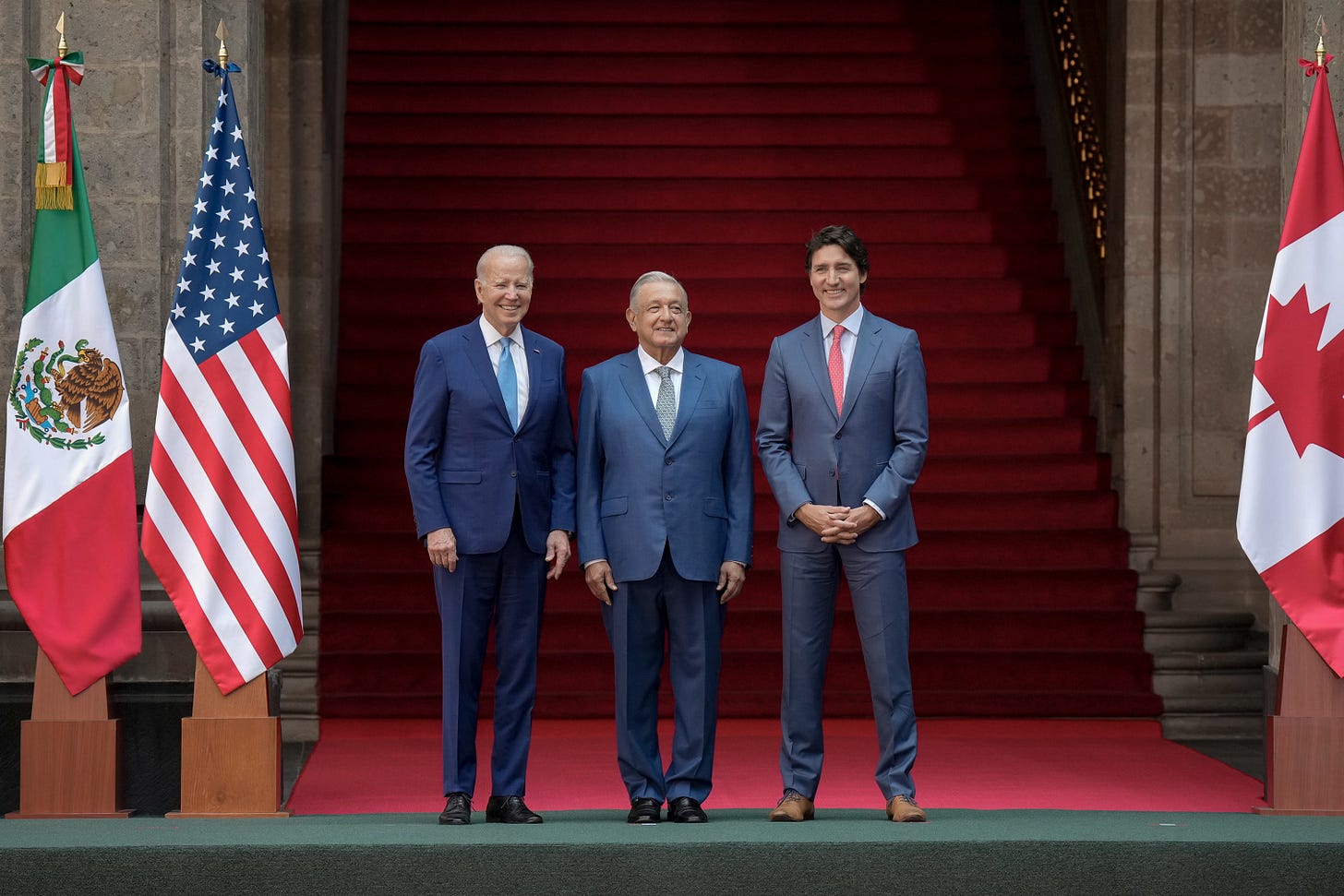

The Declaration of North America (DNA) that came out of the “Three Amigos” summit held in Mexico City from Jan. 9-10 reads kind of like my new year’s resolutions from years past—sweeping in ambition, short on details and accountability.

“Address the root causes and impacts of irregular migration and forced displacement” and “support countries across the Western Hemisphere to create conditions to improve quality of life” seem not too-distant cousins of “learn Arabic” or “run a marathon”.

This is not surprising of course. Global diplomatic events are practically designed for this kind of output: an opportunity for public posturing, awkward embraces, shoe-staring (as demonstrated by Biden and Trudeau during AMLO’s 28-minute response to a reporter’s question), and for observers, reading the negative space. By this, I mean the items that were absent from the agenda, but which indubitably shape the contours of the trilateral relationship.

The most explicitly verboten topic was the ongoing energy dispute between the U.S. and Canada vs Mexico. While the complaint lodged under the USMCA still hasn’t proceeded to the escalation of a dispute panel, the two sides seem at an impasse. Mexico’s Secretary of Economy, Raquel Buenrostro, said in a December meeting with U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai that Mexico seeks to “reconcile differences…without the need of reaching an arbitration panel and while guaranteeing national sovereignty.”

Meanwhile, some private investment projects by U.S. and other foreign companies (including in wind and solar energy) remain stalled by lack of permits, while other joint projects with state-owned Pemex and CFE move ahead. AMLO’s commitment to prioritizing the national companies has not wavered, even as both show staunch lack of progress in improving efficient use of resources: Pemex recorded a net loss of US $2.7 billion in Q3 of 2022, while other global oil companies raked in profits. The CFE looks healthy by comparison, but also saw increased losses in the 2019-22 period as the restrictions on access to cheaper sources of energy (generated by private plants) have raised costs.

While AMLO has been vocal about defending Mexico’s sovereignty in the face of rapacious foreign companies—enabled by his predecessor’s “neoliberal” policies—he also happily announced last week his successful meeting with representatives of four Canadian companies who had expressed concerns about his administration’s energy policies, as well as alleged extortion faced by some mining operations in Guerrero.

“…We resolved the problems without any obstacle,” said the president.

As the three leaders touted their efforts to increase and expand regional economic integration—much of it framed in the context of moving away from Asian supply chains—it’s hard not to see how the border-transcending shadow economy also wields influence: the black markets in drugs, weapons and people.

To be continued…