"Mexico should lead this conversation"

Former senator Alejandra Lagunes talks about the "psychedelic renaissance" and Mexico

Welcome to The Mexpatriate.

Alejandra Lagunes served as a federal senator from 2018-24 (representing the PVEM, or Partido Verde Ecologista de México) and made headlines in 2023, when she introduced a bill to decriminalize psilocybin and psychedelic mushrooms in Mexico.

Last month, I met with Lagunes at her well-appointed apartment in Polanco (guarded by a posse of ferociously fluffy Pomeranians) to talk about the legislation and the current outlook for psychedelic science in Mexico.

Lagunes has a background in tech (not uncommon among acolytes of the psychedelic revival). She worked for Google México, ran digital strategy for Enrique Peña Nieto’s administration and AI regulation is another area of interest—she is a founding member of the National Alliance for Artificial Intelligence (ANIA).

The bill Lagunes introduced has stalled, but it could be its time is coming, as the global research, development—and commercialization—of psychedelic medicines is at a crossroads. Last year saw a setback when MDMA failed to get its anticipated FDA approval for treatment of PTSD, but the newly appointed U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., has come out publicly in favor of researching substances like psilocybin and ibogaine (during his presidential campaign, he said he would “deschedule” psychedelic medicines). On April 7, New Mexico became the third state (following Oregon and Colorado) to establish a medical psilocybin program.

As you’ll learn below, there are legal gray areas for psychedelic compounds in Mexico (for example, ibogaine is unregulated, though it’s on Schedule I in the U.S.), but most remain illegal except for use by indigenous communities.

Can Mexico be part of the future—not just the history—of psychedelics?

NOTE: This interview was conducted in Spanish. It has been translated into English and edited for length and clarity.

How do you see the “psychedelic renaissance” today and Mexico’s place in it?

This is a response to the global mental health crisis we’re experiencing. Since the pandemic, there has been a considerable increase in cases of depression, anxiety, substance abuse and addiction.

We only have four psychiatrists for every 100,000 inhabitants in Mexico and a medical system that can’t provide either support or solutions to this crisis.

Many people who take antidepressants or similar medications are developing resistance, and are seeking alternatives. With modern medicine falling short, innovation is emerging through these molecules, through psychedelic medicine, which is actually ancestral medicine. Major research institutions are conducting clinical trials, and some countries are already regulating and making progress in this area.

However, this “psychedelic renaissance” also carries big risks, some of it coming from the New Age movement, which can lead to misuse of these substances. This can lead to adverse reactions, and it could jeopardize all the scientific progress we've made on the benefits of these molecules in treating depression, anxiety, trauma, and addictions.

“We’re at a moment that demands a lot of responsibility.”

We already saw a bit of this with what happened with the FDA and MDMA in the United States. And we’re also seeing it in Mexico, with bad practices by pseudo-shamans and fake healers who administer these medicines without proper preparation, and people end up in a worse place than where they started.

We’re at a moment that demands a lot of responsibility. I really like Jamie Wheal and his work—he has spoken about the enormous responsibility involved in how we use, regulate, and share these medicines as super powerful, ancestral technologies.

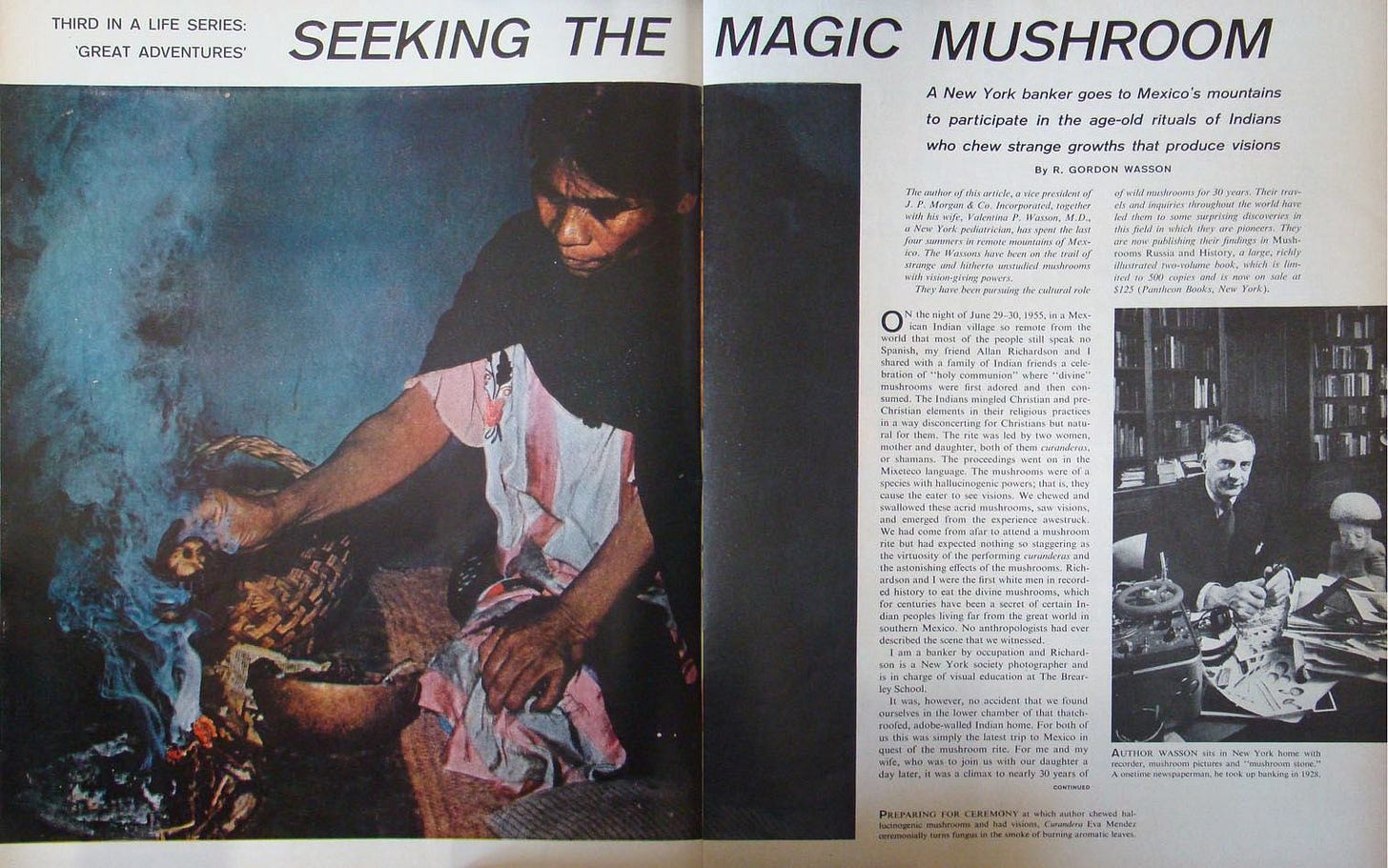

Wheal was actually here for an event in November and he said it felt like coming home, because Mexico is the epicenter. It was from here, through María Sabina, that knowledge of “magic mushrooms” spread. But we don't just have mushrooms here—we also have peyote, the Sonoran desert toad (bufo alvarius), and many other psychoactive plants too. And we have the indigenous cultures who have been using them for millennia as part of their medicines and ceremonies.

The question is: How do we regulate this? How do we integrate ancestral knowledge? How do we center the indigenous peoples who have been exploited for centuries?

You presented a bill in the Senate to decriminalize psilocybin and “magic mushrooms” in October 2023. Why did you decide to tackle this issue?

During the pandemic, in Valle de Bravo, I started researching what was happening globally. I also had gone through my own mental health crisis: panic attacks, anxiety. And I decided that when I return, I’m going to present an initiative to reclassify mushrooms and psilocybin.

Currently, they’re on Schedule I of the General Health Law—the most restrictive category—the same as substances like heroin or cocaine, considered highly harmful and without therapeutic value. How is it possible that these medicines are on Schedule I? Fentanyl is on Schedule II. Cannabis has already been reclassified. So, my intention at first was just to create a three-page initiative to reclassify and decriminalize psilocybin.

And at that moment, the universe started connecting me with key people, including representatives of indigenous groups like the Mazatec and Wixárika.

That’s when I realized this was much deeper than one initiative.

We began a collaborative process and wove together this proposal, centering indigenous peoples. Mexico has the richest psychoactive flora and pharmacopoeia in the world. But we also have living ancestral knowledge and communities that still use these medicines. We’re also a bridge to other indigenous groups in Latin America and the United States.

So I reframed my role as a senator: I understood that I had to be a bridge between the ancestral and the modern.

What is the scope of this bill?

The bill took months of work with psychiatrists, therapists, drug regulation experts, legislators, academics and indigenous people. For example, the Wixárika people asked us not to include peyote in the bill because it is endangered.

Another decision was to use the term “entheogen” instead of “psychedelic,” because of the stigma attached to the latter—entheogen means “God within.” We want this initiative to serve as the opening of a discussion, to be of the calibre that Mexico deserves, and that these medicines and the indigenous peoples deserve.

“Mexico should lead this conversation—from the perspective of ancestral medicine, not just from a focus on certain alkaloids. Yes, those are valuable, but for us, the conversation goes deeper: the mushroom is the medicine, in its entirety.”

We decided to start with mushrooms because they grow in many regions, there’s significant global progress already with psilocybin, and there are phase two and three clinical trials. It won’t be long before psilocybin capsules will be FDA-approved.

That’s why we proposed reclassifying psilocybin and psilocin (the mushroom alkaloids) from Schedule I to Schedule III, which would allow licensed doctors to prescribe them.

And regarding mushrooms themselves, we made an innovative decision: to give them their own chapter in the General Health Law, called “entheophytes.” This chapter covers ceremonial use, with mechanisms to include indigenous communities in resource distribution and ensure their participation, as well as protection of genetic heritage. There are mushrooms endemic to Mexico that can’t be patented, for example, those that grow only in the Mazatec region.

Although ceremonial use already has some legal protection, there are gray areas. There have been elders jailed for carrying their medicines. Currently, they can only share them within their territory, and with members of their own ethnic group.

We want this law to fully protect them—to let them use, share, and travel with their medicines without fear.

The bill also takes into account the different ways to administrate mushrooms. Our belief is that ceremonies should be led by indigenous peoples, not by a therapist. Why? Because they are rituals, specific elements are invoked, certain deities. Each elder does it differently, but always with ritual.

In a clinic, there are no such rituals. You put on headphones, they give you the molecule—but there’s no ceremony. That’s a session, not a ritual. A therapeutic session should be offered by trained health professionals prepared to work with these medicines. It’s not the same as giving someone an antidepressant. It requires different knowledge and support, different integration.

Specialists should be trained to offer psychedelics with authorization in safe clinics, because we need to ensure people’s integrity. As a patient, I want to know that the person administering it is prepared and the place is safe. What’s at the heart of this law is safety, integrity and people’s health. That’s why we are very clear: this is for therapeutic use.

We’re also working with UNESCO for this ancestral knowledge to be recognized as intangible cultural heritage of humanity. We want Mexico to ask the INCB (International Narcotics Control Board) and the United Nations to review the international drug lists.

“We want clinical trials in Mexico, with Mexican mushrooms, for Mexican patients.”

Mexico should lead this conversation—from the perspective of ancestral medicine, not just from a focus on certain alkaloids. Yes, those are valuable, but for us, the conversation goes deeper: the mushroom is the medicine, in its entirety. What makes the mushroom powerful is the combination of all its alkaloids. That’s the technology: a key to the subconscious.

Why does it work? It’s been scientifically shown that it generates neuroplasticity. The thought patterns that generate habits or addictions are interrupted. They act on dopamine, serotonin receptors—those chemicals that make us feel good…or bad.

But it’s not magic, and it’s not for everyone.

That neuroplasticity also makes you vulnerable, and exposed to potential abuse. That’s why our initiative is so strict. Because there have been victims of abuse, even at the hands of so-called shamans and therapists.

I want to send a clear message here: these substances are currently illegal, but there’s a massive black market of course—chocongos (psychedelic chocolates), ceremonies happening everywhere. We can’t be naïve. If they’re already everywhere, people need to be informed and prepared.

It’s a great opportunity, like a “reset” for your brain. But there’s work to do. From who you do it with, making sure it’s not mixed with other substances, where you do it—and most of all—how you integrate it afterward. What do you do with the information you received? How do you integrate it into your life?

The most important thing I’ve learned is that you reclaim your agency. No more gurus, the healer is you. These medicines give that responsibility back to you.

How can these treatments be made accessible to the wider population?

It’s really important to start with research. We want clinical trials in Mexico, with Mexican mushrooms, for Mexican patients. And if those studies show good results, then we can think about integrating it into the public health system, and making it accessible.

Today, in the U.S., a psilocybin session can cost up to US $5000. Is that healthcare?

It’s a “psychedelic renaissance” for the rich—the 1%. It shouldn’t be like that. In Mexico, we believe this should be for everyone, that it should be part of public healthcare, with fair costs, so everyone can access it.

What’s next for the bill?

It’s been sent to the Senate’s Health Committee and the Legislative Affairs Committee. We’re still pushing, not just with interested senators and representatives, but also with the government.

The National Commission on Mental Health and Addictions (Conasama) was created about a year and a half ago. They’re very interested, as is the National Psychiatry Institute (INPRFM). Doctors here want to research, but we need the health regulatory agency (Cofepris) to open the door.

But doing research is expensive. And since they’re illegal, access to the molecules is very limited. It’s a vicious cycle. That’s why we need the government to support this.

That’s the first big step. And from the Senate, this bill can serve as the foundation for debate. Of course, it’s not perfect. It can be improved. But the truth is, it’s urgent. In Mexico, suicides are rising alarmingly, especially among young people. Depression and anxiety are becoming normalized even among children, and they’re being medicated. That’s substance abuse too, even if it’s pharmaceutical. One pill to sleep, another to wake up, one to focus, another for energy, plus alcohol…We’re normalizing abuse. And that’s very serious. I see it across all ages and social classes.

This is a great opportunity for Mexico. We have the ancestral knowledge, the indigenous peoples who know how to do this, and we can build a bridge with modern medicine, psychiatry, technology. We could create a mental health system that’s innovative, yet ancestral and multicultural—one that combines the best of everything.

Do you think the change in administration in the U.S. could help make way for decriminalization here?

I’m very hopeful about what’s happening in the United States. If the new Secretary of Health starts to shift things, that will have a global impact. The U.S. has a lot of influence over these lists. Nixon started them in the 1970s, and everyone else had to follow.

Hopefully, the new administration will open up the conversation. So psychedelics will stop being a taboo, the research from the 1950s can start again. We don’t have to decriminalize right away—but we should at least reclassify. Take them out of Schedule I, to allow real research. It’s already happening, at Johns Hopkins, MAPS, even here in Mexico, the studies that have been done with ibogaine.

A lot of people today are just barely surviving—others are taking their own lives. This crisis is as serious as the climate crisis. And we have few practical solutions right now.

Honestly, I think the arrival of this administration—considering Kennedy’s vision of psychedelics—could be a game changer.

Thank you for reading and feel free to send me your comments and questions at hola@themexpatriate.com. If you enjoyed this interview, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription below for full access to The Mexpatriate.

Tx , K, for Clarifying parts of the article regarding some comments i raised

"Mexico should lead this conversation—from the perspective of ancestral medicine, not just from a focus on certain alkaloids. Yes, those are valuable, but for us, the conversation goes deeper: the mushroom is the medicine, in its entirety. What makes the mushroom powerful is the combination of all its alkaloids. That’s the technology: a key to the subconscious." What a giant step. Look forward to hearing how the legislation progresses.