The elephant in the room

Mexico in the time of the MAGAverse

Welcome to a news roundup edition of The Mexpatriate.

“Look at how the economy comes back in one day…this is what happens when you elect a businessman as president.”

“We need Donald Trump to get Latin America back on track.”

“He will hit Maduro hard…I say, have at him.”

“¡Amo el imperio!”

These are snippets of conversation from a lunch I went to two days after Trump’s victory. All of the comments I listed above were made by either Mexicans or Venezuelans. After 48 hours of soaking up my own algorithmic feed of laments and post-election stress disorder from the U.S. side, I was jolted by the lack of animosity towards Trump among people who might be expected to despise him. One Mexican-American from Chicago said she wasn’t a fan, but that all of her siblings (second-generation immigrants) are “trompistas.”

The story of the Latino vote in pushing Trump back into the White House will take time to unpack, but listening to that conversation felt like a timely reminder that generalizing about a group this diverse is folly in the first place. And taking their votes for granted turned out to be a strategic error for the Democrats (they still won the majority of Latino votes, but barely).

At the very least, the fact that historically blue (and majority Hispanic) counties like Starr in Texas (mostly Mexican-Americans) and Miami-Dade (mostly Cuban-Americans) in Florida turned red should put to rest two myths: on the left, the assumption that only white racists vote for Trump, and on the right, that there is a Democratic plot to increase immigration in order to win elections (if that is their master plan, it needs some tweaking).

Meanwhile, in Mexico, the return of the GOP and Trump 2.0 has been met with concern, but not panic (more on this below). The peso slid immediately after the election, then recovered, and slid again following Trump’s take-no-prisoners cabinet pick announcements, including Cuban-American Marco Rubio for Secretary of State.

Rubio, described as hawkish on foreign policy, has accused of López Obrador of handing Mexico over to drug cartels and he’s a vocal critic of Latin America’s leftist governments. For better or worse, it looks like the region will be a higher priority on the U.S. foreign policy radar moving ahead. As noted in an AP report:

“As the first Latino secretary of state, Rubio is expected to devote considerable attention to what has long been disparagingly referred to as Washington’s backyard.”

Cuba may well become the catalyst for a diplomatic spat between the U.S. and Mexico. According to former Secretary of Foreign Affairs Jorge Castañeda, the Rubio pick means “the most anti-Castro government in the U.S. since Kennedy and the most pro-Cuban one of Mexico since López Mateos” are going to coincide. The affinity between AMLO’s government and Miguel Díaz-Canel’s in Cuba is continuing under President Sheinbaum, whose administration helped alleviate the country’s recent energy crisis by sending barrels of Mexican oil for “humanitarian reasons.”

Sheinbaum has stuck to her script in response to Trump’s win: the relationship with the United States will be good, and the Mexican government will always defend Mexicans on the northern side of the border. She said she had a “cordial” congratulatory call with Trump. Her secretary of economy, Marcelo Ebrard, has also noted there are still economic opportunities for Mexico as the United States’ largest trade partner—while challenging Trump’s blanket tariff threats with “if you tax my exports, I’ll tax yours.” He’s also trying to get a meeting with Elon Musk to discuss a certain “gigafactory” project south of the border. Get in line, Ebrard.

In other news (yes, it’s still happening!) there was a shocking outbreak of violence in Querétaro, a state that up until now had mostly avoided the cartel turf wars. An attack on a bar in the capital city at around 9 p.m. on Nov. 9 left 10 people dead (seven men, three women) and 13 injured. Omar García Harfuch, national security secretary, said this is the result of a conflict between the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG) and the Santa Rosa de Lima cartel, which has also been blamed with the ongoing violence in the neighboring state of Guanajuato.

The Partido de Acción Nacional (PAN)—which happens to be in power in both Guanajuato and Querétaro—selected a new national party president, Jorge Romero, in an internal election held on Nov. 11. While outgoing president Marko Cortés will not be much missed, Romero seems to already have as many critics as Cortés did.

Sheinbaum slammed Romero in one of her mañaneras last week, alleging he’s the leader of the “real estate cartel” that has been under investigation in Mexico City for years in the PAN-run borough of Benito Juárez. Romero says none of these allegations can be proven, and that while he would “never raise [his] voice to a woman,” he will also not be “intimidated.” But criticisms of Romero don’t come only from Morena.

As Sheinbaum also pointed out, the country’s last PAN president, Felipe Calderón and his wife, federal deputy and one-time presidential candidate Margarita Zavala, have both accused Romero of corruption, exortion and manipulation of internal party elections.

Can Romero bring a revitalized narrative and strong agenda to the PAN after repeated electoral setbacks?

“Morena will not lift you out of poverty, they want you poor so you depend on them…In the PAN, we want a thriving middle class, we want young people who don’t just hold our their hands, but find or create jobs,” said Romero in an interview after his win. “Have we made mistakes? Of course. But that’s not just something panistas do, that’s human.”

Speaking of humans making mistakes, the story of an imposter psychiatrist (who appears to need psychiatric help) in Puebla catapulted into the national conversation last week. Marilyn Cote might have continued to get away with practicing psychiatry without a license indefinitely if she’d just kept things a bit more…modest.

However, Cote was very active on social media, and claimed she had degrees from Harvard, had worked for the FBI’s (fictional) behavioral analysis unit in Quantico, and had been the director of a mental disorders institute at the University of Oslo. She used creepy photo-shopped images of models (and herself) in her advertising.

This lawyer also offered a tantalizing seven-day “cure” for depression, “treating” patients and prescribing psychotropic medications without any medical license. Her social media accounts have since been shut down, and her practice suspended by Cofepris while Puebla’s health authorities investigate. Maybe she can go back to imaginary criminal profiling for the FBI.

The Trump tango

According to the analysts at the Economist Intelligence Unit, Mexico ranks highest on the “Trump Risk Index”—hardly a surprising finding, considering that the policies of Mexico’s northern neighbor on immigration, drug trafficking and trade always have a significant impact here.

Mexico’s economy has been highly dependent on U.S. economic performance since NAFTA was implemented, and its growth outlook can look bright or stormy depending on what’s in the forecast for the United States. In other words, Mexico would also have been very “exposed” to the policies of a Harris administration.

Trump’s first term was actually net beneficial to Mexico’s economy; the trade war with China has helped Mexico usurp the role of biggest exporter to the U.S. and drawn “nearshoring” interest from foreign companies. The reboot of NAFTA as the USMCA under Trump further cemented this booming trade relationship. These trends have continued and accelerated under the Biden administration, along with the rise of another pillar of Mexico’s economy: remittances from abroad. While this income sent home by Mexicans (mostly from the U.S.) has been steadily rising for decades, the numbers exploded starting in 2020, and are expected to reach their highest level yet in 2024. Remittances may start declining, however, if Trump’s sweeping deportation plan is enforced.

Trump 2.0 looks to challenge Mexico more than the first term on various fronts, starting with the renewed threat of tariffs, which Trump likes to use as a blunt negotiating instrument. On the campaign trail, he also said he would “renegotiate” the USMCA, but it is already coming up for review in 2026. Canadian officials have been grumbling about the treaty as well—Ontario’s premier has said the U.S. and Canada should negotiate a bilateral treaty and leave Mexico out, citing concerns about China using Mexico as a “back door” into North America.

Sheinbaum responded to questions about the idea of elbowing of Mexico out of the trade deal by saying “that proposal has no future” and reiterating her stance that the North American economies “complement” each other.

It’s possible the “three amigos” free trade era is fading, but the economic fallout would be painful. After all, Mexico is also a top importer of U.S. and Canadian goods, not just an exporter (Mexico was the biggest recipient of U.S. food and agricultural exports in FY 2024). Costs for consumer goods (from avocados to pickup trucks) would also increase significantly and could cause an uptick in inflation, which never boosts any politician’s prospects.

Meanwhile, Mexico’s economic indicators have wobbled in response to Trump’s return, but not tumbled. Inflation spiked in October, reversing its downward trend, but the Bank of Mexico went ahead with a 25 basis-point rate cut, as had been expected following another cut by the U.S. Federal Reserve. The peso slipped to its weakest position in over two years the day after the elecion, then recovered slightly before dipping again as low as 20.7 to the strengthening USD, following the announcement of Trump’s cabinet picks, including hardline former ICE director Tom Homan as border “czar.” Homan has promised to run “the biggest deportation operation this country has ever seen.”

Prior to the U.S. election, Mexicans seemed in good spirits about the country’s economy—consumer confidence reached its highest level ever recorded in October. Foreign direct investment (FDI) has had a strong year and unemployment remains low. But most GDP growth forecasts have been modest for 2025, though the Department of Treasury and Public Credit (SHCP) published a hopeful 2-3% growth estimate on Friday as part of its 2025 budget presented to Congress. Bank of Mexico deputy governor Jonathan Heath called the government’s economic expectations “pretty optimistic.”

What are the moves Sheinbaum can make to counter Trump’s?

Shoring up the “southern wall” to stymie migration north was one of the bargaining chips used by her predecessor, and making an overt effort to push back on Chinese investment could be another. Secretary of the Treasury Rogelio Ramírez de la O said Mexico needs to reduce its trade deficit with China in September and focus on increasing domestic production, and Ebrard has also said Mexico will “mobilize” to enhance North American interests.

Lawmaking, bending, breaking?

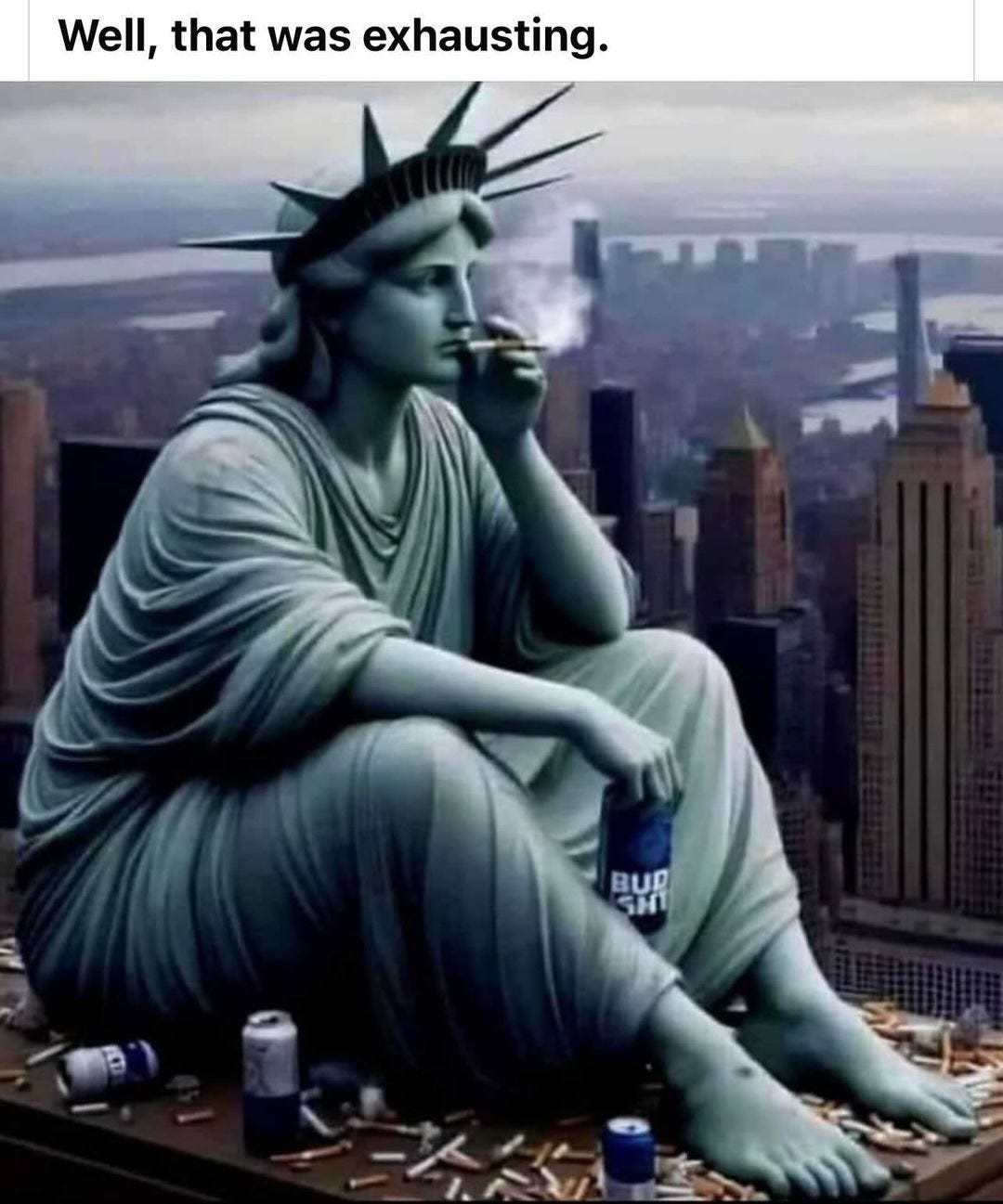

The war between Mexico’s branches of government has seen so many skirmishes in recent weeks that it’s tough to know where things stand. There are symbolic moments of victory for one side or the other that capture headlines, and then a frenzy of sparring in legalese. For noncombatants, watching the battle is often tedious, punctuated with cries of “the sky is falling.”

As the Morena-dominated Congress has continued full steam ahead with the package of constitutional reforms handed down by AMLO and blessed by Sheinbaum, the judiciary has revealed it is hardly exempt from pushing its own political agenda. Despite the strikes by federal court workers across the country, there have also been hundreds of lawsuits and injunctions filed against the judicial reform, which AMLO signed into law on Sept. 15.

On Oct. 30, there was dramatic news: eight of the 11 justices of the nation’s Supreme Court (SCJN) resigned. However, most of the resignations won’t take effect until Aug. 31, 2025 (one was already set to retire on Nov. 1 this year) and while their letters were submitted to protest Morena’s judicial reform, the resignations also coincided with an administrative deadline. The eight justices (including chief justice Norma Piña) had already said they wouldn’t participate in the 2025 judicial elections and if they had missed the Oct. 30 deadline, they wouldn’t have been entitled to receive their full retirement benefits.

On the same day the justices submitted their resignations, Congress passed a “constitutional supremacy” law in another fast-track legislative process—it was ratified in 17 state legislatures within 24 hours of passing in the Chamber of Deputies. The purpose of the reform, according to Morena and allied lawmakers, is to protect constitutional modifications from legal challenges, to ensure no one is “above” the Constitution. In short, the SCJN cannot rule that part of the Mexican Constitution is unconstitutional (though this was already the case, if not as explicitly as it is now).

As legal analyst Vanessa Romero Rocha (who is also on one of the electoral evaluation committees for judges) explained in a recent column:

“…The action of inconstitutionality—this is what the Constitution says, I didn’t come up with it—serves to reject laws that are contrary to the Constitution, not to put the ‘carta magna’ itself under a magnifying glass.”

There is no precedent for the courts to remove a constitutional reform from the Constitution, though the SCJN can consider the constitutionality of secondary laws, and of course, of any other bills passed in Congress but not elevated to the constitutional level (which requires a super-majority in Congress and the approval of a majority of the country’s state legislatures).

The “constitutional supremacy” reform was in part a response to a proposal from one of the justices of the Supreme Court, Juan Luis González Alcántara Carrancá, that would have invalidated key parts of the judicial reform (including direct election of federal district judges). In a Nov. 5 decision against the proposal, which was one vote short of a majority, Justice Alberto Pérez Dayán—who has been staunchly critical of Morena’s judicial reform, but also said previously the court “can’t rip pages out of the Constitution”—said that voting in favor of his colleague’s proposal would have meant “responding to one folly with another folly.”

For now, Morena and its allies in Congress are winning this war, and yes, judicial elections are coming—on June 1, 2025.

Mexico’s opaque judicial system meeting the noisy chaos of electoral politics is perhaps even more jarring than it would be in countries with a common law and accusatorial system (like the United States). Lawyers and judges argue cases mostly via written documents, though oral criminal trials have been gradually introduced nationwide following a 2008 constitutional reform. Perhaps it’s not surprising then that many judges, like Supreme Court justice Alfredo Gutiérrez Ortíz Mena, feel they are not fit for a position that depends on “popular support.”

The government has published a call for submissions from judges nationwide to participate in the elections, which promise to be a fierce logistical headache and may have low voter turnout. The National Electoral Institute (INE) presented a budget for the 2025 elections of 13.2 billion pesos, which Sheinbaum dismissed as excessive, noting that there will be no public funding for political parties in the judicial elections, as there is in executive and legislative elections.

Arturo Zaldívar, former SCJN chief justice and member of Sheinbaum’s team, told Milenio newspaper last week that there haven’t been many candidate applications thus far, even though the deadline is fast approaching (Nov. 24).

“This is a unique opportunity,” said Zaldívar. “For the first time in Mexico, lawyers can participate in and compete for a position as a federal judge, without needing connections, leverage or influence.”

Mexico goes to war against junk food (again)

Over 16 million Mexican children and adolescents, from age 5-19, are overweight or obese—one of the highest rates of childhood obesity in the world. A staggering 75% of Mexico’s population qualifies as overweight or obese (in 1980, only 7% was severely overweight). Mexico is the largest consumer of ultra-processed foods and drinks in Latin America, which (according to UNICEF) are the source of 40% of preschoolers’ caloric intake. Diabetes is the second-leading cause of death in Mexico.

“This is a problem we cannot ignore,” said Secretary of Education Mario Delgado at a press conference in October announcing the government’s plans to implement a school junk food ban. The law applies to all public and private schools, which have until March 2025 to implement the changes, or face fines.

According to government data from 2023-24, “comida chatarra” is sold at 98% of Mexican schools and sugary drinks at 95% of them. Only 2 out of 10 Mexican schools have free drinking water available on site.

The Mexican government has been waging a losing battle against processed foods for over a decade. Between 2010 and 2020, warning labels were added to food packaging for items that contain excess saturated fat, added sugars, calories or salt. In 2014, regulation was introduced to restrict sales of junk food in schools, but included a loophole: if the portions were small enough, the items could still be sold to students.

Some state-level bans have been introduced in recent years, and in December 2022, the national school junk food ban went into effect, pending regulations and guidelines from the Secretary of Public Education (SEP). These guidelines were finally published on Sept. 30, and prohibit the sale of food or drinks that have at least one warning label on or outside school grounds. The government plans to implement an educational campaign to help teachers, staff and parents adhere to the law, but how vendors near school grounds will be restricted isn’t clear.

Even if it is enforced, will this ban make a difference?

The processed foods and beverages available at any tiendita in the country offer a cheaper, more convenient option than many healthier foods and have become an integral part of the Mexican diet today. Many students bring processed foods and snacks with them from home.

While Sheinbaum’s government says it will put resources towards improved school infrastructure to address the lack of water fountains, for example, it’s hard not to be skeptical following years of SEP budget cuts (though in the government’s 2025 projected budget, there is a 1.6% increase in the education budget compared to 2024).

And then, there’s the fact that junk food is what kids (and adults) crave.

“I can make fruit and sandwiches; sell water, which I already do,” said one vendor, who has been selling snacks at her puesto outside a school in Mexico City for 34 years, in a recent report by El País: “But also, let me tell you: kids want something sweet. If they don’t buy it here, they will somewhere else.”

Thank you for reading and feel free to send me your suggestions, comments and questions at hola@themexpatriate.com. If you would like to support my work, please consider signing up for a paid subscription below.

Elephant in the room, indeed. As the Chinese say, "May you live in interesting times." Extensive overview of what's really going on, thank you.