Under the volcanoes

Mexico City turns 700 (again), plus the story of a contested historical artifact

“Welcome to the Valley of Anáhuac, where space and time converge!”

—Juan Villoro, Vértigo Horizontal

…and welcome to The Mexpatriate.

Mexico City is celebrating seven centuries since the founding of Tenochtitlan this month—but not for the first time.

The exact date of birth of the Mexica city is (unsurprisingly) slippery, although 1325 is the most widely accepted year. However, President López Obrador and Mayor Claudia Sheinbaum also honored the 700th anniversary of the megalopolis in 2021. Eminent archaeologist Eduardo Matos Moctezuma described this as a “manipulation” of history, to align the years of 1321, 1521 (the fall of Tenochtitlan) and 1821 (the year Mexico won independence). For AMLO, as the leader of a self-proclaimed “fourth transformation” in the history of Mexico, it seems this was an opportunity he couldn’t resist. On July 26, President Sheinbaum—who in March led a state funeral ceremony for Cuahutémoc, the last tlatoani of the Mexica—and Mayor Clara Brugada will lead this year’s commemoration ceremonies in the Zócalo.

In today’s edition, I take a breather from the news cycle to re-publish an essay I wrote in July 2022 about the prized “penacho de Moctezuma” and the potency of artifacts in historical myth-making.

While Mexico recovered over 14,000 artifacts from abroad during AMLO’s sexenio (compared to 1,300 during the term of Enrique Peña Nieto), and another 2,042 have been repatriated in the first six months of Sheinbaum’s term, this treasure remains out of Mexico’s reach—still housed in a Vienna museum where it has been on display since 1889.

The saga of the penacho of Moctezuma

Originally published on July 17, 2022

The July edition of Letras Libres magazine focuses on the theme “Legacies of Colonialism,” and includes an essay about the strikingly beautiful, and controversial, “penacho” (crest or headdress) of Moctezuma.

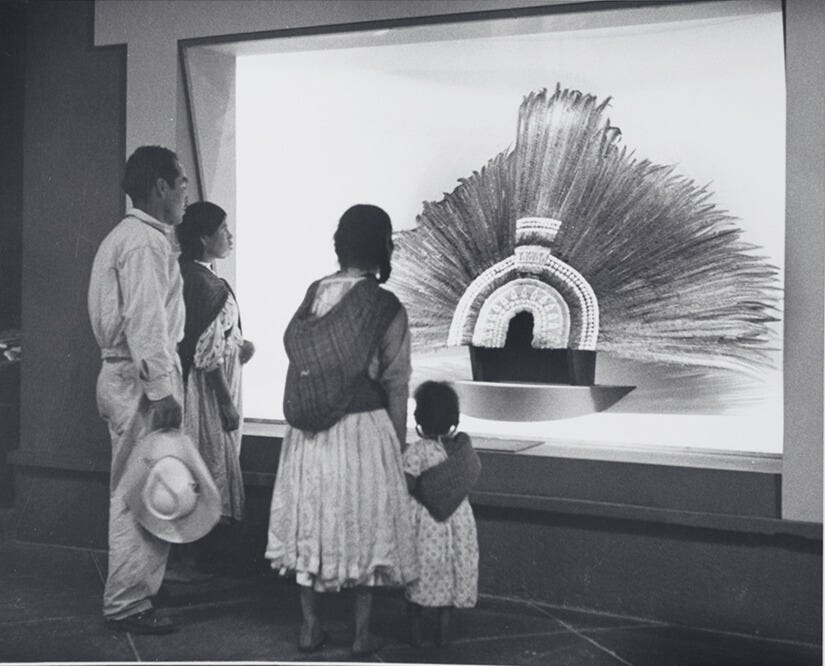

This historical artifact—a piece of “dynamic artisanal engineering” made from hundreds of feathers from four different bird species and 1,554 metallic adornments, most of them gold—has made the news several times this year alone, but has a much longer history of inspiring polemic debate. It is today part of the collection of the Weltmuseum Wien in Vienna, Austria, where it has been housed since the late 19th century. However, the penacho (or “quetzalapanecáyotl” in Náhuatl) has been in Europe far longer; it was first mentioned as part of the estate of Archduke Ferdinand II of Tyrol in 1596.

Several of Mexico’s presidents (including López Obrador) have requested the return of the artifact, and there was even a purported attempt by the Hapsburg Emperor of Mexico, Maximilian, to have the piece brought back to its land of origin. Austrian diplomats and curators have refused to lend or return the object to Mexico based on two arguments; first that it was a gift, second (and more convincingly), that it is too fragile to transport safely.

The Mexpatriate is a reader-supported publication. If you haven’t already, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription.

As is the case with many historical artifacts, what we know about the “headdress of Moctezuma” is shrouded in mystery, half-truths and speculation: to start, it may not have been used as a headdress, and it is unclear if it was used by Moctezuma. The piece may have been a ceremonial adornment that was given to Hernán Cortés by the tlatoani (ruler) of the Mexica, or it may have been stolen by the conquistador and sent, with other treasures, along with one of his missives to King Carlos V. We do know that many Mesoamerican cultures, including the Mexica, were masters of feather mosaic art (“plumaria”) and regarded feathers as important symbols in military and religious ceremonies.

“The feathers cannot be separated from the animal they came from, and thus the pairing of bird-feather defines their symbolic nature. The selection of feathers from certain birds, combined with other reflective materials, such as polished stones, pearls, shells and gold, were all part of the iconography and customs for each occasion,” explains the Mexican historian María Olvido Moreno Guzmán, who was part of the most recent joint Mexican-Austrian penacho restoration team.

The splendor of this ancient masterpiece, and the powerful symbolism it embodies, brings a swell of questions to mind: of myth versus history, nationalism versus rationalism and of the colonial legacy in the New World. After all, the “mystification of the continent began with Columbus himself.”

Does the modern state of Mexico, born in 1821—three hundred years after the fall of Tenochtitlan—have the right to inherit this treasure from the Mexica empire?

“To suggest that there is continuity from the owners of the ‘penacho’ in the 16th century to the contemporary Mexican state is to normalize a type of racial essentialism produced by not only blurring the ethnic and racial diversity of Mexico, but also marginalizing certain groups in this mix,” notes the essay in Letras Libres.

There is also the question of taking political advantage of the transcendent symbolism of this one object while ignoring so much more of the archaeological heritage of Mexico. As writer Rodrigo Flores Sánchez notes, “in Mexico we have not distinguished ourselves in respecting our natural, historical and cultural heritage.” The federal budget for culture has been slashed by this administration.

I saw a replica of the penacho on a visit last year to the “Grandeza de México” exhibit at the Museo Nacional de la Antropología in Mexico City. This piece was commissioned in 1938 by ex-President Abelardo Rodríguez and made by a feather mosaic artist (named Francisco Moctezuma) in conjunction with historians, archaeologists and biologists.

It is magnificent.

And yet, I confess to a tinge of disappointment when I saw the word “replica,” clouding my initial awe. Why? This penacho is no less iridescent in brilliance, no less a work of art, juxtaposing power and fragility. Perhaps our human yearning for connection with the past, for an intangible spirit long gone, sparks this desire for authenticity, to be physically in the presence of something real.

Which brings me to one more question: what do museums mean to us today? We are no less obsessed with curating curiosities (what else is Instagram?) but we can “see” and “collect” so much—everything we could imagine—in the internet emporium. What then is the value of visiting and gawking at art and artifacts IRL?

Maybe an answer lies within the centuries of European and Mexican dedication to the possession, preservation and display of this living fragment of a distant history.

Questions, criticism or tips? Email me: hola@themexpatriate.com. And if you enjoyed this newsletter, please share it.