Old news

Blasts from the past (and the future?) during the inter-campaign lull

Welcome to a Sunday edition of The Mexpatriate.

On Jan. 19, Mexico’s official “pre-campaign” period concluded, and the candidates pressed pause until March 1.

While Xóchitl Gálvez went abroad (from New York City to Madrid to Rome), Claudia Sheinbaum busied herself in Mexico (save a jaunt to the Vatican) and the president happily filled the political vacuum.

The discourse at the mañaneras in the early days of the month centered on two events from the past: allegations of drug cartel financing of President López Obrador’s 2006 presidential campaign, and the 1994 assassination of PRI presidential candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio. Both pull on threads implicating the major political parties and players in the past 30 years. And both have a performative quality, a sense we are being shown a spectacle meant to influence the national narrative as campaign season heats up.

And then, on Constitution Day (Feb. 5), López Obrador unveiled his latest suite of constitutional reforms, which includes 20 proposals ranging from the sweeping (pensions reform, judicial reform) to the specific (prohibitions of vapes and animal cruelty). The president doesn’t have enough support in Congress to pass his legislative gambit, most of which the opposition parties have already said they will reject. Is this little more than an electoral stunt, or a vision for Morena’s future? Stay tuned for my deep dive on the reform proposals in the coming weeks.

Before I dive in, I want to note that I have added a paid subscription option for this newsletter for the first time, though I have not yet put any content behind a paywall. If you value my work and want to support it, please consider a paid subscription. I send my heartfelt thanks to those of you who have already upgraded.

#Narcopresidente?

In the summer of 2006, Mexico held its second presidential election of the democratic transition—six years after the election that ended 71 years of PRI rule. The PAN candidate, Felipe Calderón of Michoacán, had been President Vicente Fox’s Secretary of Energy, and his main rival was Andrés Manuel López Obrador of the PRD, mayor of Mexico City from 2000 to 2005. AMLO lost to Calderón by 0.6% of the vote, the smallest margin in Mexican history, and the months between the election and Calderón’s swearing in were marked by mass protests.

Ten days after taking office, Calderón sent 6,500 troops to confront La Familia Michoacana cartel in his home state and officially launched Mexico’s drug war. Calderón’s term would also see increased cooperation with U.S. law enforcement and an influx of funds and training via the 2008 Mérida Initiative. By 2017, the U.S. had sent US $1.6 billion of “assistance” to Mexico under this agreement.

In 2008, DEA agents began investigating allegations from an informant that the Sinaloa Cartel, via infamous kingpin Édgar Valdez Villarreal, or “La Barbie” (now imprisoned in the U.S.) had funneled money to AMLO’s 2006 campaign. And on Jan. 30 this year, three separate publications (ProPublica, InsightCrime and DeutscheWelle) published reports on this cold case, which had been pursued further (including with a thwarted sting operation), but officially shelved by the U.S. Department of Justice in 2011. The reports do not include evidence to show AMLO’s direct knowledge of the alleged bribes.

Just this week, more allegations of AMLO’s ties to drug money made their way to a prominent media outlet: The New York Times. In their report, they mention far more recent U.S. government investigations into AMLO’s sons and other close associates after he took office in 2018—while a formal investigation was never pursued, sources claim millions of dollars changed hands. Like the other reports, the NYT article relies on unnamed sources about the investigation, which itself appeared to be constructed from various criminals’ statements.

“The investigators obtained the information while looking into the activities of drug cartels, and it was not clear how much of what the informants told them was independently confirmed.”

AMLO preemptively lashed out at the newspaper on Thursday morning, revealing in his morning press conference the request his communications office had received for comment on the story, even reading out the phone number of the paper’s Mexico bureau chief. The NYT quickly posted a response on X: “This is a troubling and unacceptable tactic for a world leader when threats against journalists are on the rise.”

Why is this all coming to light now?

If you’re AMLO, the answer is clear: the DEA is attempting to meddle in Mexico’s election. He described the reports on his 2006 campaign financing as “libel” and asked the U.S. government how it could allow such “immoral practices.” Even an ex-DEA director, Mike Vigil, described the reports as a “direct attack against AMLO.”

AMLO and the DEA haven’t had a cozy relationship, and in fact, as a former DEA agent quoted in the ProPublica article about the 2006 case says:

“Nobody was trying to influence the election,” one official familiar with the investigation said. “But there was always a fear that López Obrador might back away on the drug fight — that if this guy becomes president, he could shut us down.”

Since taking office in December 2018, López Obrador has led a striking retreat in the drug fight. His approach, which he summarized in the campaign slogan “Hugs, not bullets,” has concentrated on social programs to attack the sources of criminality, rather than confrontation with the criminals.

The DEA’s ability to operate in Mexico has been restricted during AMLO’s term, though its presence has generated controversy and scandal for far longer. Worth noting: Nicholas Palmeri, the regional DEA chief for Mexico and Central America, was removed from his post in early 2023 for misconduct (including vacations with lawyers who represent major organized crime leaders).

To Xóchitl Gálvez and the opposition coalition, these reports seem like a boon, a high-profile way to suggest that AMLO (and his party) are corrupt, and friends to drug traffickers. Gálvez posted a video to X on Feb. 1, in between meetings in New York City (including with the editorial board of The New York Times), in which she addressed AMLO, saying “it is painful that in the world they say Mexico has a #narcopresidente.” At the large “March for our Democracy” demonstrations held around Mexico last Sunday, some participants also took up the “narcopresidente” cry.

The trouble with this stance for the PAN-PRI-PRD alliance is that they have “una cola que les pisen” (a memorable Mexican phrase that literally means “a tail they can step on”): Calderón’s top cop and Secretary of Defense—a “crucial architect” of Mexico’s drug war—Genaro García Luna, was convicted in January 2023 in New York on drug trafficking charges, and receiving millions of dollars of bribes from the Sinaloa Cartel. Some of the same informants and criminals referenced in the trio of media reports testified at García Luna’s trial.

So, what’s the takeaway?

Campaign financing in Mexico is notoriously opaque, not only to hide the interests of organized crime, but also more mundane political graft. As AMLO showed a strong position in opinion polls in 2006, it’s unsurprising that people on his campaign would have been approached by the country’s most powerful organized crime group. Based on the evidence made public so far, it’s difficult to draw solid conclusions on what happened after that. The information on the 2018 accusations is also slippery.

What is clear is that the U.S. government has shown no interest in pursuing an investigation of AMLO; on Feb. 6, Mexico’s Secretary of Foreign Affairs Alicia Bárcena told the press that U.S. Homeland Security Advisor Liz Sherwood-Randall had confirmed that her government considers this a “closed case.”

And after Thursday’s brouhaha, a U.S. National Security Council spokesman responded to the more recent allegations, saying that “there is no investigation into President López Obrador.”

Echoes of 1994

In addition to holding the biggest election in its history this year, Mexico marks a number of historic 30-year anniversaries in 2024: uprisings, assassinations, elections, trade treaties.

The EZLN uprising anniversary has come and gone, but on March 23, three decades will have passed since the death of PRI presidential candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio—a murder that changed modern Mexico.

Political assassinations often beget conspiracy theories, and Mexico provides perfect conditions for them to thrive: a deep distrust of the government, a cynical outlook on politicians and a Byzantine approach to criminal investigations. The man tried and convicted of the crime, in jail since April 1994, is Mario Aburto. He confessed to murdering Colosio, though he also later said he was tortured by law enforcement. He was arrested at the scene, with a gun that matched the bullets fired at Colosio’s head and abdomen. His motive has never been clarified.

On Jan. 30, the FGR (Federal Prosecutor’s Office) made public their accusation against a former intelligence agent, Antonio Sánchez Ortega, of participation in the assassination as a “second shooter.” However, they couldn’t show sufficient evidence for a judge to issue a warrant. Sánchez, who was briefly arrested at the time of the assassination and released, reportedly no longer lives in Mexico.

The FGR also cast suspicion on another member of the defunct CISEN intelligence agency: Genaro García Luna. The prosecutors claim that García Luna was instrumental in the cover-up of Sánchez’s involvement.

Meanwhile, Aburto is due for release from prison soon, since his sentence was annulled by a federal court in October. Colosio’s son, Monterrey mayor Luis Donaldo Colosio Riojas (representing Movimiento Ciudadano), has asked that Aburto be pardoned by the president. AMLO has said that he can’t do it, because he doesn’t “want the investigation to stop.” Some say he’d like it to keep going until it reaches former president Carlos Salinas de Gortari himself.

In another development from earlier this month, media outlets reported that the investigation carried out last year by the FGR could not find enough evidence to charge anyone with the torture of Mario Aburto.

Will Aburto’s release be thwarted? Will the FGR make any more headway on their case against Sánchez? And will the revival of this case help distract attention from suspicions about corruption in AMLO’s administration?

Is age just a number in politics?

“What’s new is back.”

So says Jorge Álvarez Máynez (38), the recently anointed 2024 candidate of Movimiento Ciudadano (MC), which lost its first charismatic presidential aspirant back in November when Samuel García (36) returned to his governorship. García has been by Álvarez Máynez’s side, as has his wife Mariana Rodríguez (28), who is running her own campaign for mayor of Monterrey.

While MC is generally considered a center-left party, it seems they’re going all in on demographics over ideology: throwing out “old politics” and representing youth, who as García notes, “are the majority in this country.” Álvarez Máynez says he believes in “intergenerational justice,” which he describes as the principle that “one generation doesn’t have the right to compromise another.”

The two other candidates in the race are 60 (Gálvez) and 61 (Sheinbaum), and AMLO is 70 years old (more than Mariana and Samuel’s ages combined). Mexico’s current cabinet ranks among the oldest in the OECD (average age of 61), and the average age of a Mexican legislator is 50. They are still spring chickens compared to the “chronologically challenged” duo running for executive office up north, but certainly don’t reflect the Mexican population at large, where the median age is 29.

But what do young people care about in Mexico? Does MC genuinely resonate with younger voters compared to the parties represented by older candidates?

Crime is the top concern for Mexicans across age demographics, but it disproportionately affects younger Mexicans. Homicide was the leading cause of death for Mexicans aged 15-44 in 2022, with 70% of all murder victims in this age range (and of these, 86% were men). Interestingly, MC seems to be tracking to the right on these issues, with Máynez expressing some admiration for Nayib Bukele—who is a youthful 42—and his crackdown in El Salvador. Máynez has hammered old guard politicians for allowing civilian authorities to “have surrendered their responsibility” to guarantee public safety in the last three sexenios (presidential terms).

However, according to recent polling, young Mexicans are not so convinced. MC has always been the underdog in this race, but forgetting its low total showing for a moment, the January Mitofsky poll demonstrated that Claudia Sheinbaum’s strongest demographic is 18-30 year-olds (65%), and Álvarez Máynez has his weakest support in this demographic (1.9%), performing better in the 31-49 and 50-up categories. Xóchitl Gálvez also has more popularity in these brackets than among the youngsters.

“Cut off his head”

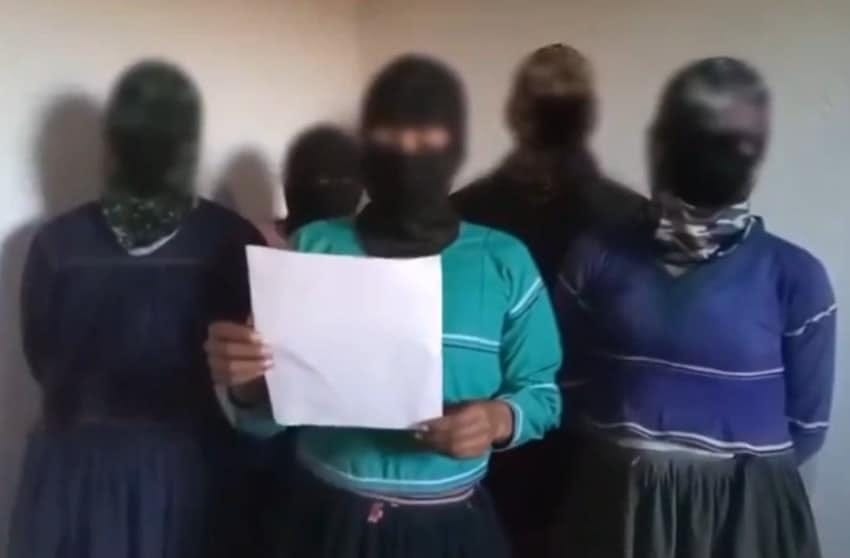

Five women, masked and dressed in traditional clothing, stand together; you can hear the person taking the video breathing throughout. One woman reads a letter—quite formal in style—addressed to one of Mexico’s most notorious drug lords, “El Mencho”, the elusive leader of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG). At one point, the woman asks “El Mencho” to intervene on their behalf to eliminate one of his subordinates, who has been tormenting their community: “cut off his head.”

This video started circulating on social media in the middle of January, and is yet another addition to the growing genre of citizen communications directed to cartels.

One of the more frequent examples is mothers searching for lost loved ones, who have pleaded with criminals to allow them to recover the bodies of those killed. Many of these mothers themselves have disappeared or been murdered.

A bishop in Guerrero stirred up the national conversation recently when he discussed meeting with criminal leaders in the Tierra Caliente region to attempt to negotiate a truce. While these negotiations failed, another priest reported that a “ceasefire” was apparently agreed upon last week between La Familia Michoacana and Los Tlacos after a particularly violent series of confrontations. In areas asphyxiated by organized crime, attempts at citizen mediation seem destined to increase.

Sandra Cuevas, mayor of Gotham

Cuevas is a politician to watch, even just for entertainment. She has veered from left(ish) to right (or into the DC Comics universe) as Mexico City’s Cuauhtémoc borough mayor. With her “diamond operations” to clean up the city streets, she drives a souped up all-terrain Batmobile through Roma and Condesa, and has made law and order the crux of her message.

She made a lot of noise with an inaugural event in January for her new political organization (Organization for the Family and Security of Mexico), which was held at the Arena México, site of Lucha Libre wrestling matches. You really should watch her entrance—it’s hard to ignore the Trump-ish vibe here. Her intention is to form a new party next year and run for president in 2030.

But Cuevas isn’t going to let this year’s elections go to waste. Last week she submitted her resignation as mayor in order to run for Senate, exchanging her Carolina Herrera pumps for neon orange sneakers in an acrobatic demonstration of “chapulineo”—Cuevas has decided to join Movimiento Ciudadano. A day after this announcement, MC Senator Patricia Mercado resigned her position as campaign spokesperson for Álvarez Máynez, saying she could no longer represent the party’s agenda.

Oh and speaking of garish sneakers, have you seen these “Never Surrender” high-tops?

Thank you for reading, and as always, send me your feedback by commenting below or sending an email to hola@themexpatriate.com.